Dervorgilla: scarlet woman or scapegoat?

Published in Features, Issue 4 (Winter 2003), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 11

The pious old man clutches his pilgrim staff as he crests a hill overlooking Lough Gill. He turns to view his kingdom laid out before him. It is Tiernan O’Rourke (Ua Ruairc), prince of Breffni (Bréifne), on his way to make pilgrimage to the holy island of St Patrick at Lough Derg. His sweeping gaze takes in his castle at Dromahair. His keen eye detects a flutter of white linen on the battlements. His heart swells with love and pride. His beautiful and loving young wife, Dervorgilla, is signalling her devotion to him. With a sigh of contentment, he turns and drops slowly from sight.

The white linen still flutters. It is indeed a signal, but not of devotion to her aged husband! The small band of horsemen hidden in a nearby wood also observe the flutter of white atop the battlements. Their leader, a large imposing figure, is Diarmait McMurrough (MacMurchada), king of Leinster. He has travelled far from the south at the behest of the fair Dervorgilla. Many letters have passed between them to arrange this moment. The signal indicates that the coast is clear.

His heart pounding, McMurrough clatters into the cobbled courtyard of the castle. Swiftly he dismounts. Dervorgilla flies into the arms of her beloved. He remounts and sweeps her up onto the saddle beside him. The lovers turn south for McMurrough’s capital at Ferns, in the heart of his kingdom of Hy Kinsella (Uí Chennselaig). His small band of followers gather her furniture and cattle and follow.

Tiernan O’Rourke returned from pilgrimage to the valley, which lay smiling before him. As he came in sight of his castle he was seized with a sense of foreboding.

I looked for the lamp which she told me

Should shine when her pilgrim returned;

But tho’ darkness began to enfold me,

No lamp from the battlements burned.

Dervorgilla was gone! He quickly learned from his servants of the arrival of the small band of horsemen who took Dervorgilla, her cattle and her furniture and fled south. From the description of their leader he instantly recognised his arch-enemy, Diarmait McMurrough.

Consumed with rage, Tiernan O’Rourke swiftly sought out the high king, Turlough O’Connor (Ua Conchobhair), and explained the outrage. McMurrough had abducted his young wife and taken her to his capital, Ferns. Turlough O’Connor and Tiernan O’Rourke raised an army. They invaded Leinster and recovered Dervorgilla. McMurrough was banished. He fled to Bristol and returned with the Normans to recover his kingdom. More than seven centuries of foreign oppression had begun, and what of Dervorgilla?

Oh degenerate daughter of Erin

How fallen is thy fame,

And thro’ ages of bondage and slaughter

Thy country shall bleed for thy shame.

And so the fable goes, according to Thomas Moore in his poem ‘The valley lay smiling before me’. But what really happened in that fateful year of 1152? Did Dervorgilla elope with Diarmait McMurrough? Or was she abducted? Or was her departure to Ferns for some other reason?

Who was Dervorgilla?

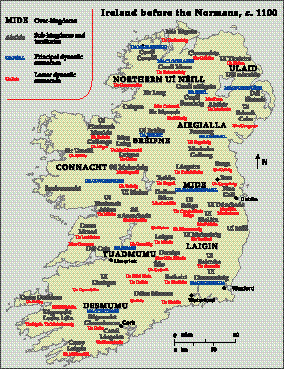

Dervorgilla was the daughter of Murchad Maelseaclainn (Ua Máelsechnaill), king of Meath (Mide), which was the fifth and richest province of Ireland, stretching from the sea at Drogheda to the Shannon and including the modern counties of Meath and Westmeath together with parts of Kildare, Offaly and Laois. The residences of the Maelseaclainns, which enjoyed relative immunity during the first part of the twelfth century, were Durrow and Clonard. Dervorgilla was born in 1108, most likely at Durrow, as this was the residence where her father died in 1153 and where her brother Maelseaclainn was poisoned in 1155.

Meath was surrounded by the four most formidable power-players of this and perhaps any other period in the history of the struggle for the high kingship, contested since the death of Brian Boru at Clontarf in 1014. To the west was Turlough O’Connor, king of Connacht and high king (with opposition) from 1122 to 1156. North-west lay the territory of Tiernan O’Rourke, prince of Breffni and Conmaicne—the modern counties of Leitrim, Longford and Cavan. Further north Muircheartach MacLoclainn reigned as king of Ulster and later high king (also with opposition) from 1156 to 1166. South-east sprawled the kingdom of Leinster under the watchful eye of its astute leader, Diarmait McMurrough, who ruled from the heartland of Hy Kinsella, whose capital was at Ferns.

The struggle for the high kingship

Meath was the key to the high kingship, with its ancient connection to Tara and the political power afforded by the division of its rich land, which was bartered to shore up ever-shifting alliances. The province was invaded seventeen times between 1125 and 1175.

It was indeed a period of swiftly shifting alliances, and in a vain effort to protect his kingdom Murchad Maelseaclainn gave his daughter Tailtu in marriage to Turlough O’Connor in the west and her younger sister Dervorgilla—described by Maurice O’Regan, secretary to Diarmait McMurrough, as ‘a fair and lovely lady’—to Tiernan O’Rourke. It was 1128 and she was twenty years old.

Up to 1150 Turlough O’Connor ruled with an iron hand. His strategy was ‘divide and conquer’. To this end he set about weakening the subkingdoms nearest to his power base in Connacht. He protected his southern borders through invasions of Munster, dividing that kingdom between the O’Briens (Ua Briain) and the McCarthys (MacCarthaig), thus ensuring that no single strong ruler emerged. He employed the same policy in Meath.

Then on to the stage crashed the mighty warlord MacLoclainn, his eyes firmly fixed on the high kingship. In 1150 O’Connor had to submit to him and give him hostages. The stage was being set for the dramatic events of 1152.

In 1152 Turlough O’Connor made peace with MacLoclainn and together, with McMurrough acting as advisor, they once again divided Meath. Murchad Maelseaclainn, Dervorgilla’s father, was given the western half and his son Maelseaclainn Maelseaclainn got the eastern portion. The forces of MacLoclainn, O’Connor, McMurrough and the men of Meath swept across the borders of Breffni and Conmaicne, deposing Tiernan O’Rourke and driving him back into northern Leitrim. They replaced him with a new ally, Aed O’Rourke.

The ‘abduction’

It is now that the fabled elopement or abduction of Dervorgilla, wife of Tiernan O’Rourke, is alleged to have taken place. The Annals of the Four Masters describe the event as follows:

On this occasion, Dervorgilla, daughter of Murchad Maelseaclainn and wife of Tiernan O’Rourke, was brought away by the king Leinster [Diarmait McMurrough], with her cattle and her furniture, and he took her according to the advice of her brother Maelseaclainn.

The Nuns’ Church, Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly, completed by Dervorgilla in 1167. (Díºchas)

No mention of elopement or abduction!

Before the invasion of O’Rourke’s territory, Maelseaclainn Maelseaclainn requested McMurrough to remove his sister Dervorgilla and her property out of the path of the invading armies, to ensure her safety. McMurrough complied and took her to the protection of his capital at Ferns. Now the struggle for the high kingship intensified, watched carefully from a distance by McMurrough. Turlough O’Connor and his son Rory invaded Meath but were driven out by MacLoclainn, who then restored Tiernan O’Rourke to Breffni. O’Rourke submitted to MacLoclainn, who granted all of Meath to Dervorgilla’s brother, Maelseaclainn, who also submitted to MacLoclainn.

He had now hemmed in O’Connor on two sides with two power blocks, each led by a single strong leader. This was the very scenario that O’Connor had tried to prevent through his divide-and-conquer strategy. All that now remained was the unification of Munster under MacLoclainn and the blockade would be complete. MacLoclainn marched on Munster and restored O’Brien, who in turn submitted to MacLoclainn. The isolation of O’Connor was accomplished—or was it?

All this time McMurrough was watching and awaiting developments. He knew that he had the key to the outcome in his possession—Dervorgilla! It was now that her ‘safe conduct’ status changed to ‘political hostage’. McMurrough had watched the machinations of Turlough O’Connor for more than twenty years. He believed that the incumbent high king would overcome the new contender, MacLoclainn. He was prepared to assist in deciding the outcome.

We can only speculate as to what happened next. There must have been communication between McMurrough and O’Connor at this point. Now the Annals take up the story:

An army was led by Turlough O’Connor to meet McMurrough, king of Leinster, to Doire Gabhlain, and he took away the daughter of Maelseaclainn and her cattle from him, so that she was in the protection of the men of Meath. On this occasion Tiernan O’Rourke came into his house and gave him hostages.

The army that O’Connor led into Leinster was not an invading army. There is no record of plunder or pillage. Perhaps it was not an army at all but simply the high king’s retinue. He was allowed to progress to the borders of Hy Kinsella, which were protected by the Blackstairs Mountains. At a place called Old Gowlin, on the western slopes of these mountains, McMurrough met him along with Dervorgilla and her property. He handed her over to O’Connor, who took her back to the protection of the men of Meath. The kingdom of Meath was now on side. Immediately Tiernan O’Rourke, in a remarkable volte-face, deserted MacLoclainn and submitted to O’Connor. The blockade was broken! It was 1153, a year since Dervorgilla was taken to Ferns.

MacLoclainn retaliated by invading Connacht and Breffni. Two years later (1155) Dervorgilla’s brother, Maelseaclainn Maelseaclainn, was poisoned at Durrow. And a year after that (1156) Turlough O’Connor died and was buried at Clonmacnoise. MacLoclainn assumed the high kingship (with opposition) for the next ten years (1156–66). He confirmed McMurrough as king of Leinster.

The consecration of Mellifont

In 1157 there was a great gathering of nobles and clergy at Mellifont for the consecration of the first Cistercian monastery in Ireland. The land and the building materials had been donated by Donnachad O’Carroll, king of Airgialla (Louth, Monaghan and part of Fermanagh), at the request of St Malachy in 1142. St Malachy had visited St Bernard at Clairvaux in 1140 and had been very impressed by the Cistercian rule and discipline. He asked St Bernard to train some of the young men of his retinue in the Cistercian way and return them to Ireland together with a team of French Cistercian architects with the objective of building the first Cistercian house on a site that he would provide. After a number of false starts and much dissension between the Irish and French brethren, culminating at one stage in the withdrawal of the entire French contingent back to Clairvaux, Mellifont was at last ready for consecration.

Gathered to celebrate the great day were MacLoclainn, the high king, Donnachad O’Carroll, king of Airgialla, Tiernan O’Rourke of Breffni, the archbishop of Armagh and primate of all Ireland, and seventeen other bishops. According to the Annals of the Four Masters, ‘the number of persons of every other degree was countless’. Present as an equal amongst equals was Dervorgilla, wife of Tiernan O’Rourke. She presented 60 ounces of gold, a gold chalice for the altar of Mary and nine cloths for the other altars of the church. Her gift was exceeded only by that of the high king himself, who also donated 60 ounces of gold and a townland to Drogheda. Conspicuous by his absence was Diarmait McMurrough, who as king of Leinster should have been there, particularly in view of the fact that St Bernard himself had written to him in 1151 and made him a member of the Cistercian confraternity. Perhaps his conscience was bothering him.

The coming of the Normans

MacLoclainn’s reign came to an abrupt end in 1166 when he was killed by Donnachad O’Carroll and Tiernan O’Rourke. Rory O’Connor now assumed the high kingship (still with opposition). He then joined forces with O’Rourke and marched on Ferns, destroying the castle and capturing McMurrough, who expected to be killed or at least blinded. He could not believe his luck when O’Connor simply banished him. He fled to Bristol on 1 August 1166 and from there made his way to Aquitaine and an audience with Henry II, king of England. McMurrough offered fealty in return for permission to recruit amongst Henry’s barons in Wales. He returned to Ireland in 1167 with Richard Fitz Godebert and a small band of Flemings, who helped him recover his kingdom, Hy Kinsella.

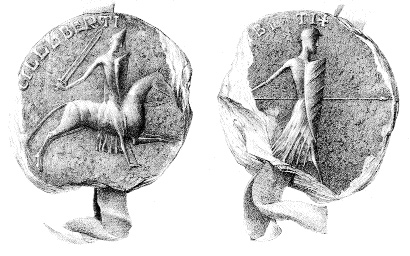

Strongbow’s seal. (British Library)

Rory O’Connor and Tiernan O’Rourke once again marched against him, forcing him to submit and to give seven hostages. McMurrough was forced to pay O’Rourke 100 ounces of gold as compensation for the holding of Dervorgilla fifteen years previously. In 1169 more Normans arrived in Wexford to aid McMurrough. He was again attacked by O’Connor and O’Rourke and forced to submit.

On 23 August 1170 the main Norman force under Richard de Clare, earl of Pembroke (a.k.a. Strongbow), landed near Waterford. Two days later Strongbow cemented his alliance with McMurrough by marrying his daughter Aoife. Within the month McMurrough and his Norman allies had taken Dublin. But before McMurrough could make his own bid for the high kingship old age caught up with him; he died on 1 May 1171 and was buried at Ferns. In the meantime, Rory O’Connor had laid siege to Strongbow in Dublin. Although heavily outnumbered, Strongbow and his knights staged a daring sortie that lifted the siege, but before he could consolidate his position Henry II, backed by papal authority, landed in Ireland and demanded his submission. Twelve years later, in 1183, Rory O’Connor, king of Connacht and last high king of Ireland, also submitted and retired to the Augustinian monastery at Cong. The Norman conquest was complete… for now!

Conclusion

So where did the stories of elopement and abduction come from, and why have they persisted to this day? There are three sources, each with a particular objective and each supported by a powerful propaganda medium. The abduction version came from Tiernan O’Rourke, while the elopement story was disseminated by Diarmait McMurrough and the Normans. O’Rourke could not contemplate his wife eloping with his most hated enemy. He supported abduction to deflect opinion away from this possibility, to raise feelings against McMurrough, and to bring the might of the Brehon Laws to bear against him. He could be pursued on two fronts. The righting of an ‘injustice’ was one of three justifications for overthrowing a king. The other avenue of pursuit was payment of an ‘honour price’ for injury to another or violation of protection. Dervorgilla was clearly under McMurrough’s protection, having been placed there by her brother for her safety. By changing her status to ‘hostage’ he violated that protection. None of the Annals speak of abduction except those of Clonmacnoise, which state in the most strident terms that he took her ‘to satisfy his insatiable carnal and adulterous lust’. The O’Rourkes had a long association with Clonmacnoise. It was also in Turlough O’Connor’s interest to be cast in the role of ‘just king’, righting a breach of the law, rather than as a party to using a defenceless woman to further his own interest. Clonmacnoise has been described at this time as being a fifth column for Connacht and therefore under O’Connor’s influence.

Diarmait McMurrough had a deep and long-standing hatred of Tiernan O’Rourke, dating back to the time when, as a young and inexperienced king of Leinster, O’Rourke had humbled him in battle. Probably to enrage O’Rourke he proclaimed that Dervorgilla loved him and that she herself arranged the ‘elopement’. His chronicler, Maurice O’Regan, an ardent defender of his master through the Song of Dermot and the earl, states:

That she would let King Dermot know

In what place he should take her

Where she should be in concealment

That he might freely carry her off.

Muiredach’s High Cross, Monasterboice, Co. Louth, a few miles beyond Mellifont. It is likely that Dervorgilla stood before it and perhaps pondered all that had happened since her youth, which she spent in the shadows of another high cross in faraway Durrow. (Shournagh Designs)

Interestingly, the Song of Dermot and the earl then goes on to say:

While he did not love her at all

To avenge, if he could, the great shame

Which the men of Leath Cuainn wrought of old

On the men of Leath Mogha in his territory.

Clearly, McMurrough had his own agenda after the fifteen-day period of protection, which was the maximum under law that he could offer, turned into revenge against O’Rourke and the manipulation of a valuable hostage.

The Norman historian, Giraldus Cambrensis, an ardent anti-feminist, in his Expugnatio Hibernica further muddies the waters:

No doubt she was abducted because she wanted to be and since woman is always a fickle and inconstant creature, she herself arranged that she should be the kidnapper’s prize. Almost all the world’s most notable catastrophes have been caused by women, witness Mark Anthony and Troy.

He then goes on to say that Rory O’Connor, in retaliation, raised an army and drove McMurrough from his kingdom, blithely ignoring the fourteen years between the taking of Dervorgilla (1152) and McMurrough’s expulsion (1166). He also glosses over the fact that two high kings ignored the supposed crime. Turlough O’Connor did nothing to McMurrough up to the time of his death, four years after the event. MacLoclainn ignored it for the entire ten years of his reign. Even Rory O’Connor made no mention of abduction when he banished McMurrough. It wasn’t until the following year, when he returned with his band of Flemings and was defeated again by Rory, that the question of an honour price for Dervorgilla arose, doubtless a humiliation instigated by O’Rourke.

If Dervorgilla had eloped, she would have been considered under the law as ‘an absconder from the law of marriage’; she would have forfeited all rights in society and could not have been harboured by anyone of whatever rank. Clearly she was not considered an outcast from society, as she stood at the consecration of Mellifont, an equal in the company of the highest in the land, both religious and secular. She was taken into McMurrough’s protection with the permission of her kin. He then abused that protection by holding her as a hostage.

This is not a unique conclusion. O’Clerigh, in his History of Ireland to Henry II, states: ‘A careful sifting of the evidence proves that there was no elopement and no romance. Dervorgilla, in our judgement, was taken away for safety and as a hostage with the consent of her family.’ A.M. Sullivan in his Story of Ireland claims that ‘Dervorgilla was badly treated by history’, and goes on to say that both the eminent historians O’Donovan and O’Curry were of the same view.

When Dervorgilla died at Mellifont on 25 January 1193, she was 85 years old and had outlived by many years all the participants in the drama of 1152.

Jim Toohey is a tour bus guide with an interest in medieval history.

Further reading:

G. Cambrensis, Expugnatio Hibernica (Dublin, 1998).

G.H. Orpen, The song of Dermot the earl (Oxford, 1892).

S. Duffy, Atlas of Irish history (Dublin, 1997).