Iona, the Vikings and the making of the Book of Kells

Published in Features, Issue 3 May/June2013, Medieval History (pre-1500), Vikings, Volume 21

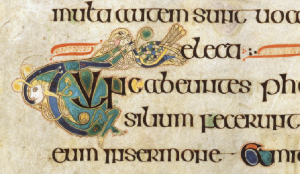

It has been suggested that this Chi-Rho initial, with its dazzling range of colour and intricate patterns, would have taken months, perhaps even a year, to complete. This is the top left corner of the folio, with two moths and an angel enmeshed in a sequence of curvilinear designs. It represents a mere 10% of the page as a whole. Time was obviously not of major concern to the artists, as suggested by the cartoon

Despite more than a century of scholarly research, we know remarkably little about the circumstances in which the Book of Kells was made. While it is now clear that at least four scribe-artists were involved, their identities remain a mystery, as do their status and the nature of their training. Likewise unknown is the identity of the patron and the specific events that prompted the undertaking of such an ambitious work. While it is generally accepted that the book was begun in the monastery of Iona at some point after c. 740, the precise date is far from clear. Many years ago the art historian Françoise Henry made the intriguing suggestion that it may have been commissioned to mark the 200th anniversary in 797 of the death of St Columba, the founder of the monastery; whether true or not, popular opinion appears to favour a date in the years around 800, with some commentators adding a gloss to the effect that the manuscript was subsequently finished at Kells. These oft-repeated assertions have not been sufficiently challenged in recent years, despite the fact that the period around 800 remains a most unlikely time for the start of such a project. There is also the mystery of the unfinished folios, for which no satisfactory explanation has been offered. There are many further anomalies, the most conspicuous of which is the chaotic insertion of numbers in the canon tables—‘unbelievably irresponsible’, in the words of Françoise Henry. The making of the manuscript was clearly not the result of a smooth, orderly process; within the scriptorium (or scriptoria) there were obviously occasions when things went badly wrong. This gives rise to a further issue: for how long did work continue on the decoration of the book? We simply do not know whether the illumination was carried out in a relatively short space of time, perhaps two or three years, or whether the process was far slower, stretching across decades rather than years.

Artistic evidence

![from The New Yorker. (The Book of Kells, folio 34r [detail], the ‘Chi-Rho’ Initial, © The Board of Trinity College Dublin 2013)](https://www.historyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/8.png)

from The New Yorker. (The Book of Kells, folio 34r [detail], the ‘Chi-Rho’ Initial, © The Board of Trinity College Dublin 2013)

The second feature to note are the displays of ingenuity, both artistic and intellectual, intended, it seems, as conscious witticisms, as if the artists were showing off to their peers. There is a need for caution in this regard, however, because we cannot be sure what made people laugh or smile in the distant past and we are not accustomed to seeing ancient monasteries as fun-loving places. In recent years there have been interesting studies of medieval humour and it is clear that it would be a huge mistake to imagine that Irish monks of the eighth century were incapable of laughter or amusement. Indeed, Irish scholars are well known for their verbal and intellectual dexterities, seen especially in the creation of riddles and witty verbal games. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín has drawn attention to witticisms attributed to Cú Chuimne, one of the Iona monks:

Cú Chuimne in youth

read his way through half the truth.

He let the other half lie

while he gave women a try.

Above: It would be a huge mistake to imagine that Irish monks of the eighth century were incapable of laughter or amusement. In this case an initial T is formed by an elasticated man, who lethargically stretches out his arms to catch a passing bird, evidently a peacock. The passage (from St Matthew’s Gospel) describes how the Pharisees took council as to how they might ensnare or seize Christ. As the peacock was seen as a symbol of Christ, this is a witty response to the words of the text. (The Book of Kells, folio 96r, © The Board of Trinity College Dublin 2013)

The dazzling range of colour and the time expended on the painting, along with the humour, suggest that the Book of Kells was produced in a monastery at ease with itself, where the immediate future was reasonably secure. It was clearly a well-established monastery, with a well-stocked library and a highly professional scriptorium. This all points to Iona rather than Kells, a provenance that most scholars now accept. The production of such a highly ornamented gospel-book was an enormous task, one that was surely beyond the means of a new monastery like Kells in the first years of its existence. And the character of the art itself points to a date well before 804–7, when Kells was established.

Columba’s anniversary?

We have already noted one event that might have stimulated the making of a splendid gospel-book: the 200th anniversary of the death of Columba. But if the book was to be ready for a specific occasion, a high degree of forward planning would have been required, and herein lies a problem: it is hard—if not impossible—to imagine such an extravagant and time-consuming work as Kells being made against a deadline. On the other hand, there is no doubt about the association with Columba, since the Annals of Ulster in 1007 described the book as ‘the great gospel of Colum Cille’ and ‘the most precious object of the western world’. By then, if not long before, it was being treated as part of the minna or treasured relics of the saint. Several scholars have argued that the idea of making the book was prompted by the enshrining of Columba’s remains, which took place at some point in the middle years of the eighth century.

Viking raids

![Why was the decoration never finished? There are five pages at the beginning of St Matthew’s Gospel where the decoration was barely started. At this point the text is arranged in double columns: here we have the upper left quadrant, with a lion and a bird in combat. The frame has been prepared in outline, along with a few details of the ornament. Surprisingly, some paint was applied long before the drawing was complete. (The Book of Kells, folio 30v [detail], © The Board of Trinity College Dublin 2013](https://www.historyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/10-244x300.png)

Why was the decoration never finished? There are five pages at the beginning of St Matthew’s Gospel where the decoration was barely started. At this point the text is arranged in double columns: here we have the upper left quadrant, with a lion and a bird in combat. The frame has been prepared in outline, along with a few details of the ornament. Surprisingly, some paint was applied long before the drawing was complete. (The Book of Kells, folio 30v [detail], © The Board of Trinity College Dublin 2013

So how does all this help in understanding the circumstances in which the Book of Kells was made? In short, it is impossible to believe that an abbot of Iona could have commissioned a gospel-book of such complexity, containing such a range of colour and sheer joie de vivre, in times of appalling danger. Of course, it might be argued that the book was conceived as an act of atonement, a way of seeking divine aid in a time of distress, but, if so, the character of the decoration would surely have been very different and the book designed in a more rapid way.

The Viking raid of 802 was evidently one reason for the foundation of the monastery at Kells two years later, a site located well away from the coast and no doubt thought to be safe from raids from the sea. This has led to the suggestion that the gospel-book was subsequently completed there. But this argument makes no sense, because the book was never completed. Had it been taken to Kells early in the ninth century, the unfinished folios could surely have been finished. Especially interesting is the fact that the book was bound without some of its intended decoration. There are, moreover, curious omissions: a depiction of the Crucifixion seems to have been envisaged but never completed, and portraits of Mark and Luke are likewise missing. Were these ripped out of the book later in its history, or were they just not ready or available when it was time for the folios to be bound together? Given that the making of the Book of Kells must have been a prestige project of the highest order, it is tempting to assume that some unforeseen crisis intervened: the terror brought about by the Vikings surely represents one such crisis.

Exorcism

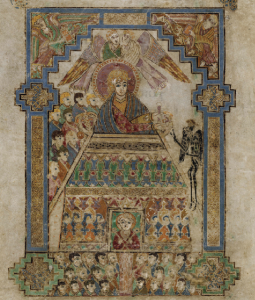

Some years ago Bernard Meehan pointed to a further mystery. This concerned the illustration of the Temptation of Christ, where minute examination of the black devil has revealed a series of stab-marks. This was not a random attack, because the marks are restricted to the figure of the devil alone. The attack on the devil—if that is what it was—apparently took place in antiquity, but there is no evidence to show exactly when. The desecration has the hallmarks of exorcism, a liturgical practice prominent in the early church. One of the powers associated with the saints was their ability to cast out demons, and there are a number of panels on the Irish high crosses that show the clergy overcoming evil spirits. The importance of exorcism is underlined by the existence of the exorcist, a specific office listed among the seven grades of clergy. Books, bells and croziers have been traditionally associated with the practice, and it would be no surprise to learn that the Columban community turned to their sacred books in the face of Viking horror, a time when it must have seemed that the devil incarnate was running amok. Perhaps this was when the black painted devil on folio 202v was stabbed; without firm evidence, of course, we will never know.

The ‘work of angels’?

Attacking the devil. In this full-page miniature, Christ, at the summit of the Temple, is being tempted by the devil. As Bernard Meehan has pointed out, the black, skeletal devil was at some unknown date mutilated by a series of small stab-marks—a reminder, perhaps, that books occasionally played a part in the practice of exorcism, accompanying pleas for divine intervention. (The Book of Kells, folio 202v, © The Board of Trinity College Dublin 2013)

The mutilated devil reminds us of the sacredness of the manuscript and the fact that the book itself evidently became part of the minna of Columba, venerated through its association with the saint. Is this a clue as to why it remained unfinished? Once the work was interrupted, the community may have lost the desire to continue, especially if some of the original scribes were now dead (or had perhaps been killed). The book was associated with more peaceful times, before the Columban communities were beset by Viking slaughter. It may have seemed wrong to tamper with what, even then, could have been regarded as a ‘work of angels’. Whatever happened, there must have been a conscious decision not to finish the illumination. When the book was eventually taken to Kells, possibly in 878, there were surely opportunities to complete the missing sections, opportunities that were apparently never taken.

The sequence of events outlined above remains, of course, hypothetical, but it is only by proposing hypotheses and testing them against the facts that we have any hope of getting closer to the truth. The most plausible reading of the evidence suggests that the gospel-book of Columba—the future ‘Book of Kells’—was started on Iona well before 793 and much of what we see today was evidently finished by that date. It was still incomplete in the 790s, and the disruption and fear caused by Viking activities may well have inhibited further work. In fact, the tribulations experienced by the community on Iona, not least the massacre of 806, may have helped to transform the gospel-book into a relic or sacred memorial of a bygone age. HI

Further reading

J. Marsden, The fury of the Northmen: saints, shrines and sea-raiders in the Viking age, AD 793–878 (London, 1993).

B. Meehan, The Book of Kells (London, 2012) [reviewed pp 56–7].