Michael MacWhite’s memoirs of the Sinn Féin delegation in France, 1919–21

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2019), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 27An unpublished record of what was, to all intents and purposes, Ireland’s first diplomatic mission.

By John Gibney

Above: A postcard showing ‘Uncle Sam’ ushering Ireland, in the form of a uniformed member of the Irish Volunteers, into the Paris Peace Conference. Hopes that the United States would support Irish claims for independence were, however, wildly optimistic. (NLI)

The Royal Irish Academy’s Documents on Irish Foreign Policy (DIFP) project publishes selected documents from a range of archives ‘which are considered important or useful for an understanding of Irish foreign policy’. The vast majority of these are held in the National Archives of Ireland (NAI), but another repository of which the DIFP makes extensive use is the UCD Archives, which retain the personal papers of many of the key politicians and diplomats involved in shaping independent Ireland’s foreign policy. These collections proved invaluable in the recent compilation of an illustrated centenary history of Irish foreign policy, given that they contain photographs, manuscripts and personal effects that would not normally be published as part of the DIFP project. A notable case in point is the extensive archive of the journalist and diplomat Michael MacWhite (1883–1958), especially his unfinished and unpublished memoirs.

MacWhite’s career

MacWhite was from Glandore, Co. Cork, and in 1900, after leaving school, he travelled to Dublin to take the entrance exam for the civil service. On this visit MacWhite made the acquaintance of Arthur Griffith, declined to enter the civil service and travelled to London instead, working as a bank clerk and becoming involved in a range of nationalist cultural organisations—and also, it seems, in the IRB. Griffith was an intellectual influence as well as a friend, and in 1908 MacWhite and Seán Mac Diarmada were involved in setting up Sinn Féin branches in West Cork. MacWhite had a gift for languages and later became a journalist on the Continent, reporting from as far afield as the Balkans and the Middle East. He joined the French Foreign Legion in 1913 and saw service during the First World War, including at Gallipoli and in Macedonia; he was wounded twice and won the Cross de Guerre three times, rising to the rank of captain. He later enjoyed a lengthy and distinguished career in the Department of External Affairs, serving as the Irish Free State’s representative to the League of Nations (1923–9), playing a key role in Ireland’s admission to the organisation, and subsequently as Irish minister (effectively the ambassador) to the US (1929–38) and Italy (1938–50). In the late 1940s and early 1950s he started writing his memoirs. Numerous drafts survive, relating to all aspects of an undoubtedly colourful career, but of particular interest, given the ongoing centenaries of the Irish revolution, are those that relate to his time in France as a member of what was, to all intents and purposes, Ireland’s first diplomatic mission, in 1919–21.

The handwritten drafts of MacWhite’s memoirs of France form part of his papers in the UCD Archives (P.194/673-80). Throughout the War of Independence, Dáil Éireann made concerted efforts to harness international opinion to the cause of Irish independence, and MacWhite became involved in these from an early stage. He had been in New York for the Armistice of 1918 as part of the French military mission supporting the ‘Liberty Loan’ (the bond drive organised by the US government to raise funds for the Allies) before returning to France, and thence to Dublin on leave.

According to his memoirs, MacWhite arrived in Ireland on 28 December to find many of his old associates imprisoned thanks to the ‘German plot’ allegations; he subsequently made contact with Sinn Féin, and Harry Boland apparently gave him typed copies of the First Dáil’s Declaration of Independence, Democratic Programme and ‘Message to the free nations of the world’. (Seán T. Ó Ceallaigh, who subsequently became the Dáil’s principal emissary in Paris, later recalled having encountered MacWhite in uniform at Dublin City Hall and claimed that he had also provided him with copies of the same documents.) MacWhite was asked to bring these with him on his return to France and to get them published in various newspapers to publicise the cause of Irish independence.

Sinn Féin emissary in Paris

MacWhite returned to Paris on 22 January 1919 and from then on was essentially a Sinn Féin emissary in the French capital. He requested demobilisation from the Foreign Legion (and did so equipped with cigarettes and ‘a couple of pounds of sugar’ to help his case with the relevant officers). In the end this proved to be a protracted process that went on for months; his papers were in the Legion’s headquarters in Algeria, but he was permitted to remain in Paris. He soon realised the advantages of keeping his uniform, as it ‘gave me more liberties than were then accorded to civilians’; as Ó Ceallaigh later recalled, his uniform ensured that MacWhite was always ‘most acceptable to the French’.

To aid matters, Ó Ceallaigh had given MacWhite an introduction to the journalist William O’Mahoney, with whom he and another future Irish diplomat, Leopold Kerney, established La Société Franco-Irlandaise. The day after Ó Ceallaigh arrived in Paris in February 1919 as the ‘accredited envoy of the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic’, MacWhite and O’Mahoney called on him at the Grand Hotel (which became the headquarters of the Sinn Féin delegation in Paris), though as he had signed in using Irish characters the staff had trouble finding him.

Above: Michael MacWhite serving as a member of the French Foreign Legion, guarding a German prisoner at an unidentified location during the First World War. After demobilisation he retained his dress uniform, which came in useful when seeking to create a good impression in Paris. (UCD Archives)

MacWhite had the task of garnering publicity and was well regarded by his colleagues. He was the correspondent for the United Irishman newspaper and described his involvement in the production of a French edition of the Dáil’s propaganda organ, the Irish Bulletin, which was circulated to newspapers in France, Belgium and Switzerland, as well as to politicians and ‘university professors’; Irish students at the Sorbonne apparently helped in its production. There were, however, limits to what the Irish delegation in Paris could achieve, as the French were, at this juncture, ‘most particular’ to avoid giving offence to the British. Attempts to gain access to the Peace Conference faltered in the face of British opposition, while the ‘German Plot’ arrests of 1918 had damaged the Irish cause in many French eyes. Yet it was made clear to MacWhite that, in terms of getting a hearing, there were ‘certain difficulties that could with a little good will be surmounted’. To get coverage, the Irish would have to pay, for as one editor told MacWhite with remarkable frankness, ‘the French press is the most venal in the world. The Irish should understand that and act accordingly.’

MacWhite was officially the secretary to the Irish delegation from March 1920 onwards, and his memoirs provide a level of texture and detail on the activities and workings of the Irish mission in Paris, with some incidents standing out. While prospects of admission to the Peace Conference faded rapidly, the delegation continued to highlight the Irish independence struggle as best they could, and in various ways; there was some degree of sympathy for the Irish cause in France. On one occasion MacWhite travelled to Bordeaux to give a lecture on Sinn Féin, organised by a ‘Professor Duckett’, one of whose ancestors had apparently made a poor impression on Theobald Wolfe Tone. MacWhite was surprised at the Irish heritage of the city, and while there visited the grave of the United Irishman James Napper Tandy.

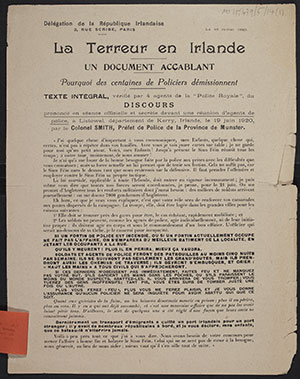

Above: ‘La Terreur en Irlande’—a French-language propaganda bulletin produced by the Sinn Féin delegation in Paris, 1920. (NLI)

MacWhite’s memoirs include his recollections of an address he made to the Grand Orient de France, an enormously prestigious—and, it was assumed, influential—Masonic lodge, which, as he put it, wanted ‘to satisfy themselves as to the truth of our propaganda’. The audience he addressed included diplomats, writers, lawyers and politicians; MacWhite came prepared, as he had been warned to expect a grilling, ‘the result of which might be detrimental to the object we had in view’, and which might even result in a damaging denunciation of Sinn Féin from influential official quarters. He was well received, though his account of British policy in Ireland was challenged by an English member of the lodge (who was apparently a British diplomat). In turn, another member came to MacWhite’s aid, stating that his own father, who was from India, had once been whipped by British officers, and asked whether such officers could be described as gentlemen by anyone present.

Hoche sesquicentennial

The emphasis on British repression in Ireland was a key propaganda tactic deployed by Sinn Féin overseas, but all publicity was good publicity, and MacWhite recalled playing a central role in one incident that showed a good deal of imagination and audacity. On 27 June 1920 the sesquicentennial of the birth of Lazare Hoche was to be marked in Versailles. Hoche, born in 1768, was the French revolutionary general who had commanded the abortive invasion fleet that was supposed to land in Bantry Bay in 1796 in support of the United Irishmen; the anniversary celebration had been delayed by two years owing to the war. MacWhite recalled that he and George Gavan Duffy visited the mayor of Versailles to explain Hoche’s Irish connection. The mayor was happy for them to take part in the ceremony, though he had to be discreet, and they agreed to present a bronze palm, embellished with the Irish and French tricolours and engraved ‘Hommage de l-Irlande reconnaissante 1796–1920’, as part of the official wreath-laying.

The commemoration was quite elaborate, with a viewing platform erected in front of the statue of Hoche in Place Hoche that was to be the venue for a military parade. MacWhite’s uniform came in handy; he slipped into the parade wearing both it and his full decorations and was seemingly mistaken for an official representative of the Foreign Legion. He laid the palm, saluted before it, saluted the dignitaries on the platform, and slipped away as the Marseillaise was being played. The palm stood out amongst the wreaths and attracted attention, not least from the British military attaché, resulting in a complaint from the British embassy, a reprimand for the mayor and at least one newspaper report in New York. Upon inquiring after its whereabouts in 1957, MacWhite was informed that the palm itself was still held in the Musée Lambinet in Versailles—a tangible remnant of the unofficial diplomacy on which he had embarked at the start of his lengthy career.

The Michael MacWhite papers are retained in the UCD Archives and can be viewed subject to permission. Applications should be made in writing to UCD Archives, University College Dublin, James Joyce Library, Belfield, Dublin 4, https://www.ucd.ie/archives/.

John Gibney is DFAT 100 Project Co-ordinator with the Royal Irish Academy’s Documents on Irish Foreign Policy project.

FURTHER READING

J. Gibney, M. Kennedy & K. O’Malley, Representing Ireland: 100 years of Irish foreign policy, 1919–2019 (Dublin, 2019).