‘Old Skibbereen’: Fenian anthem or Famine lament?

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2016), Volume 24THE AUTHOR AND DERIVATION OF THE MOST WIDELY KNOWN SONG ABOUT IRELAND’S MOST MONUMENTAL CATASTROPHE HAVE REMAINED OBSCURE ALMOST SINCE ITS COMPOSITION

By Dan Milner

The first verse of the ballad ‘Old Skibbereen’ tells us that it was composed outside Ireland (‘Then why did you abandon it, the reason to me tell?’), and America stands as the most likely country of origin because the bulk of the Great Hunger emigrants sought refuge there. The Irish population of New York City rose from an estimated 70,000 in 1845 to an enumerated 133,730 in 1850. Though the aggregates were smaller in Boston, the ratios were strikingly similar. By 1850 the number of Irish immigrants in both municipalities amounted to 26% of the total.

The post-Famine period marked the apex of ballad-sheet publishing in the United States, and New York was its largest centre; there is no evidence, however, to show that ‘Skibbereen’ was published on broadsides, effectively ruling out the possibility that it was either composed for or distributed through street-song literature. Likewise, there is no evidence that it was sung in music halls, since it has yet to be found in a paper-covered songbook associated with popular song performance. Similarly, no nineteenth-century American sheet music has been discovered. ‘Skibbereen’ as we know it today is the product of a number of inputs that were combined over time to produce the song now commonly heard. Certain of these amalgamations were made in America, others in Ireland and Britain.

‘Poor Pat Must Emigrate’/‘The Irish Refugee’

One likely textual influence was a ballad known on both sides of the Atlantic under the titles ‘Poor Pat Must Emigrate’ and/or ‘The Irish Refugee’. New York’s foremost ballad publisher, Henry De Marsan, printed the song sometime between 1864 and 1878.

A common characteristic of English-language songs mentioning the Great Hunger is that they are rarely only about the catastrophe but more often about subsequent events or situations, using the 1845–52 period as an exemplar. In De Marsan’s ‘Poor Pat’ the narrator’s initial focus is on opposition to tenant-clearing evictions, but he also presents vivid, flashback images suggesting that the lyricist had viewed Famine horror firsthand:

I saw fathers, boys and girls,

With rosy cheeks and silken curls,

All a-missing and starving

For a mouthful of food to eat.

When they died in Skibbereen

No shrouds or coffins were to be seen:

But patiently reconciling themselves

To their desperate, horrid fate.

They were thrown in graves by wholesale

Which caused many an Irish heart to wail.

And caused many an Irish boy and girl

To be most glad to emigrate.

Like ‘Skibbereen’, in addition to eviction, other principal themes in ‘Poor Pat’ are the British government’s culpability in the huge loss of life and massive emigration, and the hope of nationhood for Ireland. Independence brought about by armed revolution is clearest in the final four lines of the New York text:

If ever again I see this land,

I hope it will be with a Fenian band;

So, God be with old Ireland!

Poor Pat must emigrate.

The song is likely to have originated in Ireland or Britain, judging by its wide geographical distribution throughout. An unmarked, but probably Irish, ballad sheet held at the Irish Traditional Music Archive in Dublin makes no mention of Fenians but ends instead with

But if ever again I reach this land

I hope I’ll be a different man

So God be with old Ireland,

For poor Pat must emigrate.

This change may have been prompted by concern about reprisal from government authorities, a conclusion supported by the absence of the print shop’s name and location. Proclaiming Fenian loyalty was of no concern in New York, where Irish nationalist rhetoric was uncensored, so De Marsan’s ‘Poor Pat Must Emigrate’ minces no words, proclaiming the overriding goal of return to Ireland to effect independence. In so doing, it is an important cultural marker because it asserts the determination of the Catholic Irish in the United States to elevate themselves according to their own model—one that included a politically autonomous national homeland.

‘Skibbereen’ is akin to ‘Poor Pat’—a definite resonance between the two suggests that the former received inspiration from the charismatic broadside. This similarity is evident in glimpses of eviction and starvation horror scenes, and especially in the eighth verse of ‘Poor Pat’, which concludes:

But I stood up with heart and hand,

And sold my little spot of land:

That is the reason why I left,

And had to emigrate.

A close match of these last words reverberates as many as three times in all sung renditions of ‘Skibbereen’ in variations of ‘that’s the very reason why I left old Skibbereen’. All versions urge armed hostility against the British government in revenge for the Great Hunger and subsequent tenant evictions, inherently regarding them as genocide and nullifying any possibility of further political union, but ‘Skibbereen’ goes further than ‘Poor Pat’ by calling for unending, intergenerational warfare until independence is achieved:

O! Father, Father, when the day for vengeance we will call, —

When Irishmen o’er field and fen shall rally one and all, —

I’ll be the man to lead the van beneath the flag of green,

While loud on high we’ll raise the cry — Revenge for Skibbereen!

Above: An Irish eviction (1850) by Frederick Goodall. All versions of ‘Old Skibbereen’ urge armed hostility against the British government in revenge for the Great Hunger and subsequent tenant evictions. (Leicester Museum & Art Gallery)

Lyricist identified

In 2003, researcher-librarian John McLoughlin came close to solving the question of composition: ‘The song’s author is unknown but it almost certainly originated in East Coast America and was probably written by a radical ex-patriot such as O’Donovan Rossa’. In 2012 a folk-song enthusiast group was able to identify the lyricist as Patrick Carpenter through an entry in O’Donoghue’s The poets of Ireland, which states that Carpenter was represented by a song named ‘Old Skibbereen’ in The Irish singer’s own book. Carpenter is also mentioned as ‘a native of Skibbereen, Co. Cork … [who] went to America many years ago’ and wrote poems for The Pilot (Boston) and Irish World (New York) newspapers in the 1870s. Handsomely bound with gilt edges for bookcase display, The Irish singer’s own book is in fact a compilation of three earlier collections, one of which, The wearing of the green song book, was published in Boston in 1869, with pages 208–10 bearing what may be the ballad’s first-ever print appearance. The tune specified is shocking to modern sensibility, however, for it is not the slow, woeful, minor-scale melody that has been associated with the song lyric through living memory but the strident, major-scale, martial tune ‘The Wearing of the Green’. Looking at the opening stanzas of both songs, one cannot help but notice that each starts with a question and that Carpenter’s lyric scans to the A-part of the melody every bit as well as Dion Boucicault’s ‘The Wearing of the Green’, substantiating the latter as a second influence and proving that what in living memory has been regarded as a Famine lament was actually created as a Fenian anthem.

Following its publication, ‘Old Skibbereen’ appears to have been distributed in the United States exclusively through nationalist circles and did not achieve wide popularity among Irish-Americans. In 1873 it was included in a ‘dime songster’, The favorite ‘Irish Sunburst’ songster, No. 3, published in New York by Robert M. De Witt (facsimile on pp 22–3). Then, remarkably, just two years later—on 4 December 1875—‘Skibbereen’ was printed on a ballad sheet at the Poet’s Box in Glasgow, its lyric unattributed and compressed from eight to seven verses, its currency described as ‘very popular’ and its tune cited as ‘original’. A possible explanation for these discrepancies is that the song arrived at the broadside publisher orally, without attribution to author, and that the well-known, major-scale ‘Wearing of the Green’ tune had already been disassociated, probably because it was regarded as unsuitable for a song that dealt so intimately, so gravely, with the Great Hunger—but there is no clue whatsoever as to the nature of the new ‘original’ melody. Abruptly, less than a decade after composition, Carpenter’s ‘Old Skibbereen’ had become an ‘anonymous’ folk song already absorbed into Irish song tradition.

Forty years further on and only one year before the Easter Rising in Dublin, Herbert Hughes included ‘Skibbereen’ in the second volume of his Irish country songs, noting that he had collected it in County Tyrone. Hughes, a sophisticated musician-composer trained at the Royal College of Music in London, is credited as the editor and arranger of the book, implying that he reserved licence to alter either or both text and tune. The minor-scale melody that he provides bears some relation to, but is not identical to, the one typically heard today. Neither is it fully convincing as a traditional air. This suggests the possibility that Hughes’s tune is his ‘improvement’ of the one now common. Folk-song collector Sam Henry received the melody from an unidentified singer who used it as the air for ‘The Banks of the Nile’, publishing it on 2 June 1928 in his ‘Songs of the People’ newspaper column in the Northern Constitution.

While ‘Skibbereen’ was spreading in Ireland, it appears to have lain dormant in America. Indications of this are its absence from widely owned Irish songbooks. But it reappeared in America in the early 1920s on phonograph recordings made by tenors Shaun O’Farrell and George O’Brien, confirming that immigrants from Ireland brought ‘Skibbereen’ back to its American homeland.

Above: Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa (with family) in 1905. In 2003 researcher-librarian John McLoughlin speculated that he may have been the lyricist. (NLI)

Fenian anthem or Famine lament?

Still left is the question of whether ‘Skibbereen’ is ultimately a Fenian anthem or a Famine lament. The answer is a matter of historical perspective. At first, ‘Skibbereen’ was an Irish-American nationalist anthem, though not a popular one, because it was infrequently published during the nineteenth century. By the time Hughes had collected and printed it in 1915, ‘Skibbereen’ was already incorporated into popular tradition in Ireland. The stimulus that set the metamorphosis in motion towards its adoption as the best-known song of the Great Hunger was its being joined with a sympathetic, slow, minor-scale melody that better complemented Carpenter’s words, which are actually literary rather than lyrical and not a good match for the fast, soaring ‘Wearing of the Green’ melody. The words could now be heard, admired and considered.

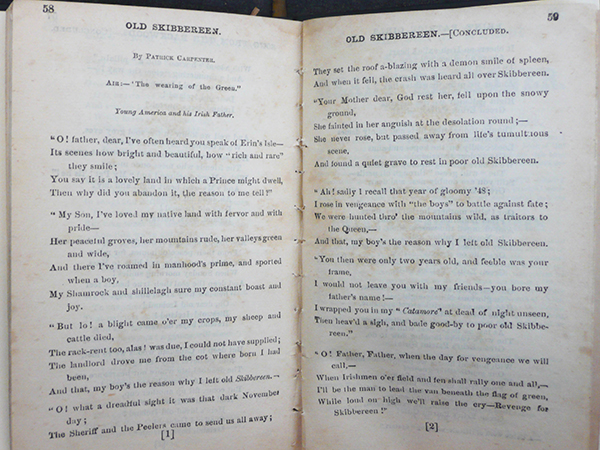

Above: Pages 58 and 59 of The favorite ‘Irish Sunburst’ songster, No. 3, printed by Robert M. De Witt, 33 Rose Street, New York, in 1873, with the same lyrics, also attributed to Patrick Carpenter, that appeared in The wearing of the green song book in Boston in 1869.

The basis for understanding ‘Skibbereen’s’ migration from America to Ireland and its reintroduction to the United States lies in the nature of traditional song. Unlike modern popular culture, which emphasises individualism, copyright, commerciality, abrupt change and remuneration, folk or traditional culture stresses common ownership, reinforcement of group values and gradual, evolutionary change legitimised by the community. When ‘Old Skibbereen’ was subsumed into Irish traditional culture, a process that began shortly after publication, its text base became unlocked and fluid. Words and phrases could then be changed. Verses could be discarded or compacted, making the telling of the story less literary, more visceral. And it explains why no two people sing ‘Skibbereen’ exactly the same. Even early on, the choice of melody could be re-examined if there was a better tune to carry the changing word set. Whether by accident or by design, it is easy to imagine someone providing an air that was both slow and mournful, given the gravity of the Skibbereen experience. In this process, Patrick Carpenter’s level of involvement obviously diminishes. In the world of modern popular song that would have major implications, such as literary credit and cash royalties, but not so in traditional song. In a commercial sense, it is likely that Carpenter’s contribution earned him little or no monetary reward, but once his romantic-nationalist lyric was edited by the community—smoothed like the profile of a stone in a fast-flowing stream—his song was added to the musical treasury of the Irish people.

Dan Milner is a lecturer in geography at St John’s University, New York, and a producer for Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

FURTHER READING

P. Donahoe, The wearing of the green song book (Boston, 1869).

O. Handlin, Boston’s immigrants: a study in acculturation (New York, 1974).

J. McLoughlin, One green hill: journeys through song (Belfast, 2003).

R.B. Stott, Workers in the metropolis: class, ethnicity, and youth in antebellum New York City (Ithaca and London, 1990).