Medieval Scotland & Ireland: overcoming the amnesia

Published in Features, Gaelic Ireland, Issue 3 (Autumn 1999), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 7

The statue of Robert Bruce at Bannockburn. (Michael Cyprien)

There is one overriding and rather obvious dissimilarity between Ireland and Scotland: Ireland is an island. Throughout its early history, at least until the arrival of the Vikings at the end of the eighth century, Ireland was inhabited by a people who spoke a common language and who thereby could convince themselves that they were one nation: they were the Gaídil, and their language was the language of the Gaídil, and took its name from them, Goídelc (Gaeilge in Modern Irish). This made the island’s inhabitants very sensitive to new arrivals and their distinctiveness: the indigenous inhabitants were always the Gaídil, and the newcomers, no matter how long they had been in Ireland, were always the Gaill. So, in Ireland there never emerged, at any stage in the Middle Ages, a willingness to accept foreigners and to offer them, as it were, membership of the Irish nation.

Exclusivity versus inclusivity

In contrast, that part of northern Britain that became Scotland found it much harder to be exclusive, since it was only part of an island and was surrounded to north and west by many others. Foreigners who settled in Scotland could very quickly (within the space of a generation or two) become Scots. Thus, although there was a massive programme of Anglo-Norman settlement in both Ireland and Scotland in the twelfth century and later, in Ireland those Anglo-Normans remained a separate nation to the Irish, whereas in Scotland they became part of the Scots nation. The latter did not become ‘the English of the land of Scotland’ as their counterparts in Ireland became ‘the English of the land of Ireland’.

Instead, they came to see themselves as every bit as Scottish as the people they found there on their arrival, and Scotland and Scottishness—the Scots identity—adapted itself to make room for them. Hence, for instance, the Irish wrote a famous Remonstrance to the Pope in 1317 saying that they were so different from the English of Ireland in language and customs that there could never be peace between them, whereas three years later the Scots sent to the Pope their famous Declaration of Arbroath in which they boasted of their ancestral triumphs over the Britons, the Picts, the Angles, the Norwegians and the Danes, and yet many of the men who signed this letter were the grandsons and great-grandsons of men who had migrated, usually via England, from Normandy, Brittany and Flanders, and only settled in Scotland in the quite recent past! The fact that they now believed that they were Scots, part of a nation that had inhabited the northern part of Britain since the dawn of history, only goes to prove that, unlike Irishness, Scottishness was not an exclusive club; membership was wide open, and it was that openness, that receptiveness, that adaptability, which contributed to the emergence of Scotland as a well-respected monarchy on the western European model, from the twelfth century onwards.

Scotland’s multi-ethnic society

Thus, medieval Scotland was, as Ireland was not, a multi-ethnic society, with a very heterogeneous mix long before a single Anglo-Norman set foot in it. In Caithness, Argyll, and the Western Isles there was a strong Scandinavian input as a result of settlement in the Viking era. Stretching south from Dumbarton on the Firth of Clyde to the Lake District in north-west England were the people of the ancient kingdom of Cumbria or Strathclyde, who were predominantly Brittonic or British, related, in other words, to the people of Wales. They were matched on the east coast by the northern part of the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria, usually called Lothian, which provides the very important English element in the mix.

Early eleventh-century Scotland. (Matthew Stout)

To the north, lay people descended from the Picts, but now fully subsumed into the Gaelic social order, which had been imposed on northern Britain as a result of the Dalriadic invasion from Ireland. By the time that Scotland truly emerges into the pages of history, that Gaelic culture was supreme and gave the land its very name, Scotia, the land of the Scotti, the original preferred Latin name for the Irish. So, whilst there may be quite stark differences between Scotland and Ireland in the Middle Ages, there is no escaping this one overriding link. The Irish and the Scots (that’s to say, the dominant political élite within what we call Scotland) traced their ancestry back to a common origin. They were, taken to its logical extreme, of the same nation.

The Scots’ Irish origins ignored

With few exceptions, historians of medieval Scotland have paid little more than lip-service to this most fundamental of facts. What is worse, they have even ignored it. To take one example: in 1965, the great Scottish medievalist Geoffrey. Barrow produced his classic biography of Robert Bruce, which contains his translation of a Latin letter probably sent by Robert Bruce to Ireland:

The king sends greetings to all the kings of Ireland, to the prelates and clergy, and to the inhabitants of all Ireland, his friends. Whereas we and you and our people and your people, free since ancient times, share the same national ancestry and are urged to come together more eagerly and joyfully in friendship by a common language and by common custom, we have sent over to you our beloved kinsmen, the bearers of this letter, to negotiate with you in our name about permanently strengthening and maintaining inviolate the special friendship between us and you so that with God’s will your nation may be able to recover her ancient liberty…

Professor Barrow translated the letter thus, in spite of the fact that the original text did not contain the phrase vestra nacio, but rather nostra nacio, ‘our nation’. Robert Bruce wrote seeking an alliance with the Irish so that ‘our nation’, the Scots and Irish nation, might be able to recover her ancient freedom.

One should say that in a subsequent edition Professor Barrow amended his translation so that it now does indeed read ‘our nation’, but one can’t help but feel that his original decision to translate this phrase the way he did—in effect, to assume that it contained a scribal error—stemmed from an inability or unwillingness to accept that a man like Robert Bruce, a Scot in the fourteenth century (other than perhaps an inhabitant of the Highlands and Islands) might regard himself or seek to pass himself off as of the same nation as the Irish. And yet, this is something which we must accept, and is indeed happening: a younger generation of Scottish historians has emerged who are much more open to the Irish dimension in Scottish history, and are reminding us that medieval Scots, and their kings, were indeed conscious of their Irish links, whether in a strictly ethnic sense in the form of genealogies and king-lists which linked them into the Irish chain of descent, or in the broader cultural, social, and ecclesiastical sense with which we are more familiar.

Writing history backwards

This has been a very positive development, because it has helped to a certain extent to free us from the shackles of hindsight. Because Scotland has had a constitutional link with England for the last four centuries, there is something of a tendency to write its history as if that had always been the case, or had always been inevitable, and to focus historical writing on examining how it came to be. This is useful to the extent that part of the purpose of history is to help us understand how things came to be the way they are. It is not helpful, and is rather disingenuous, if it involves airbrushing the picture to remove those images which might have suggested a different story. If the story that is to be told is of the emergence of a distinct kingdom of the Scots, the development of the Scottish monarchy and parliament, and eventual union of both crown and parliament with England, then there are going to be a lot of red herrings lying around. And Ireland will be one of them. Eyes will be firmly focused on Scotland’s frontier to the south, not on the damp and misty west, and telling the story of Scotland’s relationship with Ireland in the Middle Ages is not going to be part of the ‘enterprise’ of Scottish historiography.

Late thirteenth-century woodcut of Edward I of England, Bruce’s great rival.

A similar situation pertains in Ireland, where the historiography of the country from the twelfth century onwards is dominated by discussion of Anglo-Irish relations. Thus, the book shelves and the academic journals in both countries are packed with works on Anglo-Scottish relations and on Anglo-Irish relations in the Middle Ages, but the story of Scotland’s connection with Ireland in this period still remains largely untold. This is not because there is very little to say on the subject, and neither can it be because it was not viewed as important in its own day. The shelves remain empty and the story remains untold, because we do not regard it as important.

Another example of this springs to mind. It’s a crude test, but there may be some lesson to draw from it. Again, it involves Robert Bruce and Geoffrey Barrow, though it is by no means intended as a criticism of the latter, whose work one cannot but admire. Bruce died in 1329 but did not find himself a biographer as such for another half-century, when John Barbour, archdeacon of Aberdeen, wrote his epic poem The Bruce. As it has come down to us, this fourteenth-century metrical biography has 13,645 lines. From an Irish point of view, one of the most remarkable things about Bruce’s career is his decision, not long after his great victory at Bannockburn, to launch an invasion of Ireland, led by his brother Edward, who was set up as king here. Archdeacon Barbour obviously thought this important too, because he devoted a full 1,407 lines to it, over 10 per cent of his poem. Yet Professor Barrow’s 446 page biography of Bruce devotes only one paragraph to the Irish invasion.

Again, it must be stressed that this is not a criticism of Geoffrey Barrow. He was not being a ‘bad historian’ in relegating the Irish aspect of Bruce’s career to this position; but he was being a man of his time. In the 1370s, when Archdeacon Barbour was writing, the affairs of Ireland and Scotland were quite closely entwined. They had been even more closely entwined earlier, but Barbour was not to know that they were now inexorably drifting apart. He just told it as he saw it, and gave Ireland the coverage he thought it deserved. The plans which the Scots had for Ireland a generation or two earlier still seemed important, even though Edward Bruce had been killed in battle there, and the Scottish kingship of Ireland had died with him. Barbour was, it seems, simply expressing a contemporary belief that Scottish involvement in Ireland in the time of Robert Bruce was relevant, and not an aberration from the main story of Scotland. By the mid-1960s, things looked very different. No one can deny that Ireland and Scotland had indeed drifted very far apart in the intervening centuries. Ireland had come to occupy a very peripheral role in Scottish affairs, and anyone writing about Robert Bruce, and trying to assess his contribution to Scottish history, would not spill too much ink on waxing lyrical about his Hibernophilia.

A new Scots-Irish awareness

Well, that was the 1960s, and that was acceptable then. But something has happened since. Whatever the reason—perhaps a growing sense of being or of wanting to be more distinctively Scottish—the fact is that work produced in recent years on the history of medieval Scotland seems to be less preoccupied with England. Other neglected aspects of Scottish life in the Middle Ages are getting the attention they deserve, and Scottish links with places besides England are being investigated, whether it be trading contacts with the North Sea ports, the whole Scandinavian world to which much of Scotland and the Isles belonged since the Viking Age, and links with Ireland which reach back further still. In Scotland today, therefore, there is a growing interest in Ireland; or so it seems. But why? Could it be that, as Scots have gone in pursuit of their Scottishness, their search has brought them to Ireland, that the Scottish historian who tries to understand what made medieval Scotland ‘tick’ is driven to the conclusion that, perhaps, in the past, we have underestimated the significance of the Gaelic component in that society?

‘Stemming from one seed of birth’

One wouldn’t want to make too much of this point, since by the reign of Robert Bruce its Gaelic inheritance was no longer at the very heart of the Scots nation. But nonetheless a vital ingredient in the dynamic of Scottish society continued to be supplied by Ireland. That is what Robert Bruce meant when he spoke of the Scots and Irish sharing ‘the same national ancestry’, or, to give a more direct translation, ‘stemming from one seed of birth’. Now, one is tempted to take that with a pinch of salt, and it can be argued that Robert had quite a nerve talking in such terms since the Bruces were of Anglo-Norman extraction, though he did have Gaelic ancestry on his mother’s side. Furthermore, when Ó Néill of Ulster wrote to the pope during the course of Edward Bruce’s invasion, explaining why he supported the Scots’ attempt to overthrow English rule, he said of the English that

in order to shake off the harsh and insufferable yoke of servitude to them and to recover our native freedom which for the time being we have lost through them…we call to our help and assistance the illustrious Edward Bruce, earl of Carrick, brother of the lord Robert, by the grace of God the most illustrious king of Scots, and sprung from our noblest ancestors.

Therefore, in this period we are not simply dealing with the Bruces manipulating Irish dissidence for their own ends, by exploiting some vague memories of ancestral links with Ireland; we have perhaps the most powerful king in Ireland trying to convince the outside world that Edward Bruce was more entitled to rule the Irish than Edward II because he was ‘sprung from our noblest ancestors’, clearly as part of an attempt to harness the shared background of the Scots and Irish in a campaign against their common enemy, England. And it is that shared Gaelic inheritance that produced the Bruce invasion of Ireland.

The Bruce invasion in context

In a recent paper on this subject, another giant of Scottish historiography, A.A.M. Duncan, stated his conclusion that the invasion is ‘an expedition which cannot be explained by a close or continuous inter-relationship of Irish and Scottish families or politics’, but, however much one respects Professor Duncan’s work, I would contend that the Bruce invasion cannot be explained by any means other than a close and continuous inter-relationship between Irish and Scottish families and politics.

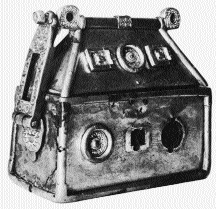

The Monymusk Reliquery, a seventh-century casket that originally contained relics of Columba, was traditionally borne before the Scots in battle. The Abbot of Arbroath carried it at Bannockburn. (National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland)

To prove the case to the contrary involves an examination of the politics of the north Irish Sea area over a lengthy time-span, and of the relationships between families with connections on both sides of the North Channel over a similar time-span, an exercise which will have to await another occasion.

But where, clearly, we have been going wrong, in examining events in the Irish Sea world of which the Bruce invasion is simply one of the most dramatic and best-documented, is in our refusal to view them in a sufficiently long-term context. Over the centuries really extraordinary things happened that involved men from Ireland in Scotland and men from Scotland in Ireland. Each, however, has tended to be looked at in isolation, and has therefore given the appearance of happening out of the blue, so that it has been impossible to build up a contextual framework for them. Hence, the result is that they are ignored, or relegated to the realm of anecdote, or just explained away as once-off random eccentricities of the Celtic world. However, a long-term study of the subject, even if it did not explain each incident fully, would make it possible to fit such occurrences into a long-standing pattern.

A Scots-Irish realignment

There is, though, one way in which the events of Robert Bruce’s reign do mark a change and do not, therefore, fit into an earlier pattern. Professor Rees Davies recently published an important set of essays, Domination and Conquest. The Experience of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, 1100-1300, in which he analyses the way in which, the English kings gained an ever-increasing dominance over the other peoples inhabiting these islands. It’s a very persuasive argument which brings out extremely well the similarities in the experience of the Scots, Irish and Welsh at English hands, and the gradual intensification of English overlordship over each. But for much of the time (and Professor Davies admits as much himself), in trying to treat of the affairs and experience of Scotland in the same breath as Ireland and Wales, one gets the feeling that one is pushing a square peg into a round hole. The reason is that Ireland and Wales had very similar experiences of Anglo-Norman aggression—in the case of the Welsh, it came a century before the Irish, shortly after 1066—including dispossession, colonisation, denial of access to the law, erosion of the power of the native rulers, and ultimately the assertion of English lordship over both countries.

However, at the same time in Scotland something very different was happening. Unlike Ireland and Wales, Scotland had only one king, and far from being invaded by Normans, he was inviting them in, using them as instruments in the assertion and expansion of his own royal authority. So when the Anglo-Normans invaded Ireland, the Scots, at least the Scots nobility many of whom had good Anglo-Norman pedigrees, felt no great sympathy for the native rulers whose lands were removed and power eroded. Their sympathies, in fact, lay full square with the invaders, the contemporary Melrose chronicle, for instance, pointing out proudly that their leader Strongbow was a first-cousin of the Scottish king! And when Edward I conquered Wales in the early 1280s, Alexander III was still comfortably on the Scottish throne, and there is no reason to think that he felt any unease at this development. However, twelve years later when Alexander was dead and his direct royal line extinct, the Scots found themselves in a very different position, facing war with England, and an attempt by Edward I to repeat there his earlier success in Wales.

It is at this point that a major sea-change takes place in the affairs and attitudes of the Scots. They very quickly found that hand in hand with a campaign of opposition to the king of England went the attempt to foment trouble for him elsewhere. The Welsh, in the past, had been able to benefit from sympathetic outbursts of rebellion across the Irish Sea, because they themselves were free of ties with the Anglo-Norman colonists there, and in many cases, as already noted, suffered at their hands in the same way that the native Irish did. The problem for the Scots, when their breakdown in relations with the English occurred, was that they could not make such ready recourse to Irish support, since they themselves were products of the Anglo-Norman world, and their ties and sympathies had lain hitherto with the colonial community in Ireland.

Rediscovering lost links

Thus, here we find one of the most remarkable consequences of the rupture with England that took place in the 1290s, and that is that the Scots—and most spectacularly in the case of the Bruces—in trying to sow the seeds of trouble for the domineering Edward I and for his weak son and successor Edward II, were forced into the camp of the native Irish—and forced, in some respects, to re-discover or re-invent their identity, including their links with their ancestral homeland.

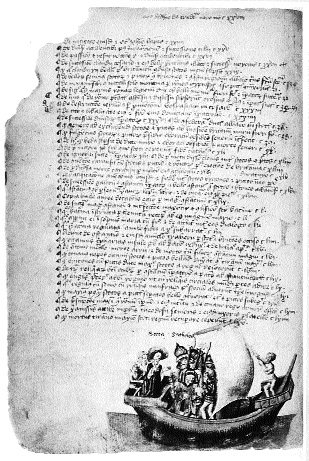

The illustration at the bottom of this page from Walter Bower’s Scotichronicon (c. 1440) shows the legendary Scota, daughter of Pharaoh (after whom Ireland, and later Scotland, were supposed to have been named), sailing westwards from Egypt with her husband Gaythelos, believed to have invented the Gaelic language! (Corpus Christi College, Cambridge)

Looking at Scotland over the recent past, it occurs to one that there was more than a bit of Edward I about Margaret Thatcher. John Major, on the other hand, had Edward II written all over him. It is interesting, therefore, that it was during this recent period that we have witnessed such a swell of enthusiasm for Scottish independence, and one cannot help but wonder to what extent those two English leaders’ eighteen years or so of not entirely unchallenged rule over Scotland, like that of the first two Edwards, contributed to Scotland’s rediscovery of itself, its Scottishness, and, in some small respect, its Irishness.

Seán Duffy is a lecturer in the Department of Medieval History, Trinity College Dublin.

Further reading:

S. Duffy, ‘The Anglo-Norman Era in Scotland & Ireland: convergence and divergence’ in T.M. Devine (ed.), Celebrating Columba: Irish-Scottish connections, 597-1997 (Edinburgh 1999).