Observe the sons of Ulster marching towards the Somme

Published in Issue 6 (November/December 2016), Reviews, Volume 24Abbey Theatre, Dublin, 6 August–24 September 2016

By Eamon O’Flaherty

The most common question posed when deciding whether a work of art can be called a classic is whether it can survive the tendency of most things to decline with age and the passage of time. Even history, which through rhetoric can claim to be one of the liberal arts, is not immune from the ravages of time, as anyone reading, say, Irish historians of the 1970s and 1980s will very quickly realise. Dramatic and lyric poetry, on the other hand, often does have the potential to be, in the poet’s words, aere perennius. So if we are trying to assess the value of a work of art we think about its ability to age without becoming merely a curious artefact relating to a receding moment in time. A second feature necessarily, though less obviously, accompanies this first, which is that the classic work of art is capable not only of conveying a permanent meaning across time but also of being adapted to meet the concerns of our own times and places; because it is universal it is both timeless and always timely.

Above: Even a leaden production could not hide the blood-curdling thrill of the Lambeg drum or the moving solidarity of the doomed men singing their final hymns together.

The theatre is especially good in this respect because each performance is also the product of the interaction of the author’s text and creative direction. Sometimes, as the recently published final volume of Samuel Beckett’s letters revealed, this can survive even authorial disapproval or disengagement. Tackling a revival of Observe the sons of Ulster marching towards the Somme is actually a courageous decision, partly because the play was more or less instantly hailed as a classic when it first appeared and before anyone could really be sure that it was, and partly because so much has happened to the sons of Ulster since the play was first performed in 1985 that we inevitably ask whether it has worn well. Does it give us a better or different perspective on the turbulent history of Ireland and Northern Ireland through the lens of art? Does the current production add anything to the play or, more properly, permit a dramatic expression which says something to the sensibility of the present? None of the answers to these questions are straightforward. The impact of the play is highly qualified by the fact that the production is taking place in the centenary of the Easter Rising and the Battle of the Somme, the two conventional book-ends of the latest stage in a process of apparently endless commemoration in which we are locked as in a recurring nightmare from which we cannot awaken and return to real life. As William Philpott, professor of the history of warfare at King’s College London, wrote recently, the Battle of the Somme ‘has been mythologised to the point of caricature’, and it is the myth rather than the historical event that is the subject of most of the books that have been churned out to exploit the centenary. The same might be said with equal justification of the use of the Somme in recent Irish history. It is deeply ironic that the play which (at one level) set out to deal sympathetically with the forging of a tribal myth in the inferno of the Western Front, and ultimately with the tragedy of that myth’s creation, should be revived even as a similar process of manipulation seems to have become embedded in Anglo-Irish relations, at least as they existed until 23 June 2016. We can thus see the play either as yet another aspect of the engineering of public historical memory or as a provocative intervention which forces the audience to confront the horrifying implications of a cult of identity centred on death and destructive of love and life, even as these emerge from the comradeship of arms and a common cause.

Above: Does the current production add anything to the play or, more properly, permit a dramatic expression which says something to the sensibility of the present?

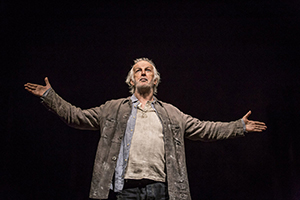

Above: A really memorable initial soliloquy by Seán McGinley as the older Pyper, the sole survivor, was not matched by anything that came after.

Eamon O’Flaherty lectures in the School of History, University College Dublin.