PAINT AND POLITICS—AN ‘UNHEALTHY INTERSECTION’

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2022), Volume 30The fate of Sir John Lavery’s ‘Irish history paintings’ exhibited at the Irish Race Congress in Paris in January 1922.

By Billy Shortall

On 28 January 1922, just two weeks after the Dáil acrimoniously ratified the Anglo-Irish Treaty, at a time when the new Irish state was unsure whether it had a viable future, the government organised and funded a major exhibition of Irish art in the then art capital of the world, Paris. The exhibition ran for a month and was timed to coincide with the week-long Irish Race Congress taking place in the city. The congress acted as a meeting place for Irish diaspora groups to organise themselves and discuss Irish affairs but its primary function was to present the grand narrative of Irish culture on the international stage. The congress, attended by pro- and anti-Treaty politicians, including three future presidents (Douglas Hyde, Seán T. O’Kelly and Eamon de Valera), was politically charged and one of the last times both sides met together before the outbreak of the Irish Civil War.

Irish culture was non-contentious and something that both sides could embrace. In an attempt to avoid politicising the event, Minister for Foreign Affairs George Gavan Duffy wrote to de Valera as leader of the anti-Treaty delegation to the congress, advising him that it was ‘mainly of a cultural and artistic character’; he thought that it would be wise ‘to send a delegation representing Ireland [that would] avoid party politics’ and would ‘represent fairly the two parties [sides] in An Dáil’. Eoin MacNeill led the official pro-Treaty delegation; both sides had five delegates. In fact, the congress was acrimonious and its outcomes were lost sight of in the ensuing breakdown of politics and the internecine Civil War.

SUCCESSFUL CULTURAL DISPLAY

The cultural display was more successful. In an evening of Irish theatre staged for attendees, two plays were performed, The Rising of the Moon by Lady Gregory and The Riders to the Sea by John Millington Synge. Both were performed by an amateur Irish drama group based in Paris and billed as the ‘Dramatic Section of the Irish Club of Paris’. Two concerts of Irish music featured a varied musical programme of well-known Irish ballads, hymns and airs played on a range of traditional Irish musical instruments—fiddle, flute and whistle. Significant contemporary pieces played on both nights were the ‘two string quartets, dedicated to the memory of Terence McSwiney’, composed by Irish-American composer Swan Hennessey. Well-known performers included Arthur Darley, Fay Sargent, Gerard Crofts and Terry O’Connor. Among a series of ten public lectures that offered a view of other aspects of Irish life and culture were Jack B. Yeats on Irish art, his brother William on literature, Douglas Hyde on the Irish language, Evelyn Gleeson on arts and crafts, J.J. Walsh on Irish sport and pastimes, and Darley on Irish music. The acme of the event, however, at almost half its total cost was the associated exhibition of Irish art. The 300 works exhibited displayed the breadth and quality of Irish contemporary art. Exhibits included modern works from the Society of Dublin Painters, more traditional works from the RHA, examples of stained glass, enamels and embroidery from the Arts and Crafts Society of Ireland, and the most fervently sought ‘modern Irish history paintings’, particularly those by John Lavery.

Discussions and correspondence on the exhibition between the organisers, including Minister for Art George Noble Plunkett, Arthur Griffith and de Valera, show that they expected a ‘propaganda value’ from the display of art and arts and crafts. Exhibitors included many now established in the Irish canon, such as Jack B. Yeats, Sarah Purser, Harry Clarke and Seán Keating. That they exhibited their best pieces is evidenced by the number displayed that ended up in public collections. The French state purchased Paul Henry’s A West of Ireland Village, now in the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. A painting of a uniquely Irish scene entering an important French collection authenticated Irish art, its recognition helping to achieve the ‘propaganda value’ sought by the congress organisers.

LAVERY’S ‘MODERN IRISH HISTORY PAINTINGS’

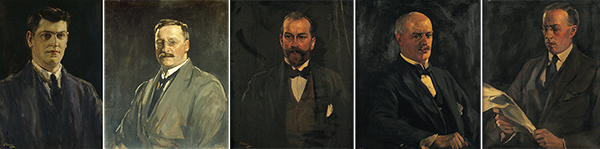

It was, however, the history paintings that were most important to the organisers. Art O’Brien, leader of the Sinn Féin organisation in London, communicated with Lavery to secure his ‘pictures of modern Irish history’, including ‘the portraits of President De Valera, the five [Treaty] Delegates, Archbishop Mannix, and the pictures of Terence McSwiney’s funeral, the Blessing of the Colours, etc.’, for exhibit. Lavery was enthusiastic in his response and also set about enlisting other artists to show their work. At one stage during discussions with the organisers in Paris he took offence when a preference was expressed for certain of his history paintings over his portraits of the Irish Treaty delegates, and he immediately withdrew all his entries. Cajoled, he reversed this decision and exhibited portraits of Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, George Gavan Duffy, E.J. Duggan, Robert Barton and Cardinal Logue, along with Funeral of Lord Mayor of Cork [Terence McSwiney] and Blessing of the Colours. McSwiney’s sister Mary’s attendance as one of de Valera’s representatives at the congress made the references to her brother in music and art more poignant.

Above: Sir John Lavery’s portraits of the Irish Treaty delegation—Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, George Gavan Duffy, E.J. Duggan and Robert Barton—exhibited at the Irish Race Congress. (Hugh Lane Gallery)

This was the first time that Lavery exhibited many of these portraits but it was not the last time that they caused a problem for the artist and politicians. In Paris these works were important; images of Irish politicians in statesmanlike poses showed a nation capable of self-government. The McSwiney funeral was an index to the atrocities perpetrated on Ireland by the British, and the Blessing of the Colours showed an Irish army officer kneeling before the Irish flag, being blessed by the archbishop of Dublin. The moment of consecrating the flag symbolised both the birth of a nation and the alliance of Church and State at this critical juncture in Ireland’s history.

LAVERY’S BEQUEST PROPOSAL TO THE IRISH FREE STATE

Above: The French state purchased one of the paintings exhibited—Paul Henry’s A West of Ireland Village (1921), authenticating Irish art and achieving the ‘propaganda value’ sought by the congress organisers. (Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris)

Lavery had also painted members of the British side to the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations, and in 1927 the artist proposed donating these and other works, along with portraits and paintings exhibited in Paris, to the Irish state. Over two years later, however, they had not been acquisitioned, and a 1929 Irish Times article about a separate presentation of 35 paintings by Lavery to ‘the new Belfast art gallery [Ulster Museum]’ intriguingly stated that ‘A similar, but bigger collection of Sir John Lavery’s works was offered to Dublin, but it seems that some difficulties have arisen in the Free State, and the pictures—which include a portrait of the signatories of the Anglo-Irish Treaty—are likely to be lost to Dublin’. Three paintings in the Belfast bequest were originally offered to Dublin and are now in the collection of the National Museums of Northern Ireland (the Logue portrait, a self-portrait and The Lady with the Green Coat).

Lavery approached President W.T. Cosgrave through Thomas Bodkin, director of the National Gallery of Ireland, with his bequest proposal in 1927. Bodkin was enthusiastic and wrote of Sir John and Lady Lavery’s ‘most generous project of presenting a large number of his pictures to Ireland’, works that Bodkin described as ‘of the greatest historical, as well as artistic, interest’. Although Lavery and Bodkin were both anxious, as the artist said, ‘to make the actual presentation soon’, they also suggested that some of the paintings should be stored and not exhibited immediately because a ‘few of [the pictures] would undoubtedly excite such feeling as might endanger [the paintings’ subjects] safety’. There were a number of agendas at play; Minister for Justice Kevin O’Higgins had been assassinated just weeks before the paintings were offered and Fianna Fáil were on the cusp of entering the Dáil, heightening tensions between both sides of the Civil War divide. Lavery’s portraits included both pro- and anti-Treatyites, such as de Valera and Griffith. Cosgrave, Bodkin and the artist all believed that many of the paintings of Irish politicians and English Treaty negotiators were political and had the potential to reignite Irish Civil War animosity among viewers and ‘should not for the present be publicity exhibited’.

Above: Lavery’s Earl of Birkenhead [F.E. Smith] (1923), one of the portraits deemed ‘controversial’ and which may have added to the delay in the acquisition of the ‘Lady Lavery Memorial Bequest’ until 1935. (Hugh Lane Gallery)

On investigation, it was discovered that the comment that upset Lavery was made by a member of the National Gallery board (most likely Chief Justice Hugh Kennedy, who had previously expressed his reservations)—‘that the gift would be an embarrassing one, based on the fact that it included portraits of persons who might be regarded as unpopular in this country e.g. “F.E Smith” (now Lord Birkenhead)’. This was the only painting identified as ‘controversial’, ‘dangerous’ or ‘embarrassing’. Birkenhead was notorious and universally disliked in Ireland for his staunch opposition to Irish nationalism, as a British negotiator and as British attorney general for his prosecution of Roger Casement; he appeared in two paintings—one, High Treason, of the Casement appeal, and a portrait. In reality, identifying Birkenhead as the only problem subject enabled the administration to avoid highlighting any division that still existed between each side of the Civil War. Portraits of both pro- and anti-Treatyites or paintings referencing the Civil War, such as Funeral of Michael Collins, Dublin 1922, were just as liable to incite political passions and ‘endanger safety’.

First offered in 1927, Lavery’s bequest was finally acquisitioned in 1935 as the ‘Lady Lavery Memorial Bequest’ in remembrance of his wife, who died the same year. Negotiating political anxieties, artistic temperament and rumour, it took eight years for the paintings to cross the ‘unhealthy intersection’ of art and politics to enter the state collection.

Billy Shortall is currently working on a TCD Long Room Hub project, available in early 2022, to virtually recreate the art exhibition and other events of the Irish Race Congress in Paris in January 1922.

Further reading

J. Lavery, The life of a painter (Boston, 1940).

K. McConkey, John Lavery: a painter and his world (Edinburgh, 2010).

S. McCoole, Passion and politics (Dublin, 2010).