Michael Collins’s ‘secret service unit’ in the trade union movement

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2014), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 22

Michael Collins—in the autumn of 1919 he set up a ‘secret service unit’ in Dublin with the aim of securing key positions in the Irish trade union movement for committed separatists.

‘I was a member of an intelligence or secret service unit under the control of the chief intelligence officer, the late Michael Collins. This Dublin unit was under the direction of Martin Conlon. What was called the Labour Board was formed under this unit; and about the autumn of 1919, I was detailed for special duty on this Labour Board by orders of the Army Council.

‘Our duty was to use our influence in our various trade unions, and in the Labour movement generally, on behalf of the Republic; to get hold of men in important key positions, such as power stations, railways, and transport dockworkers, etc.; and most important of all, to undermine the amalgamated and cross-channel unions, and where possible to organise a breakaway from these unions, and establish purely Irish unions instead, manned and controlled by men with republican and national tendencies; in other words we were republican agents within the trade union movement. This was regarded as very important work both by the Army Council and the Dáil at the time.

‘We were in direct communication with Michael Collins, both as minister for finance and chief intelligence officer of the Army, and on different occasions were supplied with financial assistance to carry on the work. As members of the IRA our work was directed on those lines, and under orders the same as ordinary members though more rigidly controlled. We worked under active service conditions, and our company officers were instructed to excuse us from ordinary parades, while still retaining us on the roll of the company, and were thus liable for mobilisation at any time.’

Applicants submitting this statement included Thomas Maguire of the Stationary Engine Drivers society (SED) and Joseph Toomey (WMSP/34/REF/2175), the district delegate of the British-based Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE), the largest British craft union. Martin Conlon (W24SP10720), the man put in charge of this unit, was a Dublin sanitary officer rather than a union activist but he was also on the IRB supreme council, as was his deputy, Luke Kennedy (W24B860), an electrician.

The ‘Labour Board’

Thomas Maguire of the Stationary Engine Drivers society, and a member of Collins’s ‘Labour Board’ unit, who submitted a pension application. (Bill McCamley)

The unit was given the cover name of ‘Labour Board’ and established at an IRB meeting chaired by Collins’s financial confidant Joe McGrath TD. Besides Conlon being appointed as chairman, another IRB man and senior Volunteer officer, Patrick McGurk, was appointed secretary. The Board quickly recruited a provisional committee from craft union activists in the Irish Volunteers, Sinn Féin and the Irish Citizen Army to establish the new union. Official negotiations between this wider committee and Dáil Éireann took place with Countess Markievicz as minister for labour and the secretary of her department, Diarmaid Ó hEigeartaigh, another IRB man.

On Sunday 9 May 1920 these efforts bore fruit when a packed meeting of craft workers was held in the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, to establish the Irish Engineering, Shipbuilding and Foundry Workers Trade Union (IES&FTU). It recruited the aristocracy of labour and by the end of the year had 4,500 members. The once-dominant British-based ASE had shrunk to 1,762 members in what would become the Irish Free State. As Kennedy put it bluntly in his pension application, ‘We smashed up most of the English trades unions in Ireland at that time’. Things were different north of the border. The IES&FTU made no inroads in Northern Ireland.

Funding

One of the mysteries of the IES&FTU in its early days was how it was funded. The deeds on the premises occupied by the SED at 10 Lower Abbey Street were provided as collateral for a mortgage on the IES&FTU’s new offices at 6 Gardiner Place (where its successor, the TEEU, still resides). By coincidence, another tenant in Abbey Street was George Moreland Cabinet Makers, a front for Michael Collins’s ‘squad’. Once Collins died at Béal na mBláth in August 1922 the only person who might have shed light on the subject was Joe McGrath, but he never divulged details of Collins’s myriad financial transactions. His role in the finances of the Republic are worthy of closer attention. Dismissed by the accountancy firm of Craig Gardner for participating in the Easter Rising, he was recruited as finance officer by the Irish Transport and General Workers, an ideal position for laundering other funds. By 1923 he was the new state’s minister for industry and commerce, as well as one of its leading businessmen.

In his pension application Luke Kennedy states that the ITGWU ‘was not very favourable to us at all. As a matter of fact from the start of our union they accused us of being a political union and do so still.’ The record suggests otherwise, with the ITGWU playing a leading role in having the IES&FTU accepted into the Irish Trade Union Congress and Labour Party and working closely with it in the engineering strike of 1921. In fact, the most striking feature of the IES&FTU was its lack of politics beyond a simple desire to ‘smash up’ British rivals. It soon fell prey to the splits and demarcation disputes that plagued craft unions at the time. But its birth is indicative of Collins’s extraordinary ability to control and manipulate any group he saw as either a threat or a potential asset to his objectives.

1916 Rising

Records and documents relating to Easter Week 1916 are contained in a series of files catalogued under ‘Membership and Organization’, including IRA Nominal Rolls and reports by Cumann na mBan, Na Fianna Éireann and the Irish Citizen Army. The most important of these files include the ‘Nominal Rolls for Easter Week 1916’ compiled by all five Dublin battalions of the Irish Volunteers, the Citizen Army and Cumann na mBan; details of the Rising outside Dublin are covered in ‘Brigade Activity Reports’ for Galway, Louth/Meath and Wexford. While the brigade and battalion reports for Dublin consist largely of lists of participants, the level of detail provided by the senior veterans is disappointing, with varying degrees of effort employed in providing the full names and addresses of participants and precise details of organisational structures. The brigade reports from the country districts that participated in the Rising are more detailed and include the texts of cross-examinations of the oral testimony of senior veterans and precise details of the activities of the Volunteers in Galway, Louth/Meath and Wexford.

‘Saved the name of Tipperary’

Volunteer Michael O’Callaghan of Tipperary was responsible for one of the most obscure incidents of the 1916 Rising. O’Callaghan was on the run from police when he shot dead two RIC men, Thomas Rourke and John Hurley, who entered a house in which he had been hiding out during Easter Week on the Limerick border. O’Callaghan’s pension file (MSP/34/REF/4189) reveals that after months on the run he escaped to New York, where he became involved in an ill-fated attempt to ship guns to the Volunteers and was jailed pending extradition. He returned to Ireland in 1923 and became a district court clerk and subsequently a creamery manager. In support of O’Callaghan’s claim for a pension, senior veteran and IRA legend Dan Breen told the Military Service Pensions Board that O’Callaghan had ‘saved the name of Tipperary by his actions during that famous week’, adding that ‘I only wish we had some more like O’Callaghan, [and] 1916 would not have faded out as it did’.

‘Threatened’ to return home

Volunteer Francis Teeling was shot and captured by the Crown forces for his role in Bloody Sunday, 21 November 1920, when Michael Collins organised the execution of thirteen British agents across Dublin. Teeling managed to escape from Kilmainham Gaol in March 1921, subsequently took the Free State side in the Civil War and was wounded in action for a second time while serving in Munster. Teeling’s pension file (MSPC/24/SP/913), however, reveals a darker aspect to his life; in April 1923 he was dismissed with ignominy from the National Army after killing William Johnston (a member of the Citizens’ Defence Force) in the bar of the Theatre Royal on 27 March. Released from jail after a sentence of less than two years, Teeling adopted a pseudonym and emigrated to Montreal. His successful application reveals that he ‘threatened’ to return home if not awarded a pension, prompting General Richard Mulcahy to endorse the award, as ‘[Teeling] had publicly misconducted himself in such a way on a number of occasions as to run the danger of bringing serious discredit to us’.

IRA membership rolls

The IRA membership rolls provide details of the membership and organisational structure of the sixteen divisions of the IRA, constituting a total of 87 brigades, on two crucial dates—11 July 1921 and 1 July 1922. Comprising a total of 49,982 individual documents, these files were collated around 1935 and the key dates employed by the board will allow researchers to analyse the changing nature of the organisation in the crucial period between the Truce and the commencement of the Civil War.

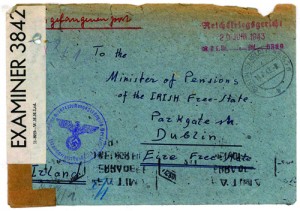

Envelope containing a letter (29 June 1943) from William Coman informing the pension authorities in Ireland that he was now a POW in Nazi Germany and that he would ‘have to leave my money with you until the war is over’. He had joined the British Army as a sixteen-year-old in 1916, was sentenced to fifteen years’ imprisonment for his part in the Connaught Rangers mutiny in India in 1920, was released in January 1923 and re-enlisted in the British Army during World War II. A second letter (25 May 1945) informed them that he had been repatriated from Germany and asked them to forward the arrears. (Military Archives)

Belfast pogroms

The level of detail in the reports varies; some include the activities of Crown forces and document the fearsome levels of violence in certain parts of the country. The report of the 3rd Northern Division (Files RO 402–406A), encompassing Belfast, Antrim and Down, underlines the frightening level of sectarian violence facing the Catholic community in Belfast and contains the following entries: 21 July 1920, Belfast Catholics chased from shipyards; 22 July 1920, military fire on crowd on Cupar Street, three killed; 23 July 1920, Clonard [monastery] lay brother shot dead and 200 wounded; 18–21 April 1922, onslaught on Marrowbone [district of Ardoyne], Annie McAuly, James Parron, Glenpark Street, Denis Diamond, 19 Vulcan Street, killed, John Walker, Short Strand, killed, and Andrew McCourteny, Dagmar Street, killed (MA/MSPC/RO/401).

Conclusion

The release of these files will not force a radical reconsideration of the overall narrative of the Irish revolution; it will, however, make future research more reliable, infinitely more detailed and decidedly more interesting. The nature of the precise details contained in these reports complements the more expansive personal narratives contained in the Bureau of Military History Witness Statements and made available to the public in 2003. Upon exploring this collection, presented in an accessible and user-friendly fashion, any frustration one might have felt at the length of time it has taken for this information to be released evaporates. This is a monumental achievement by Military Archives and those involved deserve the very highest of plaudits. The history of the Irish Revolution has truly been democratised and the capacity of academics and non-academics alike to explore the Independence struggle has been transformed.

Padraig Yeates is the author of City in turmoil: Dublin 1919–1921 (Gill & Macmillan, 2012).

Conor McNamara is the co-author of Easter 1916: a research guide, to be published by Four Courts Press later this year.

Further reading

P. Yeates, ‘Craft workers during the Irish Revolution, 1919–1922’, Saothar 33 (2008), 37–56.

C. Crowe (ed.), Guide to the Military Service (1916–1923) Pensions Collection (2012).