Meet the parents

Published in Features, Issue 4 (Jul/Aug 2008), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 16

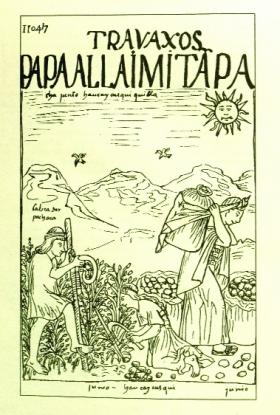

Seventeenth-century print of potato-harvesting in the Andes. (Det Kongelige Bibliotek, København)

If the modern domesticated potato were to return to the Andes to seek out its roots (sic), it might find itself in company as alien and unrecognisable as the Irish-American who visits deepest Kerry in search of long-lost kin. The fresh-faced, pale and uninteresting new potato would consider its South American relations alarmingly odd—some purple-skinned, others black and shaggy; some small, splotchy and bulbous, still others long and coiled, looking more like a section of large intestine than an accompaniment to the Sunday roast. Our refined potato, whose experience heretofore was limited to the Roosters and Pinks of the Tesco veg section, would be further baffled by the names of these thousands of new-found cousins—waka qallu (‘cow’s tongue’), quwi sullu (‘guinea pig fetus’), puka pepino (‘red cucumber’) and papa Ilunchuy waqachi (‘the weeping bride’). Most overwhelming of all, perhaps, would be the introduction of our latter-day spud to his great-great-grandparents—toxic, tiny, wizened things, with deep-set eyes and a fondness for oxygen-starved altitudes. At this point our potato might decide, along with our American visitor, that seeking after origins is a disappointing, disturbing business.

Cultivation perfected by the Inca

The cultivation of the potato over 8,000 years ago by the Quechua Indians, sturdy forebears of the Inca, marks the shift from nomadic to settled culture in South America, and it was in large part the potato (with a little help from the llama) that allowed them to stop hunting and gathering and put down roots in the shallow mountain soil. They created special tools for ploughing the fields and digging the potatoes—the taclla and the ayacho. They turned the potato into flour and freeze-dried chunks (called chuno) for long storage and insurance against famine and drought. And they made potato beer called chichi, and their version of poteen called chakta. The potato and this highland community grew up together, each one cultivating and refining the other. It is to these people that the potato owes its discovery, domestication and eventual domination of the globe; it is to the potato that the Andean people owe their survival and their way of life. The Inca perfected the cultivation of the potato—reclaiming land, building intricate terraces and irrigation systems on the mountainsides, selecting and nurturing the plants best suited to particular climates, mastering food storage and distribution, and inventing a system of community labour (mita). And it was this steady source of food that allowed the Inca to concentrate on other matters—like art, religion, architecture and expanding their empire.

Central place in mythology

No wonder, then, that the earliest myths of this civilisation involve the exploits of Huatya Curi, the legendary mountain man whose name means ‘Potato Eater’. Humble and ragged, the son of the cold mountain wind, Potato Eater rises from obscurity to become a great chief who unites the Andean people. He might be taken as a personification of the potato itself—dusty and unpromising on the outside, but containing a hidden strength. (As you would expect of a superhero created by a tuber-centred culture, Potato Eater’s superpowers include his ability to resist the cold and to see in the dark.) Central, too, in this mythology is Axomama, or Potato Mother, the source of life. For the modern, post-Monty Python subject, there is something almost comical about the notion of the humdrum potato as a portal to the sacred. We tend not to look for our inner chi in a bag of chips, or treat our Taytos with any creaturely deference. But in the Andean universe the potato belongs to the Uku Pacha, the mysterious inner world—‘a place’, writes Luis Millones, ‘of seeds and corpses’. This mystical realm contains the secrets of past and future, birth and death. Nowhere, perhaps, is this intimate connection between potato and person more manifest than in the pottery of the Moche people, who ruled the northern coastal regions of Peru in the pre-Inca period. In some of their extraordinary ceramic art, human body parts erupt from the eyes of potatoes, suggesting our genesis in Potato Mother. In others, anthropomorphic potatoes seem on the verge of translating into human form. While anthropologists continue to debate the significance of Moche pottery, we might take these original Mr Potato Heads as emblematic of the place of the potato in human history—so bound up is one with the other that it is difficult to know where one ends and the other begins.

This was certainly the impression made on early Spanish explorers of South America, who returned with stories of blood sacrifice rituals practised to ensure a plentiful potato crop: from southern Ecuador came rumours of the annual sacrifice of 100 children during the harvest festival; from Peru, tales of farmers spreading human blood over potato fields. There were stories, too, of women using chuno to mop up blood in the aftermath of hacienda feuds, and greedily devouring the blood-soaked cakes. Spanish priests worried about the almost Eucharistic place of the potato in Incan culture, with its dangerous co-mingling of human and potato flesh—an association made seemingly more sinister by the blood-red flesh of some varieties of Andean tubers.

Beyond the perhaps hyperbolic accounts of missionaries, however, historical records witness to a deep-rooted link between the potato and human suffering. The Inca Empire crumbled under the Spanish conquest, and the subsequent enslavement of the indigenous population was largely dependent on the potato. While the first Spanish explorers thought the potato a dainty truffle, this reliable foodstuff soon became the food of slaves. Thousands of potato-eating natives were worked to death in the silver and mercury mines at Potosi and Huancavelica, digging up the treasure that would sustain the Spanish Empire and bankroll the European economy. This was the first time, but would not be the last, that the potato allowed the creation of a well-fed underclass whose labour would prop up a ruling élite, for along with silver and gold the Spanish returned to Europe (and Ireland) with another buried treasure—the potato.

Willa Murphy is Lecturer in Irish Writing at the Academy for Irish Cultural Heritages, University of Ulster.

Further reading:

L. Millones, The potato, treasure of the Andes: from agriculture to culture (Lima, 2001).

C. M. Ochoa, The potatoes of South America: Bolivia (trans. Donald Ugent) (Cambridge, 1990).

J. Reader, Propitious esculent: the potato in world history (London, 2008).

R. N. Salaman, The history and social influence of the potato (Cambridge, 1949).