Pandemic cholera in Belfast, 1832

Published in Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2020), Volume 28A strong undercurrent of feeling against the medical establishment led to a steady refusal to go to hospital.

BY GILLIAN ALLMOND

Above: High Street, Belfast, in 1831, on the eve of the cholera outbreak. (NMNI)

In October 1830, alarming reports began to reach Belfast of an outbreak of ‘cholera morbus’ in Moscow. The Asiatic cholera, as it was also known, killed with dramatic suddenness, its cause was unknown and there was no effective treatment or cure. The disease had been endemic to the area along the Ganges for centuries, but in 1817 it began to spread beyond India, carried along trade routes by increased contact with Europeans. An exceptionally cold Russian winter in 1824 had prevented it from reaching Europe. Now that barrier had been breached, and the threat that cholera would reach British and Irish shores became ever more immediate. In late October 1831 the first case in England was reported in Sunderland, and the disease spread up the east coast of Scotland. By February 1832, Belfast Customs House had placed a precautionary quarantine on vessels arriving from the Clyde.

Belfast’s rapid expansion

The 1830s were a period of rapid expansion for Belfast, with a building boom funded by the profits from shipbuilding, engineering and textile industries, particularly linen. In 1831 the population of nearly 53,000 was almost three times what it had been 30 years before. Workers poured from the country into overcrowded courts, alleys and entries, hidden from sight although perhaps not from scent, behind the smart dwellings and premises facing onto the main thoroughfares. Responsibility for water supply, sewerage and refuse disposal was shifted ineffectually between town, landlords and tenants. In a compact town without, as yet, significant suburbs, the fates of both rich and poor were bound up together within a bustling square mile of ground.

Perceiving that it was only a matter of time before cholera reached Belfast, in September 1831 a temporary ‘board of health’—comprised of town officials, medical men and prominent clergy—was constituted and began to make preparations. The board ensured that lanes, courts and alleys were cleaned and ventilated and piles of refuse removed. They had the power to enter, cleanse and whitewash any house, to remove swine from houses, to burn bedding and to destroy clothing. A temporary cholera hospital was constructed at the rear of the Fever Hospital in Frederick Street, and the board rented a large building opposite as a ‘lazaretto’ to seclude those who had been exposed to the disease or who were showing symptoms.

Arrived from Scotland

As cholera became established in Scotland, the Irish poor flowed back home, their repatriation supported by the authorities in Glasgow. Boarding coal vessels in Portpatrick, where quarantine regulations did not apply, they alighted at Donaghadee and Bangor and walked into Belfast. The first cases of cholera in the town can all be linked to travellers from Scotland or contact between individuals. Bernard Murtagh, a cooper who had shared his lodgings with some Scottish visitors, was seized by vomiting and diarrhoea on the night of 28 February, the matter evacuated ‘being whitish and like … meal and water’, a characteristic sign of cholera. By the time he was seen by a doctor on the following morning Murtagh was ‘in a state of extreme weakness and collapse’. A trail of concerned medics visited with stimulants and emetics but Murtagh died about 7.30pm, nineteen hours after his first attack, the first case of cholera in Ireland. Over 20,000 deaths were to follow that year across Ireland.

The board of health saw to it that Murtagh’s bedding was burnt and the house was fumigated with chlorine gas. A guard was placed on the house for the next five days to prevent the inhabitants from leaving. Following this, the board of health began to make logistical plans for large numbers of cholera deaths. They approached the poorhouse and a price of 11s. was agreed for wooden coffins with iron handles made on site by the poorhouse carpenter.

The ‘blue death’

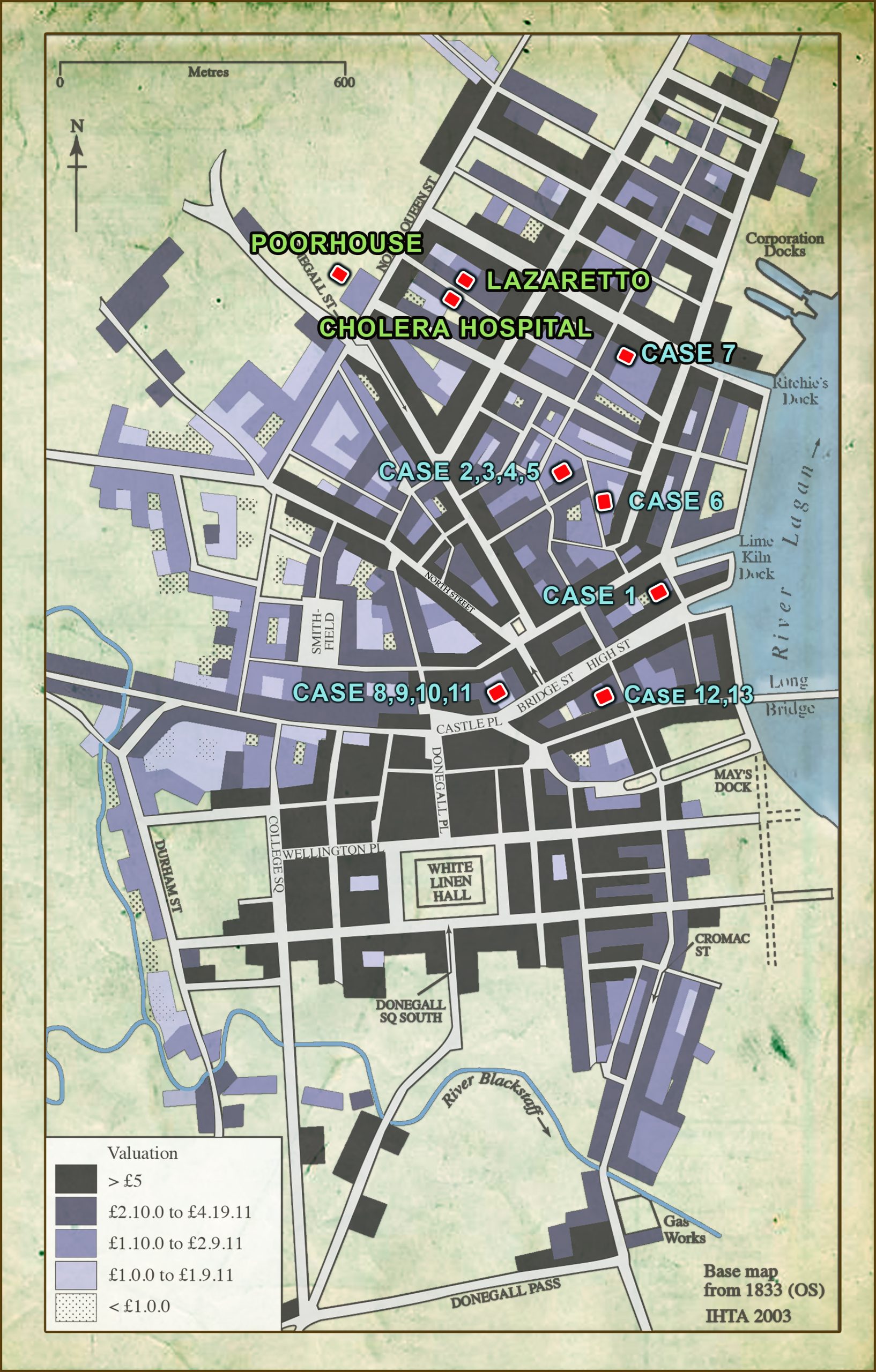

Above: Map of Belfast (1837), showing locations of first cases relative to building valuation. (IHTA/Tomás Ó Brogáin)

The next outbreak, carried by a cleaner from the lodging house where Murtagh died, was in Johnny’s Court, ‘a filthy confined place’ where the irregularly employed inhabitants were ‘destitute of any comfort’. There the disease killed several (Cases 2, 3, 4, 5), including ‘an athletic young man’ of 27 who had become for some hours before his death ‘a deep indigo blue’ (cholera was also called the ‘blue death’). A barber who had shaved the corpse of his brother for burial was the next victim (Case 6). The affected houses were cleaned and whitewashed, and the confined inhabitants were supplied with food and prevented from drinking whisky, ‘to which several were addicted’. These containment measures allowed ships to continue to sail from Belfast without being subject to quarantine.

Almost a month went by with no new cases and it seemed that Belfast might be spared. Then a man called Kirkpatrick who had travelled from Greenock came down with cholera in a street close to the hospital (Case 7). This case marked a shift in the public attitude to the medical authorities. Medical inspectors who visited Kirkpatrick were met by a crowd shouting ‘There go the poisoners’. In the evening, medical personnel from the board of health were surrounded by a furious crowd at his house and had to be rescued by police reinforcements. Three more families in entries off High Street (Cases 8–13) had family members taken to the lazaretto. Supporters generated another rowdy gathering that shouted ‘disgraceful imprecations’ against the doctors and the board of health.

Fear and mistrust of the medical establishment

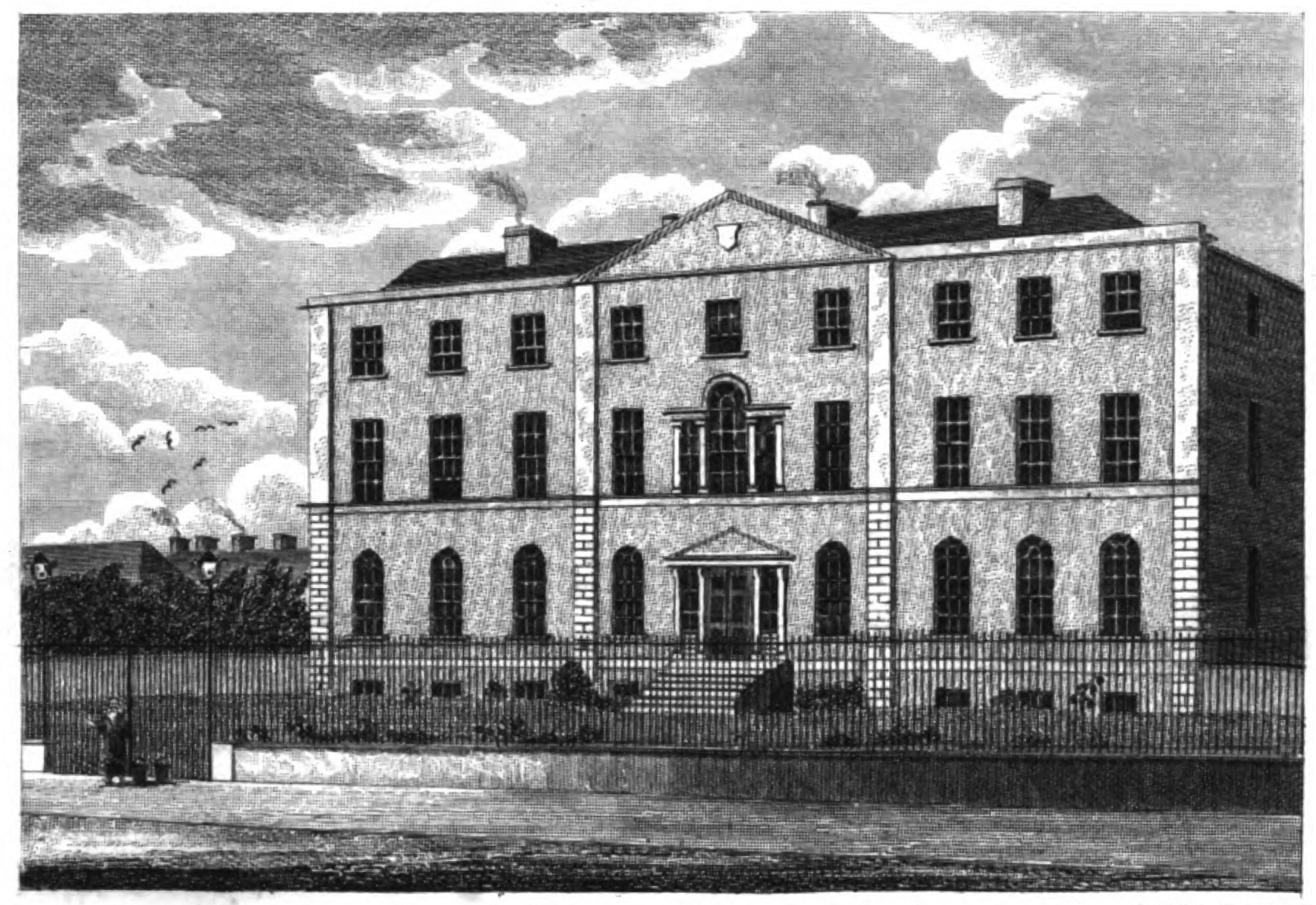

Above: Belfast Fever Hospital, Frederick Street. The sheds of the cholera hospital were constructed to the rear. (Archiseek)

There was a strong undercurrent of feeling against the cholera doctors, perhaps with some justification. Medical schools in Edinburgh and Glasgow, where most of Ulster’s doctors were trained, had created a steady demand for fresh corpses for dissection, and graveyards in Belfast were routinely guarded by watchmen with firearms and dogs. The export of corpses from Belfast to Scotland had taken place sporadically from at least the 1820s, and in the five months prior to the outbreak of cholera a total of four bodies had been discovered on the quay in Belfast, waiting in pine boxes for the boat to Glasgow. Two of these bodies were found to have been exhumed in Dromara churchyard; another could not be identified and was buried in Belfast. Three of the bodies were discovered to have been shipped by medical students.

The practice of ‘burking’ was even more disturbing; indeed, the suspicion that bodies for dissection were murder victims rather than ‘resurrected’ corpses hung over many cases of discovered bodies. Fresher in people’s minds at this period than the case of Ulstermen Burke and Hare was the notorious ‘burking’ case in Bethnal Green, where Thomas Williams and John Bishop drugged their victims, including young boys, and then drowned them head-first in a well. Bishop and Williams were tried and hanged in December 1831. Fear and mistrust of the medical establishment boiled over into riots, attacks on cholera hospitals and on cholera doctors themselves in some English cities. In Belfast, resistance to the efforts of doctors settled down into a steady refusal to go to hospital.

‘Came over the town like a shower’

Although it seemed early on that measures to contain the disease had been successful, in the middle of June the outbreak ‘came over the town like a shower, filling streets and lanes in almost every quarter with wailings and lamentations’. Dozens of new cases occurred almost simultaneously in widely separated parts of the town, and doctors who had concluded that the disease passed from person to person now began to favour theories of a poisonous miasma resulting from decomposition of animal or vegetable matter. It was not understood that cholera could spread through infected drinking water.

During June, July and August the disease raged across Belfast, with a peak of over 300 cases in one week in mid-July, and the hospital was filled to overflowing. The doctor in charge, Henry McCormac, praised the ‘courage and devotedness of the poor to each other’. They were not deterred by danger from watching beside their loved ones and ministering to them and, ‘when human care and solicitude were of no further avail, would kiss the distorted features and stretch the racked limbs before they should be consigned to their rest’. One military pensioner was nursed by his wife, who refused to leave his side until she herself was overtaken by the disease, saying, ‘We have now been 50 years together … and if I lost him I would not wish to live’.

Heated professional disputes arose over different approaches to the treatment of cholera. McCormac stuck by the treatment advocated by doctors in India, which was based on bleeding and the administering of calomel, a mercury derivative. Several of his colleagues at the time were openly critical. Dr William Maxwell Wilson, physician to the Fever Hospital, claimed that many patients left the cholera hospital with symptoms of mercury poisoning, such as salivation and necrotic jaw pain. Medical inspector Dr Hawthorne thought that blood-letting aggravated the loss of fluid experienced by cholera victims.

Around 60% of cholera patients were treated in their own homes by medical inspectors, often because they could not be persuaded to go to the hospital. William Murdoch, porter to a wine merchant in Donegall Street, was one of many such cases. Murdoch, who had given his wife ‘positive instructions to let him die in his own house’, was treated with arrowroot, laudanum and whisky enemas at home by Dr Thompson. Dr Hawthorne’s home treatment included copious drinks of whey, which appeared to be effective—‘the rapidity with which the drink was absorbed, and the sudden effect produced on the pulse by it, [was] very remarkable’. Sufferers who refused hospital treatment may have had some awareness that the mortality rate for patients at Belfast cholera hospital (24%) was much higher than for those who stayed at home (8%).

Burial

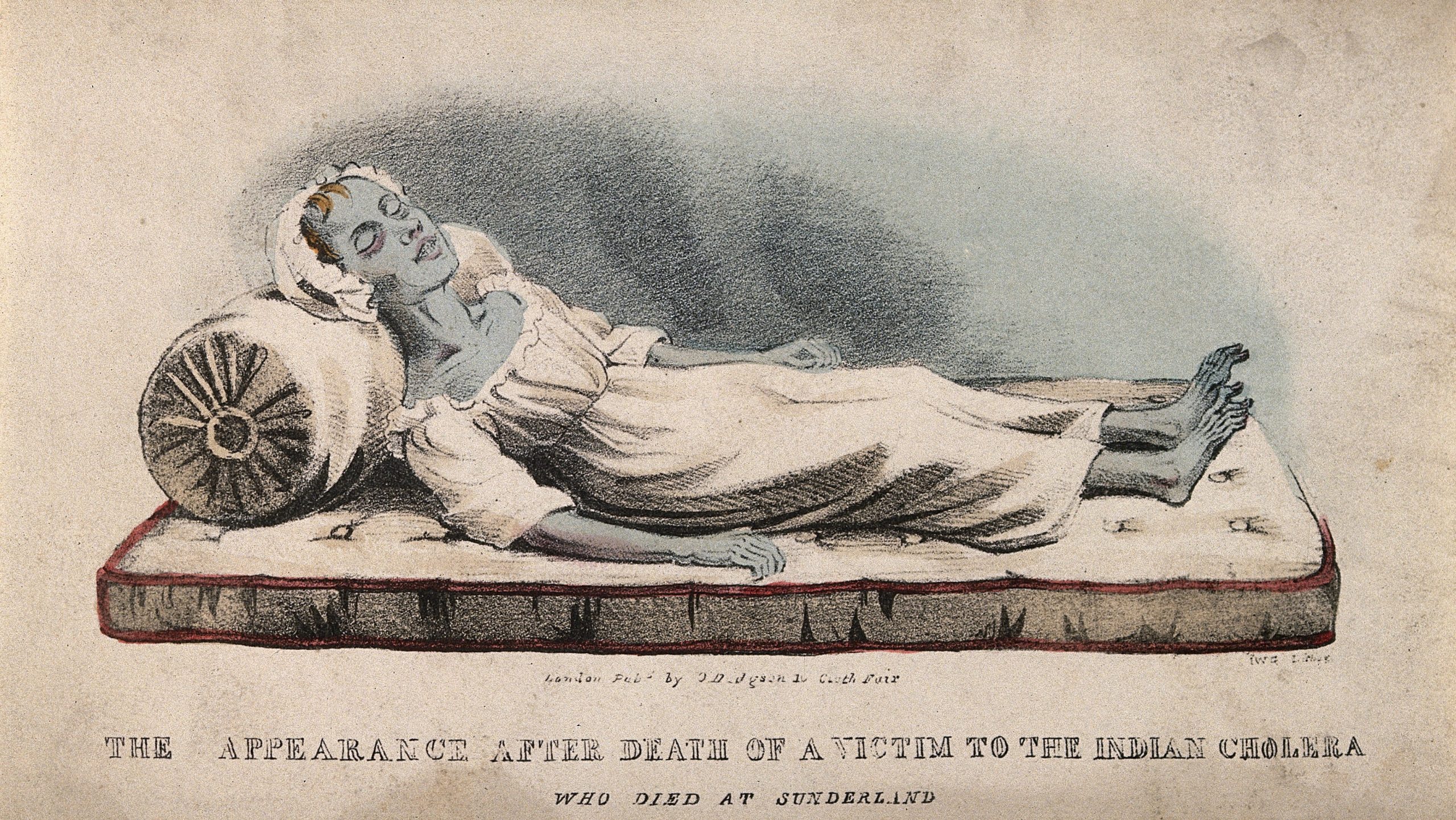

Above: ‘THE APPEARANCE AFTER DEATH OF A VICTIM OF THE INDIAN CHOLERA’. Note the distinctive blue colour. (Wellcome Collection)

The board of health instructed that cholera victims were not to be interred in the usual burying grounds and that all funerals were to take place within 24 hours, with wakes forbidden. Cholera deaths were given a ticket to the ‘dead house’ at the hospital and were supposed to be taken there immediately; however, the board was told on one occasion that if they attempted to remove the body of a woman who had died in Mill Street they would be resisted by force, and it appears that they backed off. Hundreds of cholera victims were buried in the town’s main Catholic burying ground at Friar’s Bush in a mass grave known as the ‘plaguey hill’, despite the board’s directives.

Visitors to the town were few in this period. An Edinburgh doctor, William Howison, felt a ‘disagreeable sensation’ almost every night he stayed in Belfast in August and was attacked with intestinal symptoms, which he felt to be ‘increased by imagination’. Howison was appalled by the ‘melancholy state of the streets, deserted by the inhabitants, most of the few who remained being in mourning, hearses passing continually by day and the noise of the wheels of the cholera carts rattling at a gallop … in the night time’.

The poor were considered particularly susceptible to the disease, which was partly blamed on their intemperance and their uncleanliness, ‘a most pestilent vice’. Cholera claimed several wealthy victims, however, most notably the banker William Tennent, a former United Irishman and reputedly the richest man in Belfast. William Howison described the dread that came over the inhabitants following Tennent’s death: ‘almost every wealthy individual of the place imagined his turn was to come next, and for days gave themselves up to gloom and despair’.

‘Merciful Providence’

By the end of September a ‘merciful Providence’ was being thanked for the disappearance of cholera from the town, as cases declined sharply. Apprehension died down, confidence began to return and there was ‘an appearance of bustle’ in the business parts of the town. A charity event was held for Sligo cholera widows and orphans, the highpoint of which was a ‘grand Terpsichore melange’ in which ballet dancers danced the Highland fling. The celebrations were premature, however, as the following week saw cases increasing sharply once again—26 deaths were recorded in the first week of October. Dr McCormac rushed to reassure an alarmed public that most fatalities had occurred in those ‘broken down by intemperance or enfeebled by want’ or who had failed to seek prompt medical assistance. Cholera cases almost immediately began to decline again and no more new cases were reported after the end of November. The board of health gave the town a clean bill of health and the cholera hospital was closed on 16 December.

The outbreak had lasted 46 weeks with 2,833 cases recorded, resulting in 418 deaths. Once the board of health was dissolved, however, public health concerns receded into the background. Cholera made several return visits to Belfast, with major outbreaks in 1848/9 and 1853/4. These caused a higher number of fatalities and had a more forceful impact on the middle classes. Ultimately the fight against cholera was to lead to a sanitary revolution in towns and cities throughout Britain and Ireland, following greater understanding of cause, prevention and treatment and the realisation that society as a whole would always be vulnerable to illness unless the poorest were free of disease.

Gillian Allmond is a Visiting Scholar in Historical Archaeology at Queen’s University, Belfast.

FURTHER READING

S. Johnson, The Ghost Map: a street, a city, an epidemic and the hidden power of urban networks (London, 2008).

G. Jones & E. Malcolm (eds), Medicine, disease and the state in Ireland 1650–1940 (Cork, 1999).