‘Parish pumps’—the role of the Church of Ireland in Cork City in early fire-fighting

Published in Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2020), Volume 28During the reign of King George I, a legal onus was placed on parishes in Ireland to provide fire-fighting equipment.

By Pat Poland

Just over 300 years ago, on 2 November 1719, the legal obligation of providing a ‘community fire service’ was laid on the Established Church, the last non-permissive piece of fire-fighting legislation in Ireland until the Fire Brigades Act 1940.

‘Fires are extinguished by the great number of admirable Engines, of which every Parish has one … so that no sooner does a fire break out but the house is surrounded with Engines, and a flood of water poured upon it, ’till the fire is, as it were, not extinguished only, but drowned.’

(Daniel Defoe on London fire-fighting, 1724)

‘… the Fire Engines belonging to the several Parishes, which are now kept in such wretched condition as not to be of the smallest use, when called forth, on any fire that happens, the Engine of St Paul’s Parish … only excepted …’

(Mayor Samuel Rowland on Cork fire-fighting, 1787)

Despite a catastrophic fire in 1622 which all but destroyed the city, over 90 years would pass before the first faltering steps were taken to provide some semblance of fire protection for Cork, and then only because of legislation enacted in London.

First effective legislation on fire-fighting

On 1 August 1714 Queen Anne, the last of the Stuart monarchs, died. Today she is remembered primarily for overseeing the Union of England and Scotland in 1707, thus creating the single sovereign state known as Great Britain; for bringing the unpopular and costly War of the Spanish Succession to a conclusion; and for having at least seventeen pregnancies, although none of her children would survive into adulthood. She is also, however, credited with being the monarch who took the first effective steps to stop the ravages of fire with her act of 1707 (6 Anne, cap.58), which introduced that famous institution—the ‘parish pump’. Initially the legislation was effective only in London, encompassing the area described as being ‘Within the weekly Bills of Mortality’. Not until 1715, during the reign of her successor, King George I, was a legal onus placed on parishes in Ireland to provide fire-fighting equipment (2 George I, cap.5).

The act applied to ‘the City of Dublin, or any other City or Town corporate within the Kingdom’ [of Ireland], but it was Statute No. 6 George I, cap.15, which received the royal assent on 2 November 1719, that copper-fastened fire legislation in this country. Henceforth it was mandatory for each parish to provide ‘one large engine and one small engine’ and to ‘keep and maintain one leather pipe and jacket as the same size as the plug or fire cock’. Churchwardens were directed to place fire-plugs at convenient distances on the water mains, ‘such plugs to be maintained and kept in repair at the expense of the parish’. Failure to implement the law could result in a fine of £10. The parishes in question were those of the Established Church, for by then Roman Catholic Ireland was suppressed in the deadly grip of the Penal Laws.

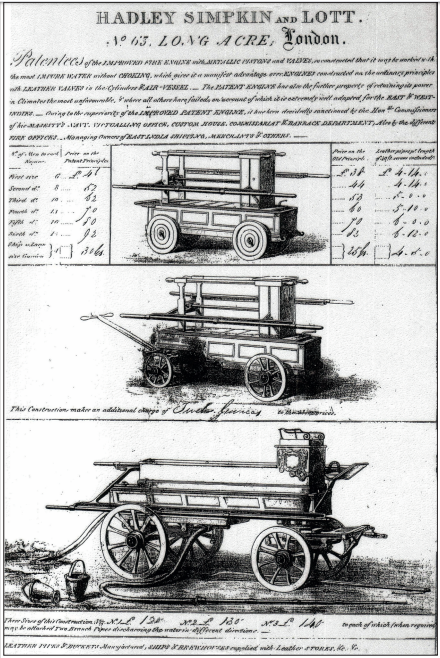

Above: Cigarette card depicting a parish fire-engine.

Local government

Above: A parish engine in operation at a fire, c. 1725. The bewigged gentleman directing the nozzle is standing on the air-vessel of the pump.

Each parish had its vestry, a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government of the parish, which originally met in the sacristy, or ‘vestry’, of a church. Over time, the church replaced the old manorial courts as the centre of rural administration. Vestry meetings attained a new significance; initiated solely for the administration of ecclesiastical matters, they gradually acquired greater responsibilities, such as Poor Law administration. The vestries became an early form of local government, supervising the maintenance of the parish infrastructure, taking responsibility for abandoned children (‘foundlings’), feeding the poor, burying the destitute (‘paupers’) and maintaining the parish pump (fire-engine). These civic services were financed by a local tax called the ‘parish cess’. All residents of a parish, irrespective of religious affiliation, had to contribute to the maintenance of the church by way of the so-called ‘tithes’, a rebarbative tax that was objectionable to Roman Catholics (who made up the vast majority of the population) in particular, and to Presbyterians, who gained nothing from it. The vestry minute-books of the Cork parishes have survived; some are held locally, some in the Representative Church Body Library in Dublin. All, without exception, contain many references to the upkeep and maintenance of the parish pumps.

Several new Protestant churches were erected in Cork during the early years of the eighteenth century and older ones replaced. All had their quota of fire equipment. In the ‘flat’ of the city these included Christ Church (a.k.a. Holy Trinity), St Peter’s and St Paul’s. The ‘south suburbs’ were served by fire-engines housed at St Fin Barre’s Cathedral and St Nicholas’s, while the north side was covered with pumps at St Anne’s, Shandon, and St Mary’s, Shandon.

Good on paper, useless in practice

Above: An advertisement for manual fire-pumps, c. 1800.

On paper, the parish pump system appeared beyond reproach, each neighbourhood church having a well-maintained fire appliance, ready to respond promptly to emergencies within its ‘area of operations’ or rushing to the assistance of contiguous parishes. The reality was somewhat different. By and large, the parochial system of fire protection was worthless. The pumps frequently stood rotting in churchyards, the beadle and other parish officials considering the attention that ought to have been paid to them to be the least important of their duties.

When fire broke out in stables off Camden Quay in January 1787, the only appliance of any use was the parish pump of St Paul’s under its ‘keeper’, Edward Sweeney. The incident prompted the mayor, Samuel Rowland, to place a hard-hitting notice in the newspaper:

‘The Mayor cannot avoid expressing his astonishment that in so extensive a trading city as this, a matter so obvious to the preservation of the Lives and Properties of all its inhabitants should be so shamefully neglected, and unattended to, and towards which he now wishes to excite their immediate serious attention, and that is the Fire Engines belonging to the several Parishes, which are now kept in such wretched condition as not to be of the smallest use, when called forth, on any fire that happens, the Engine of St Paul’s Parish, much to the credit of the Person to whose charge it has been committed, only excepted, and to the assistance of which alone may justly be attributed the happily suppressing on Thursday last a very dangerous Fire … which threatened destruction of the neighbourhood.’

He went on to implore the church authorities to immediately put ‘the Engines in compleate order … so as to render them of real use to the Publick’, and warned that:

‘A neglect after this Publick Notice must be considered as criminal in them, and they will be deemed by their fellow Citizens as highly accessory to any future losses they may individually or collectively sustain.’

By a strange oversight, the law that compelled engines to be procured and taken to fires did not provide for them to be actually worked upon arrival. As a result, the only object that their custodians had in view was to secure the sum of money allowed to the keeper of each pump that attended: 30 shillings to the first on the scene, twenty shillings for the second and ten shillings for the third and subsequent arrivals. As these were not inconsiderable amounts of money—30 shillings in 1719 approximates to €515 today (CPI inflation calculator)—there was often much bickering over who had arrived first, which was not always immediately obvious in the confusion and excitement of the moment. (The subsequent machinations to claim the premium award may have given rise to the expression ‘parish pump politics’.)

Sinecure

Above: Rocque’s 1759 map of Cork, showing the locations of fire-pumps: (1) City Courthouse, South Main Street; (2) St Fin Barre’s Cathedral; (3) St Nicholas’s, Cove Street; (4) Christ Church, South Main Street; (5) St Paul’s, Paul Street; (6) St Peter’s, North Main Street; (7) St Mary’s, Shandon; (8) St Anne’s, Shandon.

At a time when Goldsmith’s village preacher was ‘passing rich with forty pounds a year’, the (part-time) job of looking after the fire-pump was a highly desirable sinecure. Those entrusted with its upkeep possessed a lucrative sideline to their ordinary living. Typically, at the turn of the nineteenth century, the annual salary was about £5. This could be considerably enhanced where the keeper was also in charge of maintenance and repairs. In 1800 Thomas Bennett’s account for repairs to the St Fin Barre’s Cathedral engine stood at £28.10s.7d. At Easter 1816, St Mary’s, Shandon, owed Joseph Garde £103.14s.8d. for fire-pump expenses, plus another £100 ‘for necessary uses and repairs … to be assessed on the inhabitants and Ploughlands’: a total of a whopping £204, or the equivalent of some €22,890 today. In 1827 it was proposed that John McCarthy, the sexton at Christ Church, be retained as keeper at twenty guineas a year, but a counter-proposal recommended that Revd Alexander Kennedy should be given the post at £50 a year ‘as a remuneration or compliment for his long service as a Curate of the Parish’. This suggestion failed to impress the vestry, however, as it was considered that ‘such an appointment would be derogatory to him as a Clergyman, and it was resolved that the Sexton should be continued as Engine Keeper’. (The reverend gentleman’s thoughts on this arrangement are not recorded!)

Richard Newsham’s fire-pump

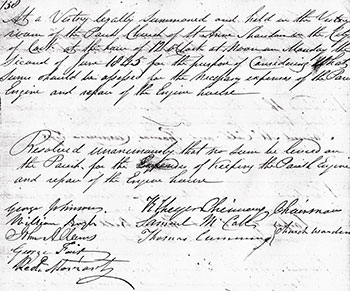

Above: The final entry (2 June 1845) in the vestry minute-book of the church of St Anne, Shandon, Cork, referring to parish fire-fighting.

So far as I am aware, no parish fire-engine has survived in Cork city. Two such examples are preserved in Dublin, however, and may be inspected at the Anglican church of St Werburgh. The larger of the two, though manufactured locally, is similar in design to those of the famous London fire-pump-maker Richard Newsham. Newsham had reintroduced the concept of having an air chamber so as to equalise the pressure output from the pump. In this way, the jet was projected in an uninterrupted continuous stream rather than in a pulsating fashion. For reasons that have never been fully explained, however, Newsham eschewed the use of delivery hose—widely used on the Continent—in favour of the old, discredited fixed-nozzle arrangement whereby the fire-fighter, standing on top of the machine, depended on the hit-and-miss capability of the so-called ‘long shot’. This tactic meant that the engine, to be effective, had to be brought up close to the building on fire, a manoeuvre sometimes fraught with danger. On occasion a burning building collapsed on engine and fire-fighter, burying both under the rubble.

Fire-pumps were built in six different sizes. Size No. 6—the largest—had a discharge capacity of some 773 litres (170 gallons) per minute. This marque cost £70, a substantial amount of money that would have bought a modest house. Christ Church is credited with having the largest and most powerful parish engine in Cork. These larger engines were not always advantageous in the spider’s web of lanes and narrow streets that were a feature of the city. When the tallow house of Mr Hawkes off South Main Street was severely damaged in a blaze on the night of 29 November 1800 and considerable time elapsed before water was brought to bear on the fire, the Hibernian Chronicle censured the authorities for permitting such hazardous industries in built-up areas, surrounded by domestic dwellings, where the fire-pumps were unable to approach. A similar situation prevailed—again off South Main Street—on the morning of Sunday 9 January 1814:

‘About 10am, a fire broke out in the rere of South Main-Street and Tuckey-Street, among some poor persons’ houses … the fire raged with considerable fury … and the engines were on the spot a long time before they could be of any service.’

Here again, the engines could not be manoeuvred to within their optimum working distance of the fire.

By the middle of the nineteenth century the parish fire-fighting system was largely discredited and irrelevant. As less reliance was placed on it, the well-established and more sophisticated fire brigades maintained by insurance companies were regarded as quasi-public institutions, with their fire-fighters holding a kind of public office (see ‘Ireland’s first 24/7 emergency fire service’, HI 19.1, Jan./Feb. 2011, pp 20–3). Among the last entries concerning fire suppression is that of St Anne’s, Shandon (of ‘Shandon Bells’ fame), whose minute-book records:

‘At a Vestry legally summoned and held in the Vestry room of the Parish Church of St Anne, Shandon, in the City of Cork at the hour of 12 o’clock at Noon on Monday the Second of June 1845 for the purpose of considering what Sum should be assessed for the necessary expenses of the Parish Engine and repair of the Engine House—Resolved unanimously, that no Sum be levied on the Parish for the Expense of keeping the Parish Engine and repair of the Engine House.’

From that summer of 1845 the church authorities would have far more pressing demands on the limited coffers of the ‘parish chest’. The horrific diseases and fevers associated with An Gorta Mór made no distinction when it came to crossing the invisible frontiers of politics, class and creed.

Pat Poland is author of The Old Brigade: the Rebel City’s firefighting story 1900–1950 (2018).

FURTHER READING

S. Ewen, Fighting fires (Hampshire, 2010).

T. Geraghty & T. Whitehead, The Dublin Fire Brigade: a history (Dublin, 2004).

J. Goudsblom, Fire and civilization (London, 1992).

P. Poland, For whom the bells tolled: a history of Cork fire services 1622–1900 (Dublin, 2010).