Marriage in Medieval Ireland by Art Cosgrove

Published in

Anglo-Norman Ireland,

Features,

Gaelic Ireland,

Issue 3 (Autumn 1994),

Medieval History (pre-1500),

Medieval Social Perspectives,

Volume 2

The Marriage of the Princess Aoife of Leinster with Richard de Clare, Earl of Pembroke (detail) by Daniel MacLise.

( NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND)

Medieval Ireland was, according to contemporaries, a country divided into two ‘nations’. On the one hand there were the descendants of the Anglo-Norman settlers of the late twelfth and early thirteenth century, on the other the successors to the older Gaelic Irish population. The church reflected this division and was split into two sections, one inter Ang/icos (among the Anglo-Irish), the other inter Hibernicos (among the Gaelic Irish). We must therefore investigate marital behaviour in the two parts of Ireland, the section of the country under English law, and the Gaelic Irish area where the old brehon law still held sway.

Consent

Church law on marriage was defined and clarified during thetwelfth and early thirteenth centuries. Basic Christian teaching was straightforward – what God has united, man must not divide (Mark 10:10). But how do you know when God has united a man and a woman in matrimony, or, in other words, what constitutes a marriage? The matrimonial bond was created by the consent of the two parties, freely given, preferably expressed in a public ceremony. One of the consistent aims of the church was to have marriages publicly celebrated. But many marriages did not conform to this ideal. A public ceremony was not required to make a marriage valid and indissoluble. Because the consent of the couple rather than the church ceremony was the essential element, the church recognised unions which took place without its knowledge or blessing. The ‘private’ celebration of marriage had obvious disadvantages, particularly if the partners subsequently disagreed. A public ceremony safeguarded the contract. Yet because many people believed that they could regulate their marriages for themselves, clandestine unions remained common and, inevitably, produced more disputes than those which observed all the formalities laid down by the church. The church also defined those impediments which prevented individuals from validly contracting marriage. Obviously if one partner had married before and the spouse was still living, it was impossible to enter upon a second marriage. Those who had taken solemn religious vows or major holy orders were also prohibited from matrimony, and the parties to a marriage had to have reached the age of puberty (fourteen for boys, twelve for girls) before they could make a binding contract. The church also forbade marriage between those who were considered to be too closely related. The regulations on marriage were designed for universal application throughout the western church. And since it was the church that determined what constituted or did not constitute a marriage, it was accepted that marriage disputes should he heard only in church courts. How were the regulations observed in Ireland between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries? The evidence is not very satisfactory. The records of ecclesiastical courts do not survive for any Irish diocese, therefore we are forced to rely on the incomplete and haphazard records of marriage litigation which appear among the registers of the medieval archbishops of Armagh. From the late fourteenth to the early sixteenth century we are provided merely with glimpses of an Irish ecclesiastical court dealing with marriage disputes. This, in itself, means that the evidence is biased, but it is unfortunately true that marital harmony tends to leave little trace in the records.

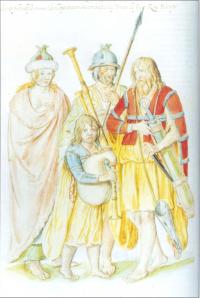

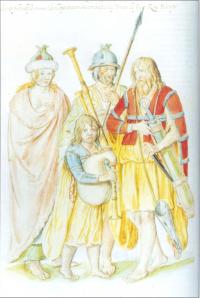

Irish people ‘as they went attired in the

reign of the late King Henry’, pre-1547,

Lucas de Heere, watercolour (CENTRAL

BIBLIOTHEEK, RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT, GHENT)

Concubines

Within Gaelic Ireland marriage behaviour had long been the target of criticism. Throughout the eleventh and twelfth centuries church reformers attacked a pattern of marital behaviour based not on the canon law of the church but on much older traditions. Thus Irish law on marriage permitted a man to keep a number of concubines, allowed divorce at will followed by the remarriage of either partner, and took no account of canonical prohibitions regarding consanguinity or affinity. It is not surprising to find, therefore, that one of the benefits which Pope Alexander III hoped might accrue from Henry II’s visit to Ireland in 1171-2 was a reformation In Irish marriage customs. But traditional marriage behaviour seems to have survived the coming of the Anglo-Normans, at least among . the higher ranks of Gaelic Irish society. Many men and women among the aristocracy continued to have a succession of spouses and this was a key factor In the proliferation of some of the major families. For example. Pilib Mag Uidhir, lord of Fermanagh (d. 1395), had twenty sons by eight mothers and Toirdhealbach 6 Domhnaill, lord of Tir Conaill had eighteen sons by ten different women. This marriage pattern may have been confined to the upper reaches of Gaelic Irish society; lack of evidence prevents any estimate of marital behaviour lower down the social scale. For the Gaelic Irish aristocracy real difficulties were caused by canonical regulations on consanguinity and affinity. In a letter to the pope in July 1469 seeking a dispensation from impediments of consanguinity to permit Enri 6 Neill to marry Johanna MacMahon, archbishop Bole of Armagh made the general point that several of the leading men in Ireland ‘are living in incestuous relationships, because they can rarely find their equals in nobility, with whom they can fittingly contract marriage, outside the degrees of consanguinityand affinity’.

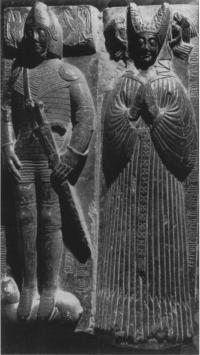

Townswomen: married and maid c.1547, Lucas de Heere, watercolour.

(CENTRAL BIBLJOTHEEK, RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT, GHENT)

Affinity and consanguinity

The impact of the church regulations on affinity and consanguinity was naturally much greater in smallscale societies like those in Gaelic Ireland, and the frequency with which dispensations were sought is an indication of their effect. But, equally, the desire to be dispensed, often at considerable trouble and expense, shows that there were many who were not prepared to flout the church law. What was it that prompted couples to seek these dispensations? In the Anglo-Irish area the desire to safeguard inheritance rights could well have been a factor, but this was less important for the Gaelic Irish aristocracy, among whom acknowledgement of paternity rather than canonical concepts of legitimacy determined hereditary entitlements. Perhaps a troubled conscience, a wish to conform to church regulations, may explain some of them. Certainly there can hardly be any other reason for the dispensation sought in 1448 by Aedh 6 Conchobair, described as a nobleman of the diocese of Kildare. Prior to his marriage to Honora Nic Ghiolla Phadraig he had sexual relations with both her sister and another woman related to her in the third degree of affinity, thus invalidating the union. But these affairs were unknown to Honora’s friends and to all others, and the bishop of Kildare was therefore authorised to absolve Aedh, dispense from the impediments created by his pre-marital behaviour and permit the couple to contract marriage again.

Cases initiated by women

A number of cases were initiated by Gaelic Irish women who sought to have their husbands restored to them, sometimes after years of separation. In 1397, Una O’Connor sought redress. She had been dismissed by her husband, Manus 6 Catha-in, without any court judgement and replaced by a concubine. Katherine O’Doherty complained that her husband,

Manus McGilligan, ignored the decision of the Derry diocesan court that she was his legitimate wife and openly consorted with other women. The attitude of Gaelic Irish men of rank towards the canon law and the ecclesiastical courts is best illustrated, perhaps, by the case involving Muircheartach Ruadh 6 Neill, head of the O’Neilis of Clandeboye (1444-68). O’Neill had married Margaret, daughter of Maghnus Mac Mathghamhna and had subsequently deserted her for a woman named Rose White. In justification he claimed that his marriage to Margaret was invalid by a tie of affinity since he had previously had sexual relations with Margaret’s first cousin Maeve. In support of his contention, he brought forward the explicit evidence of one Aine ‘new Owhityli’, a fifty year-old woman. In her deposition she stated that Muircheartach had been captured and detained by Maeve’s father, Ruaidhri Mac Mathghamhna; during the period of captivity he often had Maeve with him in bed. The witness claimed that she herself had shared the same bed, that she had often seen the couple naked together and that she was certain that sexual intercourse had taken place between them. She admitted that Maeve had not become pregnant, that she was uncertain about the date of the alleged incidents but that they had taken place within Ruaidhri’s dwelling without his knowledge. But the court refused to accept this evidence, clearly taking the view that the story had been fabricated to provide a pretext whereby Muircheartach could escape from an unwelcome marriage. And although the case dragged on for over two years, the eventual decision of the archbishop of Armagh in December 1451 was that the marriage between Muircheartach and Margaret was valid; O’Neill was ordered, under pain of excommunication, to separate from Rose White and to accept Margaret as his legitimate wife. Muircheartach was acting in a manner sanctioned by Gaelic Irish tradition. Yet clearly he felt that the canonical regulations could not be ignored; otherwise he would hardly have gone to the trouble of mounting his ultimately unsuccessful defence. Nevertheless, the clash between two quite different concepts of marriage and its function in society continued throughout the middle ages. The problem was that women regarded as concubines by the church often enjoyed the same legal and social status as wives in Gaelic society, and the children of such women were accorded the same rights as those of the canonically recognised wife.

Marriage in Anglo-Ireland

Within Anglo-Ireland the secular legal system presented no such challenge to the canon law. Church influence was clearly greater. For instance in the late fifteenth century when it became known that Patrick Goldsmith was living adulterously with Belle Barry in Dublin, the mayor expelled Belle from the city for a year. The measure had only a limited effect since Patrick would secretly bring Belle from Kilmainham to his room at night, but it is indicative of a desire on the part of the municipal authorities to support church rulings. The Dublin administration did attempt to regulate marriage practices in one way. Concern about the threats to the security and cultural identity of the colonial settlement posed by intermarriage with those hostile to it led to restrictions on the choice of marriage partner. The ordinance of 1351 forbade marriage between the colonists and any enemies of the king, whether Gaelic or Anglo-Irish. Fifteen years later the Statutes of Kilkenny imposed a ban based solely on ethnic grounds, prohibiting any ‘alliance by marriage … concubinage, or by caif (coibche) , between the Anglo-Irish and the Gaelic Irish.

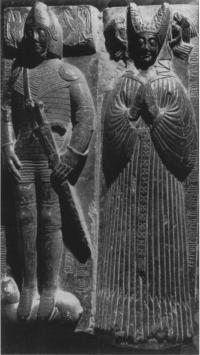

Effigy of Margaret Fitzgerald and her husband Piers Butler, eighth Earl of Ormond in St Canice’s Cathedral

Kilkenny.

Secular courts

Though lacking the competence to adjudicate on the validity of marriage, the secular courts did have to deal with offences that arose out of marital strife. The most notable case of this type was heard at Cork in May 1307. It concerned John Don, a wine merchant from Youghal, who married a woman called Basilia and shortly afterwards went abroad on business. During his absence Stephen O’Regan came to John’s house ‘asking Basilia that he might be her friend. She lightly consenting, they lay together .. Jor the whole time that John was abroad’. On his return John was informed by his neighbours about what had been going on and, naturally irate, he forbade Stephen to visit his house in future.

Subsequently, however, when John was absent on a business trip to Cork, Stephen again came to the house and slept with Basilia. When John learnt of this second offence, he devised a plan to trap Stephen. He had, attached to his house, a tavern and the keeper of this promised him that he would let him know if Stephen came to visit Basilia again. On a day following John pretended that he was going to Cork on business but instead went to another house in Youghal. That evening, Stephen and Basilia dined together with one Stephen Ie Jeofne, who, unknown to the couple, seems to have been an ally of John. After supper Stephen O’Regan went to the tavern and drank some wine with the tavern-keeper. While they were drinking Basilia passed through the tavern to her bedroom. Stephen and the tavern-keeper followed her. Aware now of the need for discretion, Stephen and Basilia attempted to buy the silence of the tavern-keeper and Basilia’s maid by offering the former the sum of five shillings and the latter a cow. Then Stephen proceeded to take off his shoes, clearly intending to spend the night with Basilia. The tavern-keeper, faithful to his prior agreement with his employer, now went to the house of Stephen Ie Jeofne where John Don was waiting with a group of armed men. Once informed of what had happened, they proceeded to John’s house, hoping to catch the guilty couple together. The noise of the armed men’s approach alarmed Stephen and Basilia and they extinguished their candles. Stephen then decided to attempt an escape, but in the hall of the house he ran into John Don’s armed men. They threw him to the ground, bound his hands and feet, and then castrated him. Stephen succeeded in his action for assault and was awarded substantial damages of £20 against John Don and his associates. The latter avoided imprisonment by the payment of a fine of five marks (£3. 6s. 8d. ). A week later John Don counterclaimed against Stephen for compensation for goods destroyed or stolen from his house and was awarded £2 by the court.

Annulments

Almost all of the other evidence for marital behaviour in AngloIreland comes from the Armagh registers and is mainly concerned with the southern half of the Armagh diocese which was inter Anglicos, mostly contained in the modern County Louth. Suits to enforce marriage contracts formed one part of the court’s business; it also had to deal with pleas for annulment, a declaration that a marriage contract had been invalid from the outset. Annulments were sought on a variety of grounds. As already noted, a plea that the parties were related within the forbidden degrees of consanguinity or affinity might be made. More often the case was based on an allegation of pre-contract, that one party to a marriage contract was already validly married and thus disqualified from making a second marriage.In cases where pre-contract was alleged, the court had to establish not only the validity of the contract but also its date so as to ensure that it was made prior to the second marriage agreement. It then had to determine whether the spouse of the first union was still alive at the time of the second contract. On occasion this might involve the court in consideration of events that happened many years before. A case in 1481 turned on evidence of what had occurred thirty years previously. Thaddeus Carpenter sought the annulment of his union with Juliana Maynaghe on the grounds of a valid pre-contract between Juliana and Roger Sarsfield. A number of witnesses claimed that they had been present either at the church marriage ceremony or at the wedding-feast of Roger and Juliana in Ardee thirty years before. The couple had lived together for some time, but Roger then left and went to live in England. He was unable to persuade his wife to join him there and she then contracted marriage with Thaddeus Carpenter ‘before the Earl of Worcester came to Ireland’, that is, prior to 1467. Roger’s sister, Jeneta Sarsfield, testified that she knew that her brother was alive five years before because she had received a letter from him asking her to come to England. For good measure she added that only three years ago she had received a message from him via Milo Fleming, a merchant from Slane, requesting her to send her son to him in England.

Impotence

It is worth noting that the court always upheld the earlier valid contract. This it did even if the first marriage was made clandestinely and the second in church. While consent rather than consummation made a marriage valid, it was possible, nevertheless, to secure the dissolution of the bond on the grounds of impotence. Usually the woman pleaded her desire to be a mother and the inability of her husband to fulfil that desire, and the Armagh court did award annulments on those grounds. But the court was clearly aware of the danger of fraud or collusion and would not accept a plea of impotence without some form of substantiation, a precaution clearly justified in a case brought by Anisia Gowin in February 1521. In the previous December Anisia had failed in her bid to have her marriage to Nicholas Conyll nullified on the basis of pre-contract. She now charged her husband with impotence, a charge he denied. The court ordered that she was ‘to spend the night with Nicholas in the same bed, without any disturbance’ and appointed nine men to carry out an inspection of Nicholas and report their findings. Their evidence left no doubt as to Nicholas’s ability to perform his marital duties! Even when the man admitted impotence the court demanded corroboration from seven witnesses.

Conclusion

Overall the surviving records of matrimonial litigation among the Armagh registers support the view that marriage practices in AngloIreland did not differ markedly from those elsewhere in Latin Christendom. In Gaelic Ireland practices did diverge significantly but the corollary was a heavy demand for the sanction of canon law. In general, despite the best efforts of the church authorities, marriage was still widely regarded as a personal matter subject to a private contract between the parties. Clandestine unions remained common; and even after the Council of Trent’s decree outlawing such unions in 1563, clandestine marriage was to have a long history in Ireland.

Art Cosgrove is President of University College Dublin.

Further reading:

C.N.L. Brooke, The medieval idea of

marriage (Oxford 1989).

R.H. Helmholtz, Marriage legislation

in medieval England (Cambridge

1974).

J.A. Brundage, Law, sex and Christian

society in medieval society (Chicago

1987).

K. Simms, ‘The legal position of Irish

women in the later middle ages’, in

Irish Jurist New Series X (1975).

This article is an edited version of

‘Marriage in medieval Ireland’, in Art

Cosgrove (ed.), Marriage in Ireland

(Dublin 1985).