Pantomime

Published in Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2021), Volume 29By Laura Marriott

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were a golden age for English theatre, with writers such as Shakespeare and Marlowe drawing in the London crowds. Soon cities and towns outside the capital began to build their own theatres. Performances attracted a remarkably diverse group of people, from every socio-economic class. Theatre was a communal activity that included not just storytelling but also teaching and news-gathering, offering a rare chance for people from all of walks of society to meet and talk. Everyone from Elizabeth I, who patronised theatre companies and had plays written in her honour, to the groundlings who stood out in all weathers came to watch the magic of live theatre unfold in front of them. It was in this febrile atmosphere that visiting theatre groups brought commedia dell’arte to these shores.

Commedia dell’arte

Pantomime can be argued to have originated on the streets of sixteenth-century Italy as a form of street theatre called commedia dell’arte (‘comedy of the artists’). It consisted of strongly comedic performances that were very physical and often improvised and shaped to fit around different settings. Performers wore distinctive masks as a way to differentiate characters. The masks also served as a form of disguise, enabling actors to tell risqué or topical jokes as their characters and not as themselves. There were recurring stock characters and story-lines that the audience would expect to see. The most common featured two young lovers who were thwarted by their parents and their social status. Typically, the young lovers’ respective parents would refuse to let them marry, with the young woman’s parents usually wanting their daughter to marry a rich older man instead. By the end of the pantomime, the lovers would have found a way to either outwit their parents or defeat the unpleasant chosen suitor so that they could marry and live happily ever after. Some of the enjoyment of the performance comes from knowing that love will conquer all. Key elements of staging came into practice with commedia dell’arte and continue to this day. For example, the right side of the stage symbolised Heaven and the left side symbolised Hell. It is for this reason that even today the good fairy always enters from stage right and the villain of the piece always enters from stage left. Unlike today, this was a form of silent theatre.

A research project at the University of York has examined the history behind pantomime and delved into the vital role that John Rich played in its development. A dancer, acrobat and mime artist, he managed a theatre in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in the 1720s. When Rich combined a storyline from Ovid’s Metamorphoses with a harlequinade he helped to create a new kind of uniquely British theatre. A harlequinade was a visual experience in which the pantomime was dominated by clownish figures. It developed as a slapstick version of commedia dell’arte, which continued in popularity throughout the seventeenth century. Taking the form of an energetic chase, it featured many of the well-known stock characters, such as the clownish servants Harlequin and Columbine. This form of comedic non-speaking theatre relied heavily on visual spectacle, animals, props and cross-dressing. Critics, however, were not enamoured and poured scorn on pantomime.

Legendary eighteenth-century actor and Shakespearian David Garrick, manager of London’s Theatre Royal, saw how popular (and lucrative) pantomime was becoming despite the critics and, desirous not to lose his audience, he tried to come up with something crowd-pleasing. It is reported that he once said, ‘If they won’t come to Lear and Hamlet, I must give them Harlequin’. This commercial awareness served him well and he stunned audiences by creating what was probably the first speaking Harlequin.

Grimaldi and the ‘Great Dame’

At the end of the eighteenth century the clown Grimaldi, with his white face, painted-on red lips, piecrust collar and tendency to have custard pies thrown into his face, became immensely popular. Once again high and low culture merged, as Grimaldi, behind his clown mask, would have the freedom to incorporate politics and satire into the performance. Following on from this, in the nineteenth century the ‘Great Dame’ entered the scene and soon became the comedic focal point of pantomime. The Great Dame would be played by a man and would be recognisably male in that he would parody women rather than try to present himself as one. At the centre of a dysfunctional family, the Great Dame was a world-weary and haggard mother dealing with the woes of family life, facing adversity with a sense of riotous fun. It was through this character that pantomimes tackled serious subjects such as abandonment, poverty, lack of employment and absentee fathers in an indirect way. The absurdity of pantomime gave up on the idea of suspension of disbelief and instead invited the audience to take part in the lunacy.

The Victorians built on this by writing scripts based around fairy tales and incorporating songs and topical comedy imported from the hugely popular music-halls. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, Drury Lane theatre impresario Augustus Harris encouraged an inter-theatre competition designed to create the most lavish and spectacular stage productions each winter. He became known as the ‘father of modern pantomime’ and helped to facilitate the introduction of special guest stars into performances.

Dan Leno as Widow Twankey in Aladdin at the Drury Lane Theatre, 1896—an example of the ‘Great Dame’ who would be played by a man and would be recognisably male but who would parody women rather than try to present himself as one. (V&A Images)

Lifting of the Theatres Act

The Theatres Act, which had previously restricted the use of the spoken word in performance, was lifted in 1843. It was now possible for a theatre to produce a play with purely spoken language without a royal patent. This gave theatres and theatre-makers a great deal of artistic freedom. Along with the Great Dame came an increase in the use of puns, wordplay and double entendre. A hangover from the integration of elements of music-hall was the expectation of audience participation. Over time this has evolved from the singing of bawdy songs to a greater focus on children’s entertainment—but with a fair amount of double entendre thrown in for the adults.

Another side-effect of the lifting of the Theatres Act was the restricting of pantomime performances to the Christmas period. In the Regency period pantomime tended to be performed on 26 December and the weeks following, on Easter Monday and the weeks following, in early July and the summer months, and on Lord Mayor’s Day (9 November until 1959) and the weeks immediately following. Theatre managers feared that pantomime would damage ticket sales for other forms of theatre, eventually taking over British theatres. This would also have likely led to a reduction in script quality and eventually to audiences tiring of the genre. As a result, pantomime began to be staged only during the Christmas period. It quickly became a Christmas tradition, one that endures and flourishes to this day.

Continuously popular in Ireland

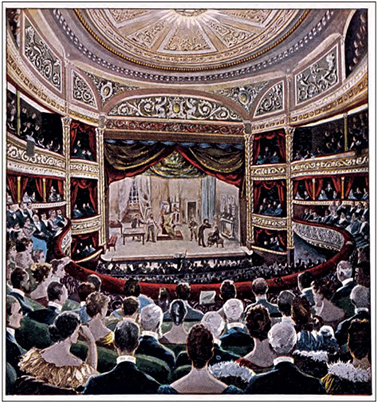

Above: ‘Souvenir of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the opening of the Gaiety Theatre’, Michael Gunn, 1896. The theatre as we know it today delivered its first pantomime in December 1873. (NLI)

Although seen as quintessentially British, pantomime has proven to be continuously popular in Ireland. This can best be illustrated by Dublin’s Gaiety Theatre dedicating time and space to pantomime each year. The theatre as we know it today delivered its first pantomime in December 1873—King Turko the Terrible or Harlequin Prince Amabel, The Three Magic Roses and Oberon, King of the Fairies, adapted by local man Edwin Hamilton. An Irish Times review stated that it was ‘worth going miles to see’. Although staged during the Christmas season, the pantomime was not tied into Christmas themes. Instead, as the title suggests, magic, the exotic and the integration of familiar characters took precedence.

Pantomime became as popular in Ireland as it was in Britain. This is reflected in the writings of James Joyce. In Ulysses, Leopold Bloom wanders the streets of Dublin and on occasion his mind is drawn to images from productions of Turko the Terrible and Sinbad the Sailor that he had seen at the Gaiety. In the chapter ‘Ithaca’, Bloom thinks about ‘the grand annual Christmas pantomime Sinbad the Sailor’, which had been a hit in the early 1890s, and the character of Turko the Terrible is bought up as a point of comparison at several points throughout the novel. Although the titles have changed significantly, the Gaiety is still known for its annual December pantomime.

Today, pantomime still includes the dramatic storytelling, stock characters and clear good-versus-evil that featured in commedia dell’arte. Over time, lengthy chase sequence, sing-alongs, magical props and fairy tales have been added to create a unique form of entertainment designed to appeal to children and adults alike. Pantomime is still associated with the Christmas season and is well known for its social satire and irreverent humour. It reflects both the development of theatre as a form of entertainment and the pantomime specifically that has moved from the streets of Italy to centre stage in Irish theatres.

Laura Marriott is a Dublin-based historian and theatre critic.

FURTHER READING

J. Chaffee & O. Crick, The Routledge Companion to Commedia dell’Arte (London, 2015).

P. Lathan, It’s Behind You!: the story of panto (Wahroonga, 2004).

R. O’Byrne, Dublin’s Gaiety Theatre: the Grand Old Lady of South King (Dublin, 2007).

D. Pickering, Encyclopedia of pantomime (Andover, 1993).