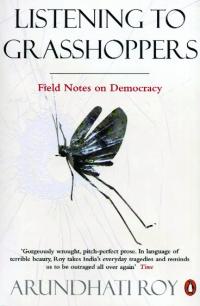

Listening to grasshoppers: field notes on democracy

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Book Reviews, Issue 4 (July/August 2010), Reviews, Volume 18 These essays initially appeared as ‘urgent public interventions at critical moments’ between 2001 and 2008. Collected together at the conclusion of India’s blockbuster 2009 general election, they present ‘a detailed underview’ of the consequences and corollaries of democracy (p. xi) and of partition’s long shadow. Gandhi once described independence as a ‘wooden loaf’ (p. 18)—notional freedom that left democracy hungry. Both Hindu and Islamic extremism is growing. The twenty-year conflict in Kashmir has claimed over 70,000 lives, and India and Pakistan have come to the brink of nuclear confrontation. Moves to ‘prevent terrorism’ have further served to bend and twist democracy ‘. . . into something unrecognisable’ (p. 14).

These essays initially appeared as ‘urgent public interventions at critical moments’ between 2001 and 2008. Collected together at the conclusion of India’s blockbuster 2009 general election, they present ‘a detailed underview’ of the consequences and corollaries of democracy (p. xi) and of partition’s long shadow. Gandhi once described independence as a ‘wooden loaf’ (p. 18)—notional freedom that left democracy hungry. Both Hindu and Islamic extremism is growing. The twenty-year conflict in Kashmir has claimed over 70,000 lives, and India and Pakistan have come to the brink of nuclear confrontation. Moves to ‘prevent terrorism’ have further served to bend and twist democracy ‘. . . into something unrecognisable’ (p. 14).

‘Listening to grasshoppers—genocide, denial and celebration’ commemorates Hrant Dink, the Turkish-Armenian newspaper editor assassinated in 2007 for highlighting the Ottoman genocide of the Armenians, a catastrophe foretold by swarms of grasshoppers—a bad omen. Roy argues that India needs Dink’s courage to say the unsayable, think the unthinkable and look for the lessons of the past. While the million and a half deaths in Turkey have been kept silent for generations, the killings of Muslims across Gujarat in 2002 were openly celebrated and manipulated for electoral gain. The Muslims were killed to avenge the deaths of 58 Hindu pilgrims burned alive on a train by ‘Muslim terrorists’ as they returned from a pilgrimage to Ayodhya, where a decade earlier the rising forces of Hindu extremism had destroyed the Babri Mosque and erected a Ram Temple in its place.

Contemporary Hindu neo-fascism echoes the Ottoman project of Union and Progress with its twin goals of Nationalism and Development. Today, ‘progress’ and ‘development’ are mapped onto economic reforms, deregulation and privatisation, and ‘freedom’ has come to mean consumer choice. Roy is alarmed by ‘this theft of language, this technique of usurping words and deploying them like weapons, of using them to mask intent and to mean exactly the opposite of what they traditionally meant’ (p. xiv). People are deprived of a language for resistance, as dissenters are dismissed as ‘anti-progress’ and ‘anti-national’ (p. xiv). ‘Development’ projects are carried out in the name of the poor but in reality displace them on a massive scale. Land and resources are at the centre of the struggle over progress; dams alone are responsible for displacing some 30 million people.

Three progressive parliamentary acts have recently conferred some basic protections against the depredations of a development model hungry for land, energy, minerals and water. Forest-dwellers have gained legal rights to land and resources. The Right to Information Act makes it possible to call both the government and the private sector to account, and the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act entitles impoverished families to 100 days’ work a year at the minimum wage—a last defence against destitution and starvation. Yet forest rights will be meaningless if no forests are left, and the Right to Information will be useless if it does not lead to redress. ‘Scandal in the Palace’ discusses the issues of corruption and élite complicity through the revelations about the former chief justice of India, Y.K. Sabarhwal, questioning the beneficiaries of his ruling that enabled the poor to be displaced so that areas of Delhi could be ‘redeveloped’.

The problem of Kashmir and the legacy of two Afghan wars somehow remain at the centre of the Hindu–Muslim and India–Pakistan antinomies that underpin these essays. During the 2008 Kashmir uprising, Roy spots a banner emblazoned with the plea: ‘Democracy without Justice = Demon Crazy’ (p. xi). She seems sympathetic to Kashmiri demands for freedom, azadi, seeing them as ‘a spontaneous and popular uprising of a caged enraged people’ (p. 169). Three of the essays concern Mohammad Afzal, sentenced to hang for his implication in a foiled attack on the Indian parliament on 13 December 2001. In Roy’s view, Afzal was ‘only a pawn in a very sinister game’ (p. 51) of India versus Pakistan, rendered infinitely more ominous by nuclear nationalism. All five attackers were killed, identified only by first names and the statement that they ‘looked like Pakistanis’ (p. 49). Afzal was one of three Kashmiri men implicated for conspiracy in the crime and sentenced to death. Only Afzal’s conviction remained following appeals, and he was sentenced to hang in 2006, though execution was deferred and he is still on death row.

Roy’s critics complain that her non-fiction writing lacks factual precision, but what is at stake is much larger—truth and the conditions of possibility for resisting the ‘theft of words’ and imagining different futures. Her tone is polemical, even hyperbolic, but then so is this subject-matter, recalling Rosa Luxemburg’s devastating Junius Pamphlet of 1915. In Roy’s view, we need not facts but ‘. . . a feral howl—the transformative power and real precision of poetry’ (p. xii). Two of the contributions are pieces of absurd theatre; one protests against George Bush’s visit to India in 2006, while the closing essay was part of a contemporary art project on imagined futures. These fictional works of allegory and parody are feral howls, reminding us that reality bites at the heels of power. HI

Su-ming Khoo lectures in sociology at NUI, Galway.

'