‘Not another book about Dev!’

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2019), Volume 27On the challenges of writing (yet another) biography of ‘the Chief’.

By David McCullagh

In 2010, shortly after the publication of my biography of John A. Costello, I was asked by an interviewer about my choice of subject. I airily replied that, while little had been written about Costello, ‘the last thing the world needs is another book about Dev’. The line was delivered with great certainty and little thought (my wife tells me I do that a lot), but the point appeared to be a good one. Lots of books have been written about Dev; what could be added by another?

And that was my first reaction a couple of weeks later when I bumped into Fergal Tobin, then publishing director at Gill and Macmillan (since renamed Gill Books). As we chatted on Molesworth Street, Fergal asked whether I had any ideas for my next project. I didn’t, but he did. To his question, ‘What about Dev?’, I repeated my earlier reply: there had been literally dozens of books about the man, so what could a new one possibly add?

Fergal suggested that I go away and take a look through some of the books I had mentioned. He believed that there might be scope for a new biography to look at de Valera through the lens of contemporary Ireland, returning to the original sources and giving the ‘long fellow’ credit for his successes, while holding him to account for his failures.

And the more I read, the more I thought Fergal had a point. Some (though by no means all) of the books about de Valera were either hagiographies or hatchet jobs. Many had been written without the benefit of the wide range of new sources that have become available in recent years, and there was certainly scope for a book that went back to the original sources, to strip away some of the myths that have attached themselves to de Valera over the years (some of them, of course, of his own creation).

‘Comely maidens’?

It is surprising, for instance, how many books refer to de Valera’s headquarters in 1916 being in Boland’s Mills, when in fact he was based some distance away at Boland’s Bakery—a trivial enough point, it might be thought, but representative of a tendency for inaccuracies, once made, to be repeated again and again. Similarly, it is notable that critics (usually not historians) attack de Valera for his ‘dancing at the crossroads’ or ‘comely maidens’ radio broadcast of 1943, despite the fact that he didn’t use either of those phrases. To be sure, he used language in the broadcast that was similar and that could be regarded as archaic, but again that isn’t the point: criticism should be based on what was actually said. And even more, it should be based on the entirety of a speech or statement, not on a particular paragraph, and it should be based on the context of the time. The 1943 broadcast, placed in context, is far more interesting and far more revealing than some of the glib attacks on it suggest.

Again, de Valera’s constitution has been repeatedly criticised, not without reason, for being excessively Catholic, but how many of the critics realise that at the time the main complaint was that it wasn’t Catholic enough? De Valera’s relationship with the Church should be questioned, but it is important both to accurately reflect what it actually was and to place it in the context of the time.

Given all that, it was clear that there might be room for such a book. Nevertheless, I had to ask myself whether I really wanted to write it. For starters, it might seem presumptuous for someone who isn’t a professional historian to tackle such a massive subject—but then, plenty of professional historians have no problem doing a bit of broadcasting on the side, so fair is fair.

An over-abundance of sources

More importantly, the scale of the task was daunting. One of the problems in writing the Costello book was the lack of sources about him; in most books about twentieth-century Ireland he might merit a reference or two in the index. With de Valera, of course, there is the opposite problem. There is so much written about him that no one could possibly read every line. Because he was such a dominant figure, everyone talks about him, everyone writes about him and everyone has an opinion about him. To give an idea of the scale of material involved, I cited 349 books and 133 scholarly articles in the bibliography—and there were many more that were read but not quoted. There were 40 years of Dáil debates. There was newspaper coverage to beat the band. There were the personal papers of at least 70 other figures. There were the massive Bureau of Military History and Military Service Pension collections. And there were, of course, de Valera’s own papers, stored on 70 rolls of microfilm in UCD Archives.

There have been suggestions that de Valera was such a meticulous winnower of his own papers that their value is limited, and there is certainly something in that. Nevertheless, despite Dev’s efforts to curate his own history, his papers still contain plenty of material giving an insight into his personality—sometimes in a way he would not have liked.

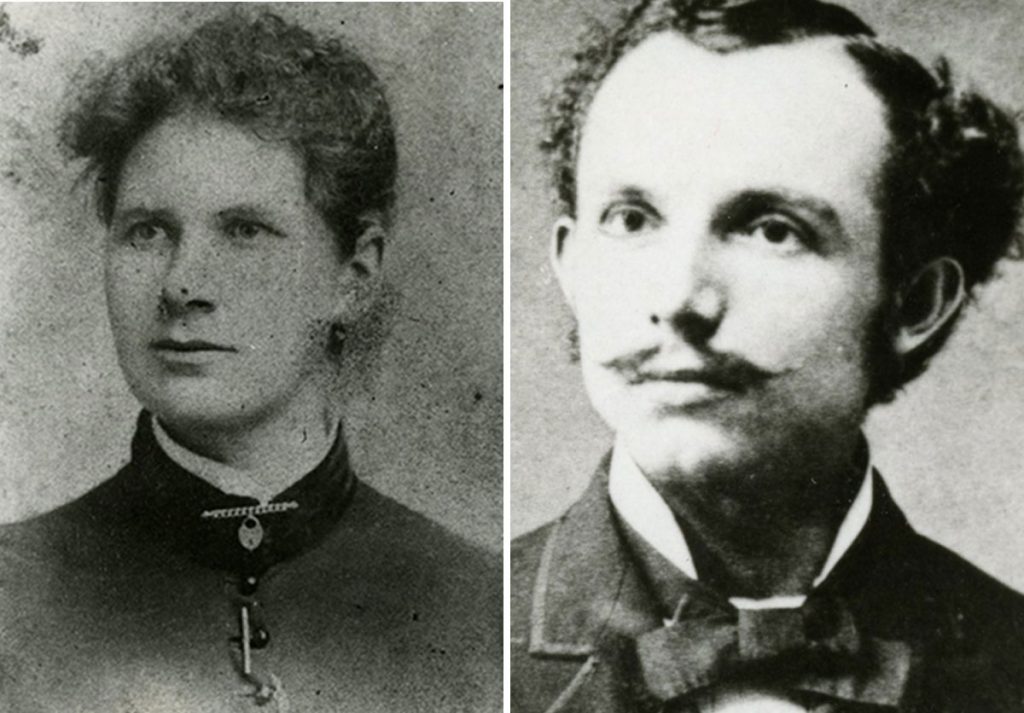

Early on, I was struck by the revelation in his papers of his almost obsessive search for proof of his parents’ marriage. Throughout his life he made repeated and determined efforts to prove that his mother had been telling the truth about her marriage to Vivion de Valera. He never found the proof he sought, but the relentless search disclosed in his papers gives an intriguing clue to the insecurity at the centre of his character, an insecurity that drove him to the very top of Irish politics and made him determined to assert his authority once he got there.

So, the sheer volume of sources was a problem. In the end, it would take seven and a half years to get through all this material (or at least as much of it as I could digest) and turn it into a two-volume biography. That’s a big chunk out of anyone’s life, and had I fully appreciated the scale of the task I might have hesitated even more.

My third concern was my lack of Irish. I had assumed that much of de Valera’s personal correspondence and important political notes would have been in Irish. While many of his love letters to his wife Sinéad were written wholly or partly in Irish, political correspondence was by and large in English—a reflection both of the lack of fluency amongst many of his colleagues and of his own somewhat limited mastery of the language. This meant that, with a little help from some friends, I was able to overcome that difficulty.

My final problem was that I wasn’t sure that I particularly liked de Valera. I didn’t detest him, as so many did and appear still to do, but neither was I a fan. I don’t think a biographer necessarily needs to like his subject to produce good work—Robert Caro’s monumental study of Lyndon Johnson is proof of that—but if you are going to devote the best part of a decade to something shouldn’t you at least find the company congenial?

A curious mix of self-reliance and insecurity

In the end, that objection too was overcome, and if I didn’t come to like Dev I certainly sympathised with him more by the end of the process. I believe that his career was shaped by his character, and that his character was shaped in turn by his early life—by the question marks over his paternity; by his effective rejection by his mother, who sent him home to Ireland to be raised by his grandmother; by the hard grind of his childhood among the labouring class of rural County Limerick; by the insecurity of his patchy academic performance and the difficulty he found in forging a career.

All of this left him with a curious mixture of self-reliance and insecurity; he relied on his own judgement while being over-sensitive to criticism. These character traits were powerfully reinforced during his trip to the United States in 1919–20, where he was feted by massive crowds while also facing political opposition for the first time, from John Devoy and Daniel Cohalan. His ego was boosted while at the same time the fragility of that ego became more marked. This peculiar mixture contributed to his mishandling of the Treaty and the descent into civil war. De Valera evidently bears his share of responsibility for that disaster, but of course there is more than enough blame to go around, and the tendency to hold him solely culpable for the Civil War is just as far off the mark as the claim that he was blameless. Lloyd George, Churchill, Collins, Griffith, Rory O’Connor, Cathal Brugha and others on both sides must all take responsibility for what happened.

So, despite the scale of the task, despite a lack of Irish and despite misgivings about the subject, I got to work in the UCD Archives, the National Archives, the National Library, in archives in London and in Belfast, and of course on the many websites that now give access to archival material on-line. Researching a life is one thing, however; actually writing a book is another. Finally, with a deadline beginning to loom, I had to start writing. And the more I wrote, the more convinced I became that this would not be the one-volume biography Gill had asked for. De Valera’s role at the centre of Irish political life for most of the twentieth century, as well as the scale of the research, simply wouldn’t fit into a single volume. To do the story justice, I felt, required something longer.

Manuscript compared to War and Peace!

The publishers were initially reluctant for (probably sound) commercial reasons. Eventually, however, with the deadline fast approaching and the author only up to the mid-1920s, they agreed to two volumes. Brilliant, I thought, as I finished up to 1932 and sent the manuscript off. A couple of days later a query arrived: did I know how long the book was? I had to confess that I hadn’t checked. After all, this was half of what was supposed to be a single volume, so I assumed that the length would be fine. It wasn’t. The manuscript was compared to War and Peace, and not in a good way. There was no suggestion that the quality would challenge Tolstoy, but the word count certainly did. I’m embarrassed now to admit it, but I had submitted 300,000 words when Gill were expecting 120,000. Some serious culling was required, and quickly.

I spent a miserable couple of weeks hacking away at my unwieldy manuscript. As my finger hovered over the delete button, I would recall spending an entire day in an archive somewhere unearthing the highlighted nugget. Nevertheless, go it must, along with many more like it. I ended up obsessively wondering about the effect of hyphenation on word count, dropping first names where I could and rewriting sentences to save a single word.

I eventually got the word count for volume I (Rise) down to 160,000. The process was pretty awful, and I promised myself never to face the same situation again. Twelve months later, predictably enough, I found myself having to trim volume II (Rule) in the same way, though ‘only’ by around 50,000 words. More discipline during the writing process might have made my life easier, but until I have everything down on the page I find it difficult to decide on the final overall shape. It may not be efficient but it works for me. Eventually.

Seven and a half years in the company of Dev

Now, after seven and a half years, the story is finished. I have spent longer in the company of Éamon de Valera than I ever expected, and as a result have developed (as mentioned above) a certain sympathy for him, if not any particular affection. I believe now, even more than I did back then, that without understanding de Valera’s character we can’t properly understand some of the key events in which he was involved and which he helped to shape: the unification of separatist forces in 1917, the War of Independence, the Treaty débâcle, the Civil War, the slow climb back to power from the abyss of 1923, the loosening of ties to Britain in the 1930s, the new constitution, neutrality in the Second World War, the economic failure of the 1950s, the move towards a more open economy at the end of that decade and the consolidation of the 26-county state in the face of the Troubles. De Valera left his mark on all of these developments, just as his own history left its mark on him. I hope these books can help to clarify some of what happened, and why. I hope, too, that they will help the next person to take up the challenge of interpreting this remarkable life. Will the world need yet another book about de Valera? Of course it will.

David McCullagh is a broadcaster and author of De Valera, Vol. I. Rise 1882–1932 (Gill Books, 2017) and De Valera, Vol. II. Rule 1932–1975 (Gill Books,