A map of Ballyfin demesne 200 years ago

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2015), Volume 23A little-noticed map made 200 years ago provides the first detailed representation of the parkland around one of Ireland’s most elaborate ‘big houses’, the recently restored mansion at Ballyfin, Co. Laois.

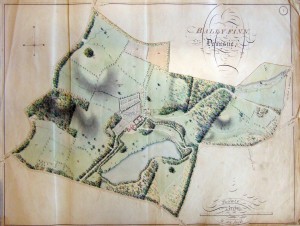

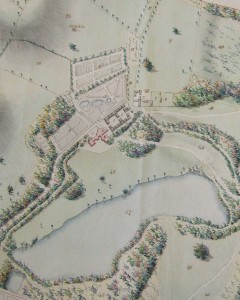

The map of Ballyfin demesne c. 1814 in the Delany Archive, Carlow College. Reference numbers shown in the detail (right): 1, Mansion house Flower Garden & Offices; 2, Farm Yard & Offices; 3, Kitchen Garden; 4, Middle Garden; 5, Melon Garden; 6, The Nursery; 7,8, Racer’s park; 9, The Paddock; 10,11, Crab Lane and Plantation; 12, Crab Lane Avenue; 25, Lime kiln field; 26, Four Acre field; 43, Fox Cover Plantation; 45, Wood adjoining the Lawn & Lake; 46, Rice’s field; 48, Horse park; 49, Old Turnip field plantation; 57, The Lake. Note the ice house located just south of field 49. (Brigidine Sisters)

To be found in a volume of richly coloured estate maps now preserved in the Delany Archive in Carlow College, a map (below) depicting Ballyfin demesne, Co. Laois, c. 1814 helps to amplify the story of one of Ireland’s greatest houses and demesnes. Occupied from the 1660s by the Pole family, the house and lands at Ballyfin were the focus during the middle decades of the eighteenth century of a massive—but apparently little-documented—exercise in landscape gardening that included a 12ha man-made lake and the enhancement of a rolling landscape of natural parkland. Much admired, the house and grounds, in the later stages of which the English landscape architect John Webb (c. 1754–1828) may have had a hand, were ‘unrivalled in improvements’. The house and setting created by the Poles, primarily William Pole (d. 1781), are featured by Thomas Milton in a view published in 1787 as part of a series depicting the seats of nobility and gentry in Ireland (p. 24). In 1813, however, with the Pole family fortunes by then interlinked with those of the Wellesleys and increasingly bound into English politics, William Wellesley-Pole (1763– 1845) sold Ballyfin to the young Sir Charles Henry Coote (1792–1864), who already had extensive landholdings in the then Queen’s County.

Pre-dates 1830s Ordnance Survey

Coote, who reached the age of majority in 1813 and who married in 1814, lived at Ballyfin for over 50 years. It was he who commissioned the architect Richard Morrison and his son, William Vitruvius Morrison, to rebuild the house and to create the grandiose interior that is now such a feature of Ballyfin. But in contrast to the far-reaching and extravagant changes made to the house itself, the changes to its setting were much more modest. The 1814 map—which is of particular interest, as no detailed map of Ballyfin has hitherto been known that pre-dated the late 1830s Ordnance Survey—provides clear evidence that the natural landscape surrounding Ballyfin is primarily a product of the earlier Pole and Wellesley-Pole periods of occupation.

Coote, who reached the age of majority in 1813 and who married in 1814, lived at Ballyfin for over 50 years. It was he who commissioned the architect Richard Morrison and his son, William Vitruvius Morrison, to rebuild the house and to create the grandiose interior that is now such a feature of Ballyfin. But in contrast to the far-reaching and extravagant changes made to the house itself, the changes to its setting were much more modest. The 1814 map—which is of particular interest, as no detailed map of Ballyfin has hitherto been known that pre-dated the late 1830s Ordnance Survey—provides clear evidence that the natural landscape surrounding Ballyfin is primarily a product of the earlier Pole and Wellesley-Pole periods of occupation.

Compiled by the Dublin land surveyor Thomas Logan and his son, the volume of maps depicts the Queen’s County estates of Sir Charles Coote, covering some 22,450 Irish plantation acres (around 36,350 statute acres, or 14,700ha) in the baronies of Maryborough, Ossory and Tinnehinch. Sixty-nine maps, most of them relating to individual townlands on the flanks of the Slieve Bloom Mountains and also taking in a large part of the town of Mountrath, are included. Coloured and produced in the ‘French style’ that had been initiated in Ireland during the 1750s and 1760s by the cartographers John Rocque and Bernard Scalé, the maps are mostly drawn at a scale of twenty perches to an inch or 1:5,040 (40 perches to an inch, 1:10,080, in mountain areas) and offer a realistic interpretation of the landscape, depicting the man-made features of buildings, enclosures and plantations alongside the ridges and rises, rivers and bogs produced by nature. In its leather-bound, gold-lettered cover, the volume must have been a proud achievement for Thomas Logan (c. 1777–1820) and his son Michael, with whom he worked during 1812– 16. Indeed, it was possibly one of their most significant commissions. Thomas Logan also undertook work for Trinity College and for various other landlords across Ireland, but the Coote estate volume appears to be his most substantial surviving work. It is easy to imagine this elegant volume occupying a prominent place in the drawing-room or in the library at Ballyfin throughout the period of Coote ownership. Its subsequent history (from the sale of the house to the Patrician Brothers in the 1920s) is unclear. At some point, however, it came into the possession of the Brigidine Sisters at Mountrath, and was later transferred to the Delany Archive in Carlow College.

What information is included?

Each of the maps in the volume offers information of interest to historians; many provide the names of the leaseholders of land and some also identify the names of the actual occupiers of property (not necessarily the same as the leaseholders). In the small rural townland of Balloughmore (near Roscrea) the new (Catholic) chapel is indicated, a building of great character that is still used for worship today. At another townland, Rearymore, a holy well dedicated to St Finian is marked. In the case of Mountrath town, that part of the town west of the White Horse River is omitted; now Coote Street, this area was then establishing a new Catholic chapel and schools in an atmosphere punctuated by sectarian tension. But, this important omission apart, the rest is included, indicating that the early nineteenth-century town was much larger than at present, containing as many as 500 buildings and a population that may have reached 3,000 or more. This was a place that had formerly been the site of a great ironworks owned by the Cootes but which in the early nineteenth century was associated with Quaker enterprise (the names Pim, Bewley, Edmondson and other names linked to Quakers in Laois are prominent), with a large cotton factory, a brewery and distillery and corn mills. The Logan maps capture Mountrath at or near the zenith of its economic development. Likewise, the map of Ballyfin demesne, the first in the volume, provides a unique insight into a very different landscape, just five miles from Mountrath, capturing the demesne as it was at the very start of the period under Coote control.

William Pole (d. 1781), the driving force in the development of eighteenth-century Ballyfin House. (Wikipedia Commons)

The demesne map shows that Ballyfin was a very distinctive landscape unit in the early nineteenth century, picked out by the extent of its plantations, its lake and parkland, and the concentration of buildings at the big house with its nearby out-offices. As with many other Irish demesnes, its distinctiveness was reinforced by its high wall (marked on the map by a red line), which remains a feature of Ballyfin today. The wall had both exclusionary and inclusionary functions (allowing the demesne to be a deer-park, for example). At least five buildings can be identified at various places close to the wall, these presumably being the residences of demesne workers, some of whose names appear to be recorded (Hutchinson, Rice and perhaps Moore, although this may have been family-derived). The total area was 345 Irish acres and two perches (approximately 560 statute acres). A reference table accompanying the map divides the demesne into 57 distinctive sub-units and shows that, as well as being an attractive landscape designed to give pleasure, the demesne also possessed the components of a working farm. Reached by an avenue from the south-west, the ‘mansion house’ faced south-eastwards to look across the lawn and the lake toward a distant prospect of the Wicklow mountains. A barracks-scale complex of out-offices, organised about two adjoining courtyards, was set to the north-east, with gardens, including a 4.6-statute-acre kitchen garden, a nursery and a small ‘melon garden’, to the north-west (map detail, p. 23). East of the house, too, was an extensive area that, to judge from the identifier names used in the reference, was primarily devoted to horses: here were ‘racer’s park’, the paddock, horse park and associated plantations, in one of which an ice house was located. Far to the east, close to the demesne boundary, was the church—a building which is still in use today. Northward, there was also an extensive ‘farmyard & offices’, and at least two fields in tillage—the pea field and the upper turnip field. Other ‘farm’-oriented fields included ‘cow park’ and ‘calf park’. A limekiln, at a high point which since c. 1850 has been occupied by a striking tower, was also a prominent feature to the north of the house in 1814.

Well-embedded landscaping

Thomas Logan’s map offers little direct evidence of landscaping in progress. An overall impression is that we are probably looking at a demesne where the landscaping is well embedded in front of the house and where other parts of the demesne have clearly assigned functions. Unfortunately no earlier map appears to show the demesne in much detail, making it more difficult to assess the timing and rate of landscape change. It is possible, however, to compare the 1814 map to the late 1830s 1:10,560 (6in. to one mile) Ordnance Survey map, Queen’s County sheet 12, which portrays the Ballyfin area. This comparison suggests that the main features of the demesne changed little during the two decades after it had been acquired by Sir Charles Coote. Apart from the house itself, the main change appears to have been to extend and perhaps strengthen some of the plantations, especially those along the periphery. Perhaps the costly challenge of changing and embellishing the house meant that its owner was content to do little with its environs. Thomas Logan’s beautiful map thus confirms that the landscape appearing on the Ordnance Survey map of Ballyfin dates from the early nineteenth century at latest, and is perhaps more likely to be earlier—an outstanding example of the ‘natural’ in landscape gardening and a place which, as early as 1759, Emily, Duchess of Leinster, deemed much beyond anywhere else she had seen in Ireland. This is a map that deserves a place in the unfolding narrative of Ballyfin.

Arnold Horner formerly taught geography at University College Dublin.

Further reading

J.H. Andrews, ‘The French school of Dublin land surveyors’, Irish Geography 5 (1967), 275–92.

C. Coote, Statistical survey of the Queen’s County (Dublin, 1801).

K. Mulligan, Ballyfin: the restoration of an Irish house and demesne (Tralee, 2011).

T. Reeves-Smyth, ‘Demesnes’, in F.H.A. Aalen, K. Whelan and M. Stout (eds), Atlas of the Irish rural landscape (Cork, 2011), 278–85.