Muirchú’s Life of St Patrick and the history of fifth-century Ulster

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2018), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 26What can Muirchú’s Life of St Patrick (c. 688) tell us about the political history of late fifth-century Ulster, and in particular the hostile relationship between the Uí Néill and their allies the Airthir, a tribe of the Airgialla, and the Ulaid, mentioned at the close of Muirchú’s Life? Does it provide any clues to the year in which St Patrick died, the starting point for the events described at the end of the work?

By Patrick McDonagh

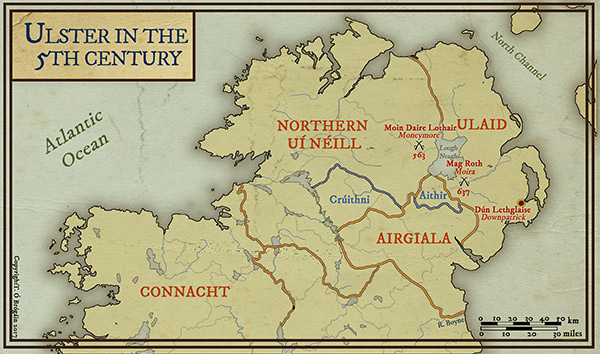

In Muirchú’s Life of St Patrick we are told that after the death of the saint ‘a dreadful conflict, extending even to war, arose […] about his relics’. This conflict was ‘between former friendly neighbours, now deadly enemies, the Uí Néill and the Airthir on the one hand and the Ulaid on the other’. Thankfully, owing to a supposedly miraculous flooding of the Muin Daim, fighting was prevented. Later, however, after ‘Patrick had been buried’, war broke out once more, and the Uí Néill and the Airthir ‘forced their way to the place where the blessed body was’, which, as we have previously been informed, was at Dún Lethglaise (Downpatrick). After carrying off what they believed to be the body of the saint, they reached the River Cabcenne (near Armagh?), where the body disappeared—a miraculous illusion for the sake of harmony and peace between the warring tribes. With this strange description of political events Muirchú ends his Life, keen to emphasise that the death of St Patrick led to conflict over his relics between the powers of the north.

When did St Patrick die?

We can date this episode to some point in the fifth century after the death of St Patrick, which occurred either in 461 or 493. In the Annals of Ulster there is a cryptic reference in 496 to ‘the storming of Dún Lethglaise’. If one takes Muirchú as a serious guide for the fifth century, then the death date of 493 seems to fit better within the wider chronology that he propounds. In his story, after the death of St Patrick the Uí Néill and Airthir successfully invade Ulaid and seize the body of the saint, only to be disappointed when it turns out to be an illusion. He writes that they ‘imagined themselves carrying off the holy body’ with the aid of oxen and a wagon. In others words, Muirchú is describing a successful raid into Ulaid territory, where loot was presumably taken in addition to the apparent body of St Patrick. This success would correspond with the annal entry regarding the storming of Dún Lethglaise in 496. This location is the very same as the one suggested by Muirchú as the resting place of St Patrick. Dún Lethglaise in this period has an ecclesiastical—in particular, monastic—association, and this annal entry is very suggestive of a monastic centre being sacked in 496. Even if the entry refers to the storming of a royal fort, surrounding sites would also have been looted. Nevertheless, there are issues with this interpretation, not least that the cryptic nature of the annalistic reference makes it impossible to say who stormed Dún Lethglaise and for what reasons.

There is also the possibility that this annal entry, referring to the storming of Dún Lethglaise, was a later addition or interpolation influenced by a reading of Muirchú’s Life—a serious objection. In other words, a later chronicler had read Muirchú’s Life and knew that the battle he described at Dún Lethglaise happened after the death of St Patrick, and accordingly placed it appropriately in the years after his death. This objection can be dismissed, however, because if it were a later interpolation a gloss would have been provided for the entry, to explain its significance. One may counter this by suggesting that the interpolator assumed that his readers would also know Muirchú’s Life and realise the significance of the entry, yet this seems implausible. Furthermore, it bears no signs of being a retrospective entry, such as the clearly retroactive additions of monastic founders’ birth dates. Therefore it can be seen as a genuine annalistic record from the late fifth century, reproduced with little knowledge of its importance.

Muirchú wrote his text sometime after 688, and it is not impossible that he had read or consulted an earlier version of the annals. He may have been influenced by this reading and decided to combine the entry for the storming of Dún Lethglaise in 496 with the death of St Patrick in 493 to provide a coherent story explaining why St Patrick was not buried in Armagh. Muirchú was an Armagh propagandist during a time when Armagh was trying, successfully, to assert its primacy in the Irish church. As the supposed ‘see of St Patrick’, it was clearly a matter of some embarrassment that the saint was not buried there. Indeed, Muirchú could not get around the inconvenient fact that his body was buried in Saul or Dún Lethglaise yet had to argue that Armagh nonetheless had more ecclesiastical significance. While this is likely to have influenced how he told the story, it is not a fully satisfactory explanation for the inclusion of the storming in Muirchú’s Life.

Above: St Patrick standing on a snake in Purgatory, from a 1451 English manuscript. (British Library)

Muirchú himself seems to have come from near Armagh, and his Life shows a wealth of detail about the land of Antrim and north Down, where Saul and Dún Lethglaise are located, which would support the view that he based his account of warfare on genuine events. As a native of the region, he may well have been familiar with a story passed down orally about such a battle. The chronology he offers, together with the corresponding annal entry for the storming of Dún Lethglaise, provides, as a corollary, evidence that the death of St Patrick can be dated to 493 and not 461, for there is no annal entry in the years following 461 for a major battle or sack near Dún Lethglaise. This could perhaps be an omission, or more likely is due to the fact that there was no such battle in the 460s. Muirchú’s text preserves a memory of a series of battles and raids in the 490s to acquire possession of the body of St Patrick. It is more than a coincidence that the storming of Dún Lethglaise and the second death date of St Patrick are closely aligned in the annals. This allows us, based on Muirchú’s account, to place St Patrick’s death in 493. By a close analysis of his Life and the annals, much light can be shed on the political history of late fifth-century Ireland and, strikingly, on when St Patrick died.

There are, however, possible objections to the use of Muirchú’s Life to draw conclusions about the history of fifth-century Ulster, being as a whole somewhat deficient in reliable historical information. One problem with the source is that it suggests that Uí Néill power was at a level comparable to that of the late seventh century. The Uí Néill predominance in the north of Ireland was starkly revealed at the battle of Móin Daire Lothair (near Moneymore, Co. Derry), when they won a crushing victory over the Cruthin. Yet predominance does not mean supremacy, which was not achieved until their major victory at Mag Roth (Moira, Co. Down) over the Ulaid in 637. Whether this predominance existed in the late fifth century is unclear. Dún Lethglaise is situated well east of the River Bann and it seems unlikely that the Ulaid had yet been pushed across the Bann, something that became more of a reality following Móin Daire Lothair. The Uí Néill may have lacked the power at this point to strike so far east. The alliance that Muirchú describes between the Uí Néill and the Airthir seems to be a convenient gloss designed to flatter local delusions of power. Armagh was within the kingdom of Airthir and in the late seventh century the Uí Néill were much more powerful than this kingdom. Whether this relationship of equals held in the fifth century is debatable. The Airthir, like the rest of the Airgialla, would have been under Ulaid hegemony, certainly in the fourth and early fifth centuries, as far as can be understood. Warfare between the Airgialla and Ulaid is also rare in the early annals. This may hint at the superiority of the latter, the Airgialla’s overlords.

Pivotal moment in the subsequent northern hegemony of the Uí Néill?

As we leave the murky fifth century and enter the more comprehensible sixth century, what is relatively clear is that the Ulaid exist in a more truncated form, though perhaps still stretching south to the Boyne. The glory days of Conchobar Mac Nessa, however, are quite clearly long in the past, with their ancient cóiced of Ulster now much smaller and their former hegemony gone, and the Airgialla existing as a buffer between them and the Uí Néill. If we look at the annals for the later seventh century, which are much richer than for the fifth century, we see no parallel to Muirchú’s account of an alliance of Uí Néill and Airthir sweeping east into the heart of Ulaid territory and sacking Dún Lethglaise. Muirchú is providing, in a distorted form, a dim recollection of political events near the turn of the fifth century, pivoting around the death and body of St Patrick.

Given that the Airthir are allied with the Uí Néill, we can tentatively argue that the hostilities took place at a time when the Airgialla were not under the suzerainty of the Ulaid. Interestingly, it might provide the moment when the hegemony would begin to tilt in favour of the Uí Néill in the northern half of Ireland. Later Uí Néill historians liked to promote the myth that the fall of the Ulaid can be dated further back, to the early fourth century, yet this is obviously political propaganda. Muirchú’s Life tells of a successful raid deep into Ulaid territory, around Dún Lethglaise, with the Uí Néill and Airthir certainly carrying back spoils, as well as the supposed illusion of St Patrick’s body. Combined with the annalistic reference to the storming of Dún Lethglaise in 496 and St Patrick’s second recorded death of 493, we see tantalising evidence of the moment that perhaps marked the downturn of Ulaid political might and saw their historic control of Ulster collapse in the face of Uí Néill expansionism. That a raid could penetrate so far east across the Bann must reflect the nadir of the Ulaid’s fortunes.

This is when we can rightly date the fall of the Ulaid kingdom, resulting in its smaller form in the sixth and seventh centuries. Muirchú’s alliance of the Airthir with the Uí Néill starkly reveals the new political realities operating in late fifth-century Ulster. We can refute the suggestion that Muirchú’s Life has little to offer in terms of understanding the period. That Muirchú’s Life has not been utilised in this fashion is surprising, for despite being written some two centuries after the death of St Patrick it provides a glimmer of events long past. Authors of this period utilised a great deal of oral history, with all its vagaries, yet its usefulness should not be underestimated. Muirchú underlines this when he comments that others had sought to recreate the life of St Patrick from the traditions of their elders. It was likely such traditions that provided Muirchú with his knowledge of the battle. Though he used this event to explain why the body of St Patrick was buried in Dún Lethglaise rather than Armagh, it is unclear whether this was the motivation behind the original attack. For the purposes of hagiography it would inevitably be distorted, even if the original motives were a desire for plunder or a demonstration of power.

Conclusion

Above: St Patrick’s grave at Down Cathedral, Downpatrick (Dún Lethglaise), Co. Down.

Patrick McDonagh is a Ph.D student at Trinity College Dublin, researching the Mortimer family in late medieval Britain and Ireland.

Read More:

THE COUNCIL OF IRISH CHIEFS’ AND CLANS’ PRIZE IN GAELIC HISTORY 2019

FURTHER READING

J.F. Byrne, Irish kings and high-kings (Dublin, 1973).

L. de Paor (ed.), Saint Patrick’s world: the Christian culture of Ireland’s apostolic age (Dublin, 1993).

D. Ó Cróinín, A new history of Ireland, Vol. I. Prehistoric and early Ireland (Oxford, 2005).

R. Sharpe (ed.), Adomnán of Iona: Life of St Columba (London, 1995).