Opposing conscription

Published in Artefacts, Issue 2 (March/April 2018), Volume 26By Lar Joye

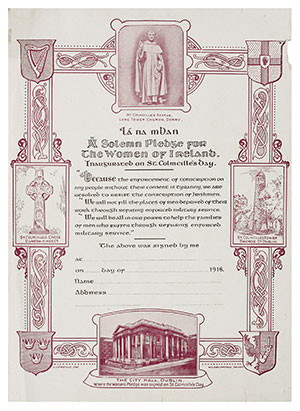

Above: ‘A Solemn Pledge for the Women of Ireland’—the signing of these special printed certificates was organised by Cumann na mBan on ‘Lá na mBan’, 9 June 1918. (NMI)

The British Army was to grow from 733,000 in 1914 to 8.5 million by 1918, which included the various armies of the British Empire and 1.5 million Indian soldiers. With a drop in recruitment in 1915, conscription was introduced in England, Wales and Scotland in January 1916 and proved to be very unpopular. Nevertheless, by the end of the war 35% of the British Army consisted of conscripts. On 18 April, when the bill imposing conscription in Ireland was passed, a meeting, arranged by Dublin’s lord mayor, Laurence O’Neill, was held in the Mansion House that would change Irish nationalist politics for ever. All the representatives at the meeting signed an anti-conscription declaration, including John Dillon, Redmond’s successor as leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, his colleague Joe Devlin, Michael Egan and Thomas Johnson of the Irish Labour Party, trade unionist William O’Brien, and Arthur Griffith and Éamon de Valera of Sinn Féin.

It was Éamon de Valera who drafted the document and the pledge, which stated: ‘Denying the right of the British Government to enforce compulsory service in this country, we pledge ourselves solemnly to one another to resist conscription by the most effective means at our disposal’. That evening de Valera led a group to meet the Irish bishops to win their support, which they did. The bishops then issued a manifesto, ordering that pledges be taken on the following Sunday (see p. 36). The pledge was signed throughout country on 21 April as well as during a ‘Lá na mBan’ on 9 June, with these special printed certificates organised by Cumann na mBan. Early in May de Valera appeared on the same platform as John Dillon at Ballaghaderreen, Co. Roscommon (see p. 34), again justifying Sinn Féin’s policies and further undermining the Irish Parliamentary Party’s position.

In the end, with the failure of the German offensive in June 1918 there was no need to impose conscription in Ireland. Nevertheless, the crisis and the resulting arrest of Éamon de Valera in response to the ‘German Plot’ on 16 May would ensure the continuing rise of Sinn Féin.

All these items can be seen at https://www.museum.ie/Historical-Collections.

Lar Joye is Heritage Officer, Dublin Port.