Making sense of Thomas Paine (1737–1809)

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, General, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2009), Volume 17

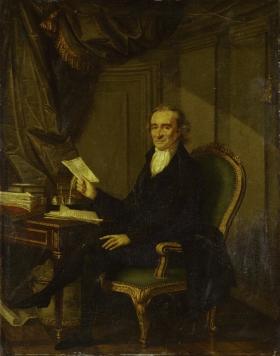

Thomas Paine by Larent Dabos, 1791. (National Portrait Gallery, London)

‘These are the times that try men’s souls’, George Washington declared to his troops as they gathered in darkness on the banks of the Delaware River before the crucial American victory at the Battle of Trenton (1776) in the Revolutionary War. Washington was quoting the opening lines from the first of Thomas Paine’s great pamphlet series The American Crisis, published just one week earlier. Paine wrote thirteen pamphlets in the series throughout the eight years of the war between the American colonies and the Kingdom of Great Britain, in which he documented the developments of the struggle, ridiculed the British and, to incalculable effect, entreated Americans to always be aware of what was at stake: ‘What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly. ’Tis dearness only that gives everything its value.’

The influence of Paine’s pamphlets on the successful outcome of the American struggle for independence cannot be overstated. ‘Washington’s sword would have been wielded in vain had it not been for the pen of Paine’, said James Monroe. But it is also true to say that there might not have been a War of Independence without Paine’s influence. Self-determination on issues such as taxation, not independence, was the goal of the Patriots. On 14 February 1776 the publication of Paine’s Common Sense changed the aspiration. In this, without question the most influential pamphlet of the American Revolution, Paine wrote about the design of government; he excoriated monarchy and hereditary succession; he condemned British rule and espoused American independence.

French Revolution

Paine was in London in July 1789 when the Bastille was stormed. He travelled to Paris in November of that year. In January 1790 he corresponded with Edmund Burke regarding the French Revolution, and the following month Burke gave a speech to parliament denouncing the Revolution. The following November Burke published his Reflections on the Revolution in France. Initially Burke was not opposed to the Revolution, writing in August 1789 about ‘England gazing with astonishment at a French struggle for Liberty and not knowing whether to blame or to applaud!’. But when a mob marched on Versailles that October to compel the king to return to Paris, Burke turned. He considered France a ‘country undone’, where ‘the elements which compose human society seem all to be dissolved, and a world of monsters to be produced in the place of it’. He considered that the revolution had ‘subverted monarchy, but not recover’d freedom’. Burke posited that social stability could only be achieved if an élite and wise group, whose wisdom is hereditary, governed.

In February 1791 Paine published Rights of Man: Being an answer to Mr Burke’s attack on the French Revolution, in which he described Burke’s Reflections as ‘darkness attempting to illuminate light’ and rebutted Burke’s assertions, stating that government was a contrivance of man and that hereditary rights to govern cannot compose a government because wisdom to govern cannot be inherited. The following year Paine published Rights of Man, Part the Second, Combining Principal and Practice, containing discussion on possible formats for a successful republic and proposals for programmes of education, pensions and other reliefs for the poor, and a system of taxation based on income to fund it. In October 1792 the Irish revolutionary Lord Edward Fitzgerald lodged with Paine, who voiced his support for a French-funded insurrection in Ireland. (More editions of Paine’s Rights of Man were published in Ireland than anywhere else in the English-speaking world.)

Arrested in Paris

In his inaugural speech in January 2009 President Barak Obama quoted Paine: ‘Let it be told to the future world that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet it’. (Getty Images)

In December 1793 Paine was arrested and imprisoned in the former Luxembourg Palace. Shortly before his arrest he began work on The Age of Reason; Being an Investigation of True and of Fabulous Theology, published in January 1794, in which he outlined his thoughts on religion. He wrote: ‘I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life. I believe in the equality of man, and I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavouring to make our fellow creatures happy.’ In this work, and in The Age of Reason, Part the Second (1795), Paine treated the Bible literally and applied reason and common sense to its content, debunking it with a cool logic. He argued that to be devout within the established religions one must make a sacrifice of the greatest gift from God, the gift of reason.

After James Monroe secured his release in November 1794, Paine remained in Paris until his return to America in 1802. During those years he wrote numerous pamphlets, including Dissertation on First Principals of Government (1795), in which he espoused universal male suffrage, abolished by the new French constitution; The Decline and Fall of the English System of Finance (1796), which predicted that war with France would cause the Bank of England to collapse; and Agrarian Justice (1797), in which he argued that all land was in the common ownership of humankind but that to better cultivate it property ownership was necessary. He proposed that those privileged enough to own land owed a debt to those who did not and suggested a property tax to assist the un-propertied poor. That same year Paine met Theobald Wolfe Tone and James Napper Tandy and encouraged their plans to surprise the English by landing a French army in Ireland.

Criticisms of Washington

In July 1796 Paine wrote an open letter to President Washington, accusing him of treachery and criticising his performance in the Revolutionary War. On his return to America Paine continued to attack Washington and John Adams. He received a letter from Samuel Adams, who described Age of Reason as a ‘defence of infidelity’, echoing the opinion of many. His attacks on Washington no doubt had a cooling effect on the affections many Americans had held for him. In the years following 1802 Paine contributed articles to various publications. In his final years he moved from lodging to poorer lodging. He died on 8 June 1809, his funeral attended by only a handful of people.

Paine’s works continued to influence thinkers and writers in his time and beyond. His influence is clear in the original Declaration of the United Irishmen, which alludes to the rights of man, common sense and common interests, and government originating from the people. Some suggest that Paine penned some or all of the American Declaration of Independence, and in the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights Paine’s philosophies loom large.

Speaking in 1805, John Adams stated: ‘I know not whether any man in the world has had more influence on its inhabitants or affairs for the last thirty years than Tom Paine’. Today it can be argued that no man has had more influence on the development of mankind’s understanding of individual rights, governance or freedom of expression for the last 200 years than Tom Paine. HI

Peadar Browne is a legal executive in a criminal law firm.

Further reading:

C. Hitchens, Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man: a biography (London, 2006).

H. J. Kaye, Thomas Paine and the promise of America (New York, 2005).

J. Keane, Tom Paine: a political life (London, 1996).