Museum Eye: A Dubliner’s collection of Asian art: the Albert Bender exhibition

Published in General, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2009), Reviews, Volume 17

Albert M. Bender c. 1941—always thought of himself as Irish. (Grabhorn Press, San Francisco)

National Museum, Collins Barracks, Dublin 7

www.museum.ie

Tues.–Sat. 10am–5pm, Sun. 2pm–5pm

by Tony Canavan

Among the many good reasons for visiting the National Museum, Collins Barracks, another has been added in the form of the Albert Bender collection. It consists of about 260 items reflecting Asian art in its different forms, from metalworking and pottery to tapestry and printing.

The story of how it ended up in the National Museum is as interesting as the exhibition itself, since not only museums in the United States but also the Louvre in Paris wanted all or some of Bender’s collection. He was born in Dublin in 1866 into a prominent Jewish family. Like many of his fellow Irishmen, Bender emigrated and made his fortune abroad. By the turn of the twentieth century he was one of San Francisco’s leading insurance brokers and able to indulge his taste for Asian art. He did not go out and seek the art himself but worked through dealers who brought him the finest objects from Tibet, China, Japan and elsewhere.

In 1931, in honour of his recently deceased mother, Augusta, Bender decided to donate his collection to the National Museum of Ireland. The 260 objects were transferred to the museum over the following years. This collection of international importance was a significant boost to the newly independent state and paved the way for further similar donations, most famous of which is the Chester Beatty Library. In the wider context, it says something about the position of the Jewish community in Ireland that, despite leaving Dublin as a teenager, Bender always thought of himself as Irish and wanted to benefit his homeland. Bizarrely, the head of the National Museum at that time was the Austrian archaeologist and Nazi Adolf Mahr. He worked closely with Bender in coordinating the hand-over of the collection, and by all accounts they had a cordial relationship. Reflecting the esteem in which Bender and his collection were held, Eamon de Valera himself officially opened the Augusta Bender Memorial Room in June 1934. Albert Bender died in San Francisco in 1941, leaving art and antiquities to museums in the USA and elsewhere.

‘Famous Places of the Eastern Capital, Myojin Shrine in Kanda’, by Utagawa Hiroshige, c. 1832–9, Japan.

Unfortunately the collection was subsequently put into storage, and only the additional space provided by Collins Barracks has enabled it to be put out on permanent display again. The National Museum should be congratulated on how it has maximised the use of a building clearly not meant to house a museum. This does mean that to get to the Bender exhibition you have to pass through the collections of antique furniture and clothes, but that is not a bad thing. The ticking of the barracks’ clock tells you that you are coming to the Bender exhibition.

It begins in a few small rooms containing objects such as small figurines originally housed in a Daoist temple, intricately carved snuff bottles from Qing dynasty (1644–1912) China and heads from Buddhist temples. Worth looking out for is a charming earthenware duck from the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220), an example of the kind of item placed in the tombs of the wealthy. On the way into the exhibition proper, you pass two elaborate funerary jars that would have contained rice as an offering to the gods in a tomb.

The main gallery is a large room where you are struck by the colour and brightness of the objects as soon as you enter. It is probably best to start with the electronic catalogue on the interactive screen (when it is working!) as it tells you about the collection and individual artefacts, although the information panels in the display cabinets are more than adequate. The first display cabinet has fine examples of Chinese metalwork mostly from the eighteenth century, such as an elaborate incense burner and a tall wine flagon used by the Mongol nobility. Another has pottery, the most impressive of which is a sweetmeat dish divided into sections depicting the Eight Happy Mortals of Chinese legend. Another cabinet has a collection of Japanese carved figures in full dress. The Shotoku Taishi figure, especially the expression on his face, is particularly impressive.

The exhibits are interspersed with information telling us about Bender, his collection and his life—he was a patron of the arts and remained in contact with the leading Irish cultural figures of the day. One exhibit tells us also about his support of artists in the USA, such as Diego Rivera, husband of Frieda Kahlo, and his bequests to American museums and galleries. The back wall of the room has a tapestry depicting the legendary Chinese One Hundred Boys, dating from the eighteenth century. Next to this is more information on Bender and writers like W. B. Yeats, and a nice low-tech exhibit where you can try your hand at Japanese printing.

This leads appropriately on to the next wall, which has about 40 Japanese woodblock prints. These are amazingly intricate and fine in detail, depicting the signs of the zodiac, landscapes and people. The prints of courtly ladies are very beautiful, portraying them doing everyday things like reading a letter, holding a lantern or walking in a garden. It is worth going to see these alone.

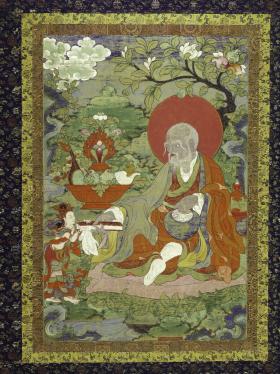

Thangka painting of the Arhat Pindola Bharadvaja, Tibetan-Buddhist, eighteenth-century, probably from Gansu province, China.

All these artefacts, however, great though they are, are not the main focus of the exhibition. This is the Buddhist tapestries, or thangkas, that occupy the bulk of the gallery. These date mainly from eighteenth-century Tibet and depict important figures from Buddhism such as Hashang, a monk-scholar from the seventh century. Each tapestry has an intricate display of colours, symbols and landscapes surrounding the main figure. These are worth spending time over, since the longer you look the more you see. In the final cabinet is the robe of a Daoist priest from seventeenth- or eighteenth-century Tibet, an opulent vestment made of silk with gold thread. The front of the robe depicts astronomical symbols like the earth, moon and stars, while the back has a tower surrounded by a dragon, a snake, a tortoise, etc. This robe rewards close observation as the many symbols on it are not immediately obvious.

Comparisons with the Chester Beatty Library are unavoidable, but one is not better than the other. The Chester Beatty has more artefacts but the bijou nature of the Bender collection means that it can be taken in in one visit and it displays a spectrum of Asian art. Bearing in mind that this collection was coveted by the Louvre, there can be no doubt about its significance and it is a stunning display, well worth spending time over. HI

Silk-with-gold-thread Daoist priest’s robe, seventeenth/eighteenth-century, China.

(All images, bar Bender sketch: National Museum of Ireland)