Patrick Byrne and St Paul’s, Arran Quay, Dublin

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2007), Volume 15

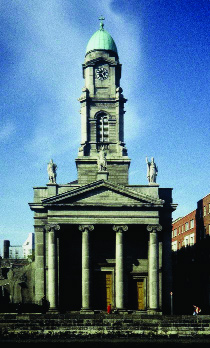

St Paul’s, Arran Quay-Byrne’s first church-building brief in 1835.

Following the Relief Act of 1793, the Catholics of Ireland began to erect churches of architectural pretension. In that year in Dublin work started on St Teresa’s, Clarendon Street. Outside Dublin three fine new churches were erected in the 1790s: Waterford Cathedral; St John’s, Cashel; and St Peter’s, Drogheda (since demolished). The first Catholic church in Dublin with serious architectural intentions was started in 1815 in Archbishop Thomas Troy’s parish of St Mary’s; it was opened in 1825 and is now popularly known as the Pro-Cathedral. In the same year Troy’s successor, Dr Daniel Murray, laid the foundation stone of the church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Whitefriar Street. A further series of fine Catholic churches were built in Dublin after Catholic Emancipation in 1829: St Nicholas of Myra, Francis Street (1829); St Francis Xavier, Gardiner Street (1829); St Andrew’s, Westland Row (1832); and Adam and Eve’s, Merchants’ Quay (1834). Several architects were involved in the design of these churches and none of them appears to have been a favourite with more than one of the commissioning patrons.

After 1835 this was to change with the design of St Paul’s, Arran Quay, by Patrick Byrne. Although Byrne was trained in the classical language of architecture, his versatility allowed him to adapt to the new Gothic style advocated by Pugin and asked for by some of his ecclesiastical patrons from the early 1840s. His other churches in Dublin are St Audoen’s, High Street (1841); St John the Baptist, Blackrock (1842); St James’s, James’s Street (1844); Our Lady of the Visitation, Fairview Strand (1847); St Pappin’s, Ballymun (1848); Our Lady of Refuge, Rathmines (1850); SS Alphonsus and Columba, Ballybrack, Co. Dublin (1854); St Assam’s, Raheny (1859); and the Three Patrons, Rathgar (1860). His reputation also extended outside the capital: he designed Catholic churches at Drangan, Co. Tipperary (1853), Arklow (1859) and Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow (1858). All his churches are still standing and, with the exception of St Pappin’s and St Assam’s, are still being used for their original purpose.

Patrick Byrne-vice-president of the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland from 1852 until his death in 1864.

Background

Little is known for certain of Byrne’s family background. C. P. Curran writes that he was probably a Dublin or a Wicklow man, judging from his name. He further speculates that he may have been the son of John Byrne, who took part in the architectural competition in 1769 for the building of the Royal Exchange. Patrick Raftery notes that Patrick Byrne made a fine watercolour of the interior of the Royal Exchange in 1834, thus strengthening the speculation that he had some connection with the eighteenth-century architect. He also suggests that there may have been some relationship with Edward Byrne, a rich Dublin merchant and chairman of the Catholic Committee. If true, this might help to explain his patronage by the Catholic clergy. His attendance at the Dublin Society School suggests either good connections or a talent that could not be ignored. Whatever his origins, his residence was in Blackrock, and the fact that he provided gratis all or a considerable portion of his architectural services in the design and building of the church of St John the Baptist is an indication of his attachment to the locality.

Byrne’s formal architectural education started in 1796 when, at the age of 13, he enrolled in the Dublin Society’s School of Architectural Drawing. There he was taught by Henry Aaron Baker (1753–1836), and thus was heir to the neo-classicism developed by James Gandon, who had Baker as a pupil, partner and successor. Work on the King’s Inns had started a year earlier, and his teacher must have been closely involved in the project, for which he took full responsibility after Gandon’s resignation in 1808. Byrne distinguished himself at the school by winning medals in 1797 and 1798.

Architectural career

Nothing is known of Byrne’s career from the time he left school until 1820. From 1820 until 1848 he worked for the Wide Street Commissioners, first as a measurer and then as an architect. This could mean that he was, in effect, city architect, but it could also mean that he was acting as a consultant when called upon. From 1848 to 1851 he was architect to the Royal Exchange. Little is known of his architectural work until his first known ecclesiastical commission for the new St Paul’s, when he was 52 years old. It is odd that no important work of architecture by him has been recorded before that date. Yet he can hardly have emerged fully formed as an architect at that stage of his life without having acquired considerable experience and established a reputation that would have enabled his patrons to trust him. If he was not practising architecture on his own account, he was almost certainly working as a partner or chief assistant with another architect; and if this premise can be accepted, the two most likely candidates are his teacher, Henry Aaron Baker, and Francis Johnston. Johnston died in 1829 before Byrne emerged in his own right as an architect, and Baker died in 1836. From 1796, when Byrne first became a student at the Dublin Society School, until 1835, when St Paul’s was started, the city had acquired several new public buildings, mostly by Francis Johnston (1760–1829): St George’s, Hardwicke Place, was begun in 1803 and finished in 1813; the Chapel Royal, Dublin Castle, was started in 1807, and the General Post Office was started in 1814. Also in this period the King’s Inns were finished by Johnston in 1816. From Johnston Byrne could have acquired his understanding of the Greek revival style, which he displayed with such competence in St Paul’s.

Byrne’s last ecclesiastical work was the church of the Three Patrons, Rathgar, which was started in 1860 when he was 77 years of age. He submitted proposals for a church in Donnybrook in 1860, but died before preparing detailed design drawings. It was not until 1861, with the design of St Saviour’s for the Dominicans by J. J. McCarthy, that Byrne’s reign in Dublin came to an end. In the 25 years since the building of St Paul’s he had made an important contribution to the architectural patrimony of Dublin. His architecture is also an expression of the social standing of a newly emerged Catholic middle class. Byrne enjoyed the esteem of his colleagues, especially in the later years of his life, when they elected him vice-president of the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland from 1854 (along with George Papworth), a post that he held until his death in 1864. This was the highest honour the architects could accord him; the position of president was, at this time, always held by someone from outside the profession. He was also accorded high esteem by his clients, and his talents were publicly acknowledged by the Very Revd William Meagher, who was the patron of two of his churches.

Our Lady of Refuge, Rathmines (1850)

His library

The contents of Byrne’s library provide some indication of his interests and education. It was auctioned by H. Lewis on 17 February 1864 and the following days (the catalogue is in the Royal Irish Academy). Not surprisingly, most of Byrne’s library consisted of books on architecture, and it indicates a man who was interested in architectural history, theory and criticism, as well as in the practical concerns of any architect. He also had novels, biographies, and books on travel, history, art, philosophy, science, music, mathematics and geography.

Like any practising architect in the nineteenth century, he had to build his own library of specialist books, not only to satisfy his general interest in architecture but also to inform himself on current developments. For example, most of his books on Gothic architecture were published (and probably bought) in the 1840s, when his patrons were being beguiled by Pugin and his followers. Some of the important architectural books in his library include John Ruskin’s Stones of Venice (London, 1851–3), his Seven lamps of architecture (London, 1849) and James Elmes’s Lectures on architecture (London, 1821), the latter regarded as an essential textbook for architectural students. He also had James Stuart and Nicholas Revett’s The antiquities of Athens (London, 4 vols, 1762–1816); these are folio size and the illustrations are clear and exact, and therefore useful to a practising architect.

He was well aware of French publications; his library included two copies of Paul Marie Letarouilly’s Édifices de Rome moderne (Paris, 1840) and Charles Nicholas Cochin and Jérôme-Charles Bellicard’s Observations sur les antiquités de la ville d’Herculaneum (Paris, 1757). Jean-Nicholas-Louis Durand is represented by three books: Essai sur l’histoire générale de l’a rchitecture (Liége, 1842), Recueil et parallèle des edifices en tout gênera, anciens et modernes (Brussels, n.d.), and Précis des leçons d’architecture données à l’Ecole royale polytechnique (Paris, 1823). He had Sir William Chambers’s A treatise on civil architecture (London, 1759) and James Gibbs’s A book of architecture (London, 1739).

Some of his books on Gothic architecture included Thomas Rickman’s An attempt to discriminate the styles of architecture in England (London, 1848), Frederick Paley’s A manual of Gothic architecture (London, 1846), Augustus Charles Pugin’s Examples of Gothic architecture (London, 1838), Augustus Welby Pugin’s The present state of ecclesiastical architecture in England (London, 1843) and Matthew Holbeche Bloxam’s The principles of Gothic ecclesiastical architecture (London, 1846). Most of Byrne’s work was ecclesiastical and his library contained several books that would have been useful for his practice, for example Richard Tress’s folio-size book Modern churches (London, 1841).

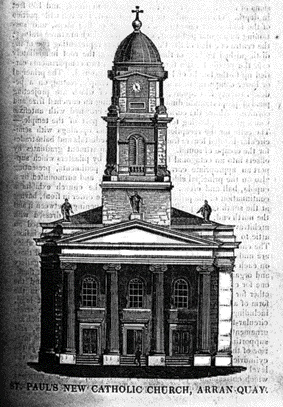

St Paul’s as illustrated in the Catholic Penny Journal, 10 January 1835. Unlike the church that was actually built, the columns are fluted and the front doors of equal size.

St Paul’s, Arran Quay

St Paul’s was Patrick Byrne’s first church, and it was the first Catholic church in Dublin to make a strong visual impact. Situated on the north side of the Liffey quays, it is the first prominent building visible from the western approach to the city. It assumes a place with two important eighteenth-century buildings further east along the quays, also on the north side and both expressing government authority: the Four Courts (1786) and the Custom House (1781), both by James Gandon.

The foundation stone was laid on St Patrick’s Day 1835 by the archbishop of Dublin, Dr Daniel Murray. The Catholic Penny Magazine published an engraving of the façade and a description of the church in its edition of 10 January 1835. No mention is made of the architect, but the article is signed ‘B’, possibly Patrick Byrne.

The Church of SS Mary and Peter, Arklow (1858).

The writer thought that the new church was ‘ likely to become one of the principal architectural ornaments of our city’. The portico of St Paul’s is built of granite, following the example of the Jesuit church of St Francis Xavier, Gardiner Street, which broke with the tradition of using a combination of Portland stone and granite that had been initiated in Dublin in the early eighteenth century with the building of the parliament house. The fine carving on the granite portico and façade is testimony to the skill of the stone-carvers who mastered such an unyielding material. Just over two years later the church was ready for use and was blessed by Dr Murray on 30 June (feast of St Paul) 1837. A sum of £600 was collected on the opening day.

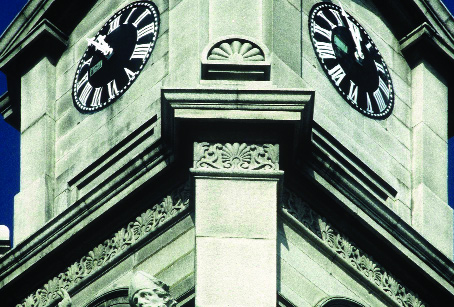

Although it only took two years to make the church ready for use, it took a further five years to finish the front. The portico (without the statues), bell-tower and cupola were finished and paid for by 1842. A considerable proportion of the building costs was expended on the front, compared with the provision of accommodation. Catholic church-builders were learning that the making of grand architectural statements was expensive. St Paul’s has a clock in the tower, with four faces. It is not clear whether the intention was to assert equality with the Protestant churches, which usually housed clocks, or to imply a public status for the building. Before the Reformation it was usual for churches to use bells to mark time. After the Reformation, a newly invented mechanism, the clock, began to be incorporated into bell-towers alongside the bells. Byrne may have unconsciously included the clock because it was part of this tradition, but it was more likely a deliberate decision to enhance the building’s status by assuming a responsibility to the public, which a clock implies.

In St Paul’s there are three entrances under the portico; the central door leads to the nave and the two side doors give direct access to two stairs, which lead to a very large balcony. The main entrance passes under the tower, through a draught lobby and into the nave. At the side to Lincoln Lane there were two entrances to the nave. The entrances were designed to direct members of the congregation to the part of the church best fitting their standing in society, and the separation of nave and balcony and a rail dividing the nave ensured that they were kept apart. To make the most of the site area available, the façade and the east side are aligned with the streets, which are not square to each other, resulting in a skewing of the main axis; this is obvious on the plan but hardly noticeable otherwise. Byrne was later to do the same in St James’s . Confidence in this solution is an indication of his knowledge of ancient Roman practice: the Romans would often bend the axis of a city gate, for example, to suit differing street alignments.

The first impression of the interior, as one’s eye is drawn to the altar, is the large wall painting in the apse; it depicts the conversion of St Paul, by F. S. Barff, behind a screen of giant Ionic columns. This idea was borrowed from St Mary’s, Moorfields (1817–20) in London, which was remarkable for the Baroque drama of its concealed lighting of a painting of the Crucifixion by Agostino Aglio (1777–1857) in the apse. St Mary’s, Moorfields, was illustrated in John Britton and Augustus Pugin’s Illustrations of public buildings in London (London, 1825 and 1828), and Byrne had a copy in his library. St Mary’s, which was an important Catholic church, was well known among clergy and architects interested in ecclesiastical architecture. The Catholic Penny Magazine (10 January 1835) noted that the lumière mystérieuse behind the altar was successfully used to the same effect in Les Invalides, St Roche and St Sulpice in Paris. It had been intended that the painting behind the altar of St Paul’s be a representation of the Crucifixion, just as in St Mary’s.

The nave is lit by ten round-headed windows (five on either side) between plain pilasters. Over the pilasters is an Ionic frieze and cornice, continuing around all sides of the interior. The Ionic theme is continued in the detailing of the ceiling, sanctuary and balcony. The ceiling is a shallow barrel vault divided into five compartments by transverse bands. (The shallow barrel-vaulted ceiling in the dining hall of the King’s Inns is also divided into five compartments.) Within each compartment are three rosettes framed with squares. In many respects the interior of St Paul’s owes something to Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Whitefriar Street, designed by George Papworth and started in 1825. The two churches have some features in common: the shallow barrel vault, the Greek detailing from the Erectheum, and the articulation of the external walls. Even the site restrictions determined that both churches should have narrow naves.

Corner of bell-tower with a decorative frieze copied from the Erechtheum, Athens;

pilaster capital at side of portico

onsole at the base of the bell-tower.

St Paul’s was to make more than a visual impression. It was not enough to have one bell; St Paul’s had a peal of six bells that were first rung on the Feast of All Saints in 1843. These joy-bells, as they were called, were popular with the citizens of Dublin, who came in their thousands to hear them rung for the first time. According to the Catholic Directory 1846, the bells were rung every Sunday and on special days ‘by select and judicious persons chosen and adapted for that important purpose’. They were made by James Sheridan, of the Eagle Foundry, Church Street. Sheridan was pleased with his work and placed an advertisement in the Catholic Directory describing the bells and the ‘great delight and satisfaction of the assembled thousands who came to witness the reviving sounds of Irish Christianity’. He praised the parish priest, Dr Yore, ‘whose patrician love for Ireland induced him to get them here, notwithstanding the allurements held out by the London bell-makers’.

The choice of the Greek Ionic order and the use of Greek ornamentation for St Paul’s are worth remarking on. Compared with England, and particularly Scotland, Ireland has few Greek revival buildings, and even in Ireland the Greek revival was accepted less in Dublin than it was in the provinces. Byrne’s architectural education, having come through the Chambers–Gandon–B aker tradition, was not calculated to incline him towards the Greek. Perhaps the impetus of the Greek revival provided by the Pro-Cathedral, and continued with St Andrew’s, was required to run its course with St Paul’s. The sturdy and masculine Doric seems fitting for the big churches in the archbishop’s parishes, St Mary’s and St Andrew’s. In St Paul’s the delicate Greek Ionic helps to convey a sense of the confidence that the Catholics of Dublin had by then become accustomed to feeling.

The drawing of the façade of St Paul’s shown in the Catholic Penny Magazine is slightly different to the façade as built. The drawing shows the three entrance doors at the same height, and three round-headed windows above the doors. This calm regularity accords with, for example, the neo-classicism of St-Phillipe-du-Roule, Paris, which has three entrance doors of equal height.

Interior view of St Paul’s, looking towards the altar.

(St-Phillipe-du-Roule was well known to contemporary architects and was used as the model for the Pro-Cathedral.) It also accords with the design of the Pro-Cathedral, where three doors of equal height were intended. The arrangement of doors and windows that Byrne intended for the façade of St Paul’s can be judged from the similar arrangements on the façades of Our Lady of Refuge, Rathmines, and SS Mary and Peter, Arklow, Co. Wicklow. Another departure from the design was the omission of the fluting from the columns. The fluting was clearly intended and would have completed the design. The façade of St Paul’s faces south and enjoys an open aspect over the River Liffey, and whenever the sun shines it looks its best. Byrne perfectly understood the subtle effects that his delicate bands of ornamentation, surfaces on different planes and angles, etc., would produce, especially in sunlight. The semi-ovoid dome was built as designed. Could the use of this type of dome be a subtle sign to distinguish the church as a Catholic one? Whether or not this is so, the semi-ovoid dome was later used on several Catholic churches.

Conclusion

Following the building of St Paul’s, Byrne enjoyed a successful career as an architect until his death on 10 January 1864, during which time he became almost solely responsible for creating in Dublin (with the help of his patrons, builders and craftsmen) the architecture that became part of the physical expression of the Catholic Church’s new-found strength in Ireland.

Brendan Grimes is a lecturer in the School of Architecture, Dublin Institute of Technology, Bolton Street.

Further reading:

C.P. Curran, ‘Patrick Byrne: architect’, Studies XXXIII (130) (June 1944).

E. McParland, ‘The Wide Streets Commissioners: their importance for Dublin architecture in the late 18th–early 19th century’, Irish Georgian Society Bulletin XV (1) (January–March 1972).

P. Raftery, ‘The last of the traditionalists: Patrick Byrne, 1783–1864’, Irish Georgian Society Bulletin VII (April–December 1964).