Original Sins

Published in Issue 5 (September/October 2022), Reviews, Volume 30National Gallery of Ireland until 31 October 2022

By Donal Fallon

Above: Boreen. Michael, 1922—the pairing image of Collins depicts a country road, the kind where Collins met his end at Béal na Bláth.

The Shaw Room at the National Gallery of Ireland has a sense of opulence about it, complete with chandeliers and fine polished floors. In a corner, a bust of George Bernard Shaw watches the visitor, fitting in an institution that he thanked for ‘much of the only real education I ever got as a boy in Éire’. Shaw’s childhood fixation with the gallery would lead to the Shaw bequest, funds which were vital to allowing the gallery to grow its collections. In the words of curator Leah Benson, ‘the impact of his gift is evident when you walk through the rooms of the Gallery and see the influence it has had on the national art collection’. Entering the museum from Clare Street, Paolo Troubetzkoy’s impressive statue of Shaw is the first work of art a visitor encounters.

Now, Jacob Epstein’s less imposing bust of the playwright in the Shaw Room looks across on a display of work by Hughie O’Donoghue, Original Sins, which includes a depiction of General Michael Collins. On the passing of Collins, Shaw wrote to the family of the fallen leader, ‘how could a born soldier die better than at the victorious end of a good fight, falling to the shot of another Irishman—a damned fool, but all the same an Irishman who thought he was fighting for Ireland—”A Roman to Roman”?’

The historical influence shaping how Hughie O’Donoghue has interpreted Collins and others is not Roman, but rather Daniel Maclise’s The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife (c. 1854). The largest painting on display at the gallery, it remains a permanent fixture in the Shaw Room, while in the niches running along one side of the room we see hanging paintings by O’Donoghue, depicting historical figures from the melting pot of these islands in the centuries since the drama depicted by Maclise. As Seán Rainbird of the gallery notes, ‘as Ireland traverses the decade commemorating events of one hundred years ago, Hughie O’Donoghue presents six protagonists whose real and imagined histories shaped cultural, spiritual and political identities’.

On entering the space, Maclise’s work commands the attention of the visitor. Brendan Rooney of the gallery has written of it as a work that once divided opinion. To some in the past, it was a piece of ‘Victorian baroque trumpery’, and it journeyed around the gallery before finding its current home. It was only then, Rooney insists, ‘that the work assumed its iconic status, and came to be regarded, and embraced, as a profound and challenging historical statement’.

Maclise’s work, the marriage of two islands in some ways, inspired O’Donoghue to paint six figures—three men and three women—important to the history of these places. They are painted on industrial tarpaulin, but most importantly they are large enough in scale to not be lost beside Maclise’s towering presence. The figures depicted are the Irish Saint Deirbhile and King Wuffa of East Anglia, representing a time O’Donoghue has described as when ‘history and myth blur but nevertheless contribute to ideas of origin and identity’. In more direct homage to Maclise, we then see Aoife MacMurrough and William the Conqueror, while from the early twentieth century we encounter Michael Collins and the Suffragette martyr Emily Davison. These figures come from the histories of two intertwined places, but ‘each is also, irrespective of renown or period, the subject of myth’.

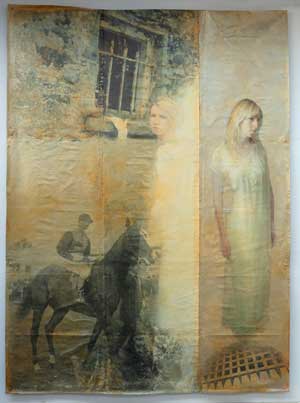

Above: The King’s Arrows and the King’s Horse. Emily, 2022—in the depiction of Emily Davison, we see a jockey upon a horse, a reference to the tragedy of her death at the 1913 Epsom Derby.

Commemoration has long fixated O’Donoghue, but so has identity. Born into a Mancunian Irish family in 1953, he has described his interest in memory as ‘very much to do with identity. What you remember tells you something about yourself.’ In many ways, as an interviewer noted in 2016, the artist has become the ‘living embodiment of one of the main themes of his work: the interwoven histories and circumstances that inform and shape identity’. Some relations fought in the First World War, others participated in the War of Independence.

Presenting six figures from the historical relationship between these islands, over such a period of centuries, raises an immediate issue. Collins and Davison are recognizable figures, a political leader and political martyr of the photographed age, but what of those symbolizing earlier times? O’Donoghue notes that ‘I used people who are close to me as models. This was a challenge but one that actually brought an exciting imperative to inventive imagination. I also used a well-known image of Collins, like a reference, appearing as what it is: a photograph.’

While the six figures may seem disparate in historical origin, the works are perhaps best understood as three pairs, which O’Donoghue states contain ‘plays on both similarities and differences going on between each work and its companion picture’. In the depiction of Emily Davison, entitled The King’s Arrows and the King’s Horse, we see a jockey upon a horse, a reference to the tragedy of her death at the 1913 Epsom Derby. Davison, The Suffragette newspaper proclaimed, ‘has proved that there are in the twentieth-century people who are willing to lay down their lives for an ideal’. The pairing image of Collins, Boreen, depicts a country road, the kind where Collins met his own end at Béal na Bláth.

Hughie O’Donoghue’s Original Sins is amongst the final contributions of the National Gallery of Ireland to the Decade of Centenaries. Recent months have also seen work by Günter Schöllkopf, honouring the anniversary of Joyce’s Ulysses, and a collection of work from Cumann na mBan revolutionary and cultural nationalist, Estella Solomons. Much of the Decade of Centenaries has been about inward reflection, and what it means for us to mark these significant anniversaries. O’Donoghue’s work reminds us that much of our past is the story of two islands, and two peoples.

Donal Fallon is a historian and the presenter of the Three Castles Burning podcast.