MUSEUM EYE: From Ballots to Bullets, Ireland 1918–1919

Published in Book Reviews, Issue 1 (January/February 2019), Reviews, Volume 27National Photographic Archive, Meeting House Square, Temple Bar

nli.ie

By Tony Canavan

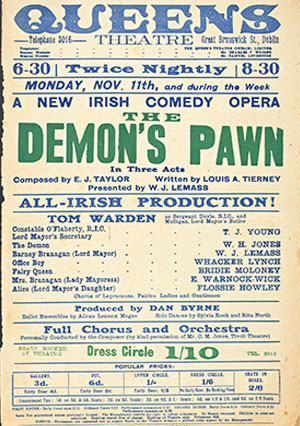

Above: Advertisements for music hall and theatrical productions sit alongside posters for political meetings or anti-conscription rallies.

I have to admit that I was a little surprised by this exhibition (which runs until the end of May 2019), as the publicity surrounding it gave the impression that it was a commemoration of the electoral franchise being extended to women in 1918. Suffragettes and women getting the vote are an important part of the exhibition, but the main theme is how Ireland moved from electoral politics to revolution in the space of a year. Although this is primarily done through the medium of photographs, it also uses artefacts, newspapers and posters.

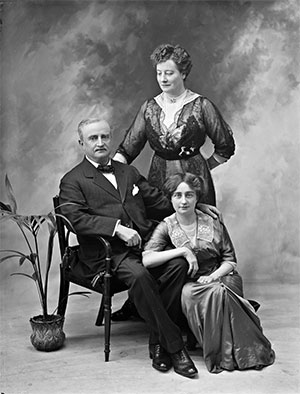

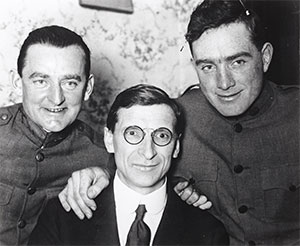

This exhibition is a good example of the use of photographs as a historical source. The range of images on display is impressive, covering all sorts of events and people, high and low, young and old. Some of these stand out immediately. On one side is a photograph of a stately-looking John Redmond posing with his wife Ada and daughter Johanna; on the other is one of an awkward-looking Éamon de Valera squeezed between two friendly GIs on his trip to America.

The story-line of the exhibition begins with the fallout from the 1916 Rising. Even before the 1918 general election it was clear that the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) was in decline and that Sinn Féin was on the rise. It was not just the Rising that undermined Home Rule; other factors, such as the threat to introduce conscription into Ireland, bolstered the case for complete independence. The end of the First World War and the turbulence in Ireland formed the backdrop to the Representation of the People Act, which extended the male franchise and for the first time allowed women to vote, although limited by age and property. Today, we recognise the giving of the vote to women as a momentous development but at the time, as one historian in a video explains, it was not seen as the main thrust of the act and the women’s issue was barely mentioned in parliamentary debates.

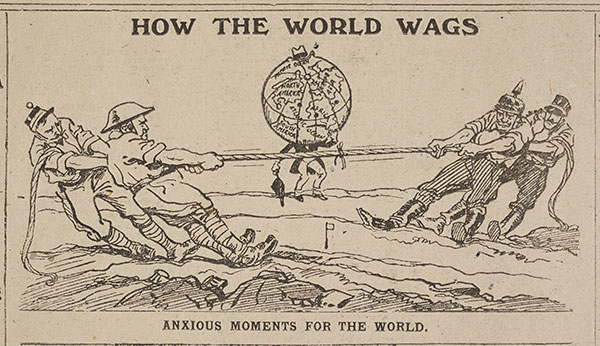

It is easy to follow this exhibition, as it is well laid out and the images are dated. For example, a newspaper cartoon about the progress of the war is dated 31.03.1918; that of John Redmond is dated 26.01.1914. This is useful for putting the photographs in context and for following the development of events. And events both big and small unfold through the photographs. Some of these are staged, while others are snapshots of incidents taken by newspaper photographers. Along with the captions, the effect is to give immediacy to what we are seeing, as if all these happenings were current affairs.

Above: On one side is a photograph of a stately-looking John Redmond posing with his wife Ada and daughter Johanna; on the other is one of an awkward-looking Éamon de Valera squeezed between two friendly GIs on his trip to America.

In the side gallery off the main one we get a flavour of the period. Advertisements for music hall and theatrical productions sit alongside posters for political meetings or anti-conscription rallies. A photograph of Constance Markievicz contrasts with one of marching soldiers. We can appreciate how the issue of votes for women got caught up with other political issues in the run-up to the general election. This area illustrates the range of things that were happening, such as the Paris Peace Conference, the Limerick ‘soviet’ and the first stirrings of violence against British authority.

Dominating this area, however, is a large map of Ireland showing the results of the 1918 election constituency by constituency. This really brings home the extent of the Sinn Féin victory, the demise of the IPP and the size of the unionist minority in the north-east. Below this is a large video screen featuring interviews with leading Irish historians, who talk about the different aspects of this period and place the events in context.

This would already be enough for any exhibition, but there is more upstairs. Here are the ‘Revolutionary Lives’, where the exhibition homes in on particular individuals who represent the different strands of change in post-war Ireland. For example, there is Máire Comerford, described as a ‘Rebel with a Cause’; Thomas (Tom) Johnson, a ‘Labour Leader’; and Kathleen O’Brien, a ‘Protesting Playwright’. If the flow of information downstairs can seem a bit bewildering, these photographs give you a chance to slow down and appreciate that sweeping social changes are the combined experiences of individual people.

One could spend a lot of time at this exhibition, examining each photograph or comparing and contrasting the different aspects of the period. There is something here for everyone, and the designers even had children in mind. There are worksheets and handouts as well as the chance to dress up in period costume and act out what it was like to live during these heady events. I can imagine that a visit to the exhibition would be a worthwhile outing for any class.

One could spend a lot of time at this exhibition, examining each photograph or comparing and contrasting the different aspects of the period. There is something here for everyone, and the designers even had children in mind. There are worksheets and handouts as well as the chance to dress up in period costume and act out what it was like to live during these heady events. I can imagine that a visit to the exhibition would be a worthwhile outing for any class.

I have one quibble with the exhibition and that is where it says that ‘the biggest challenge for the fledging first Dáil Éireann was building a nation’. What they really mean is building a state. The Irish nation already existed: that is what was seeking independence.

Tony Canavan is editor of Books Ireland.

Above: A newspaper cartoon about the progress of the First World War (31 March 1918).