Monstrum horrendum

Published in Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2019), Volume 27A newly discovered poem from County Offaly in the 1641 Rebellion.

By Jane Maxwell

Among a small cache of papers relating to the Digby family of Warwickshire, now in the library of Trinity College, Dublin, is a previously unknown seventeenth-century poem about an event that took place in the Irish midlands during the 1641 Rebellion. It is signed only with its author’s initials, which have frustrated attempts at identification. Despite its anonymity, it is significant as a rare literary response to events in that turbulent time. The initials certainly present us with a conundrum because the energy of the poem is derived from the experience of Lettice Digby, famous for having defended her castle at Geashill, Co. Offaly, when it was besieged during the rebellion by the O’Dempseys. Could it be a collaborative piece, written by someone working with Lady Digby in her old age? Or was it written by a hitherto unrecorded member of the Digby or Fitzgerald family who was present in Geashill Castle during those tense months and could thus speak with the command of detail evident in the poem?

Above: Portrait of Lettice Digby. (Sherborne Castle Estates)

Lettice Digby

Lettice Digby (c. 1580–1658), Baroness Offaly, was the heir of Gerald Fitzgerald. At eighteen she married Sir Robert Digby of Coleshill, Warwickshire, and had three daughters and seven sons; she was widowed around 1618. Her castle at Geashill was besieged more than once by the Catholic O’Dempseys; although offered relief by the military commander, Sir Charles Coote, after the second attack, she chose to stay and defend her home. She only agreed to leave after a third attack in October 1642.

In leading the defence of her castle, Lady Digby became one of a small number of noblewomen in Ireland who were actively involved in the rebellion as leaders, and one of only two—Lady Dowdall of Kilfinny Castle in Limerick being the other—who produced written evidence of their experiences. Lettice Digby’s evidence consists of correspondence with her attackers during the siege in early 1642. These letters were widely read, having been published almost immediately in England as part of a propaganda campaign; they also exist as copies included in the 1641 Depositions. In their letters to Lady Digby, Henry O’Dempsey and his brother Lewis, Viscount Clanmalier, claiming to be loyal subjects of the throne, demanded that Geashill Castle be handed over to them, promising the inhabitants safe passage to Dublin if they went peacefully. They threatened to burn the town and kill the inhabitants if obliged to take the castle by force. Lady Digby in her reply poured scorn on the idea of entrusting her safety to the hands of the O’Dempseys.

The haughty tone of the letters, along with her obvious bravery, secured Lady Digby’s reputation, and the account of the sieges became embellished over time in a manner that attests to the attraction of her story in popular imagination. For example, it was said that she was looking out a window when a bullet, narrowly missing her, hit the wall beside her head. She took out a handkerchief and made it appear as though her only concern was to wipe away the debris from the damaged site. In fact, this story originated with the countess of Mornay’s successful defence of Dunbar Castle in Scotland three centuries earlier.

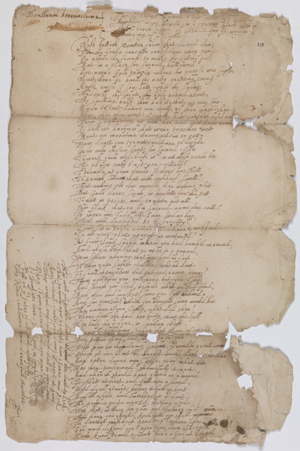

Above: Monstrum horrendum—the manuscript of the poem about the siege of Geashill, before conservation. (TCD)

The poem

The newly discovered poem was purchased by Trinity College in 1998 at an auction in London, along with other material relating to the Fitzgerald/Digby family. Its significance may have gone unnoticed in the intervening years owing to the fact that it was catalogued by reference to its first line, with its religious tone, rather than by its full title.

The ‘sow’ referred to in the poem’s title was an ancient name for a mobile wooden shield under which an attacking army could attempt to undermine a defensive wall while being protected from missiles launched from above. In their attempts to break into Geashill Castle it is known that the O’Dempseys first tried to undermine the walls of the castle using just such a tactic. The poet takes the opportunity presented by this zoomorphic analogy to mock her enemies. It would appear that this was quite a common linguistic usage; Lady Dowdall in Limerick used the same language when she reported her successful repulsing of a similar attack with the words ‘I killed their pigs’. The poet addresses the sow directly. It is identified as a demonic (‘hellish’) animal and accused of having defiled a sacred place—the vicar’s house in which it was built—with its ‘filthy bed’. The poet then goes on to use the language usually employed when describing a person as a pig (and there may be an element of gendered insult intended by using female terms to refer to a military machine); the sow is an ugly, obese animal (particular insults against the female form) and ignorant, as suggested by its ‘grunting tongue’. Clearly these insults are meant to extend to the sow’s owners, with the implication that they, too, are unholy as well as ill-mannered and misshapen.

While the title of the poem places the spotlight on one particular military strategy, the author also turned her attention to another aspect of the O’Dempseys’ failed efforts. When the sow proved unsuccessful, the O’Dempseys constructed an enormous gun, ‘a great brass ordinance’ as it is described in the 1641 Depositions, which also failed. Some accounts specify that the gun was ‘cast three times’ by a smith from Athboy out of ‘sevenscore’ pots and pans; this level of descriptive detail speaks of the strength of the oral tradition around the event and is a further iteration of a gendered insult in its suggestion that this mighty weapon was constructed out of domestic utensils. The failure of the gun was mentioned in passing in the Digby–O’Dempsey correspondence and is roundly mocked in the poem.

Author?

Who is the author of this lively poem, who confidently signed off with an authorial ‘Dixi’ (‘I have spoken’)? The manuscript is signed with the initials ‘F.M.’ (the first initial being in a form that could also be read as an I or J). The script is a sophisticated italic hand, which was common in well-educated families; it is very similar to Lettice Digby’s own handwriting and, for example, to that of the earl of Cork, father of Digby’s daughter-in-law, Sarah.

The poem could have been written entirely by a member of the household at Geashill Castle whose name was not recorded in the history of events there in 1642. The make-up of Lady Digby’s household is not known with certainty but it is known that she had daughters-in-law and grandchildren living with her both in Geashill and in Warwickshire; perhaps the author of the poem is to be found among them. In considering the language of the poem, we must ask who, other than the chatelaine or a significant relative, could have referred to the fortress as ‘our’ castle. The poem’s invitation to the O’Dempseys to ‘come let us parle awhile’ also carries the tone of a commander of the situation, so perhaps Lady Digby had some role in the composition. Lady Digby is known to literary history for one poem and a four-line epitaph, written in her old age and published in the early twentieth century. These were transcribed on the author’s behalf, since Lady Digby had become blind towards the end of her life. If, as may reasonably be assumed, the recently uncovered poem was written after Lady Digby’s return to England, she may at the time of writing have already begun to lose her sight, which would explain the necessity of a collaborator.

What is incontestable is that the poem clearly conveys the voice and experience of Lettice Digby. The author must have been inside the castle during the siege or was someone sufficiently close to Lady Digby to be familiar with the story of her experience. It cannot be doubted that the tale of the sieges of Geashill would have been frequently retold by Lady Digby. The fact that these experiences loomed large for her for the remainder of her life is attested to by the existence of a portrait of her, painted in old age, which carries the motto, from the Book of Job, ‘I am escaped with the skin of my teeth’.

Significance

Above: Geashill Manor, with the remains of the old castle, in 1869. (Offaly History Archives)

This poem is significant for a number of reasons, beyond its principal subject. It is interesting to students of manuscript culture—the private production, circulation and impact of texts by both women and men—which has become the subject of research interest over the last few decades. Scholarship now acknowledges the severe limits of any survey of literature that concentrates only on published works. This manuscript, since it is clearly a fair copy of a finished work, could have been made as a presentation manuscript to be shared beyond the author’s immediate circle. The fact that the final verse is written sideways in the left-hand margin, to avoid the use of a second sheet of paper or the verso of the single sheet, also suggests that the paper was intended to be folded for delivery to a distant reader. Further significance will be added to the poem if the identity of the transcriber is eventually discovered, which will not only introduce an unknown poet to seventeenth-century Ireland but also enlarge what we know of the Digby–Fitzgerald familial network and the make-up of Lady Digby’s household, and may possibly add detail to the history of the sieges of Geashill. Regardless of how the conundrum embodied in this manuscript is resolved, the solution will include Lettice Digby. This poem could not have been written without her; even if she did not actively collaborate with the author, the poem celebrates what she would have seen as her moral victory.

Jane Maxwell is Assistant Librarian in Trinity College Library, Dublin.

Read More:

FURTHER READING

N. McAreavy, ‘“Paperbullets”: gendering the 1641 rebellion in the writings of Elizabeth Dowdall and Lettice Fitzgerald, baroness of Offaly’, in T. Heron & M. Potterton (eds), Ireland in the Renaissance c. 1540–1660 (Dublin, 2007).