Lionel de Rothschild and the Great Irish Famine

Published in Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2022), Volume 30The origins of the British Relief Association

By Norbert Götz

The obituary of Lionel de Rothschild (1808–1879) in The Times of London failed to point out the active part the baron played in organising British relief during the Great Irish Famine. This criticism was voiced by John B. Standish Haly, the former secretary of the British Association for the Relief of the Extreme Distress in Ireland and Scotland (afterward known as the British Relief Association) in a letter to the editor. In this letter he stated that the British Relief Association had initially been organised in Baron Lionel’s own quarters in New Court, London, in December 1846, and that the Rothschild firm had donated £1,000. This sum, Haly claimed, was instrumental in the formation of the committee which collected upwards of £500,000 for the sister kingdom. The baron was active on a sub-committee that regulated purchases, shipments, and established depots all over Ireland and he sent several cargoes of wheat to Ireland at his own expense. Various monographs about the Rothschilds have subsequently quoted the letter, suggesting that the baron was the pivot of voluntary relief efforts for Ireland. However, official acknowledgement for what appears to have been extraordinary service to England and Ireland was never given. The final report issued by the British Relief Association is vague with regard to the organisation’s origins. It merely lists Baron Lionel Rothschild among other committee and sub-committee members. The house of Messrs. N.M. Rothschild & Sons appears in the organisation’s meticulous subscriber directory and is also credited as provider of two vessels for the shipment of relief goods.

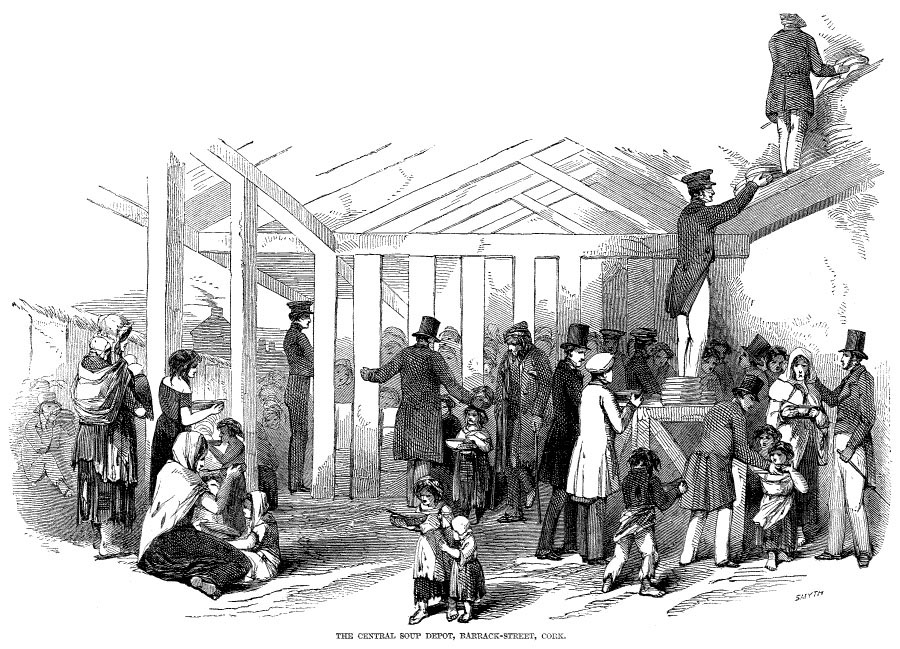

In fact, the British Relief Association altogether raised £470,041, for the most part in the early months of 1847, of which £391,700 was given to Ireland; the remainder went to Scotland, where there was also some food scarcity. The outcome of the solicitation was modest even by the standards of the time. Nevertheless, as a voluntary contribution to Irish famine relief it was unsurpassed, providing some alleviation of distress when suffering reached its first peak. However, those steps that resulted in the formation of this major voluntary relief effort have remained obscure.

Deputation from Skibbereen

While few papers can be found in the Rothschild archive pertaining to the British Relief Association or the Great Irish Famine, there is one document linking Rothschild to a deputation from Skibbereen that reveals how the British government directed the course of famine relief. It is an inconspicuous note dated 17 December 1846 from Irish-born philanthropist Stephen Spring Rice to Lionel Rothschild that is understandable only to the insider. In that letter, Spring Rice, who became the key person behind the British Relief Association, states that the Skibbereen delegation, Protestant ministers Richard B. Townsend and Charles Caulfield, informed him of having been cordially received by Rothschild. Spring Rice enclosed a memorandum written by Townsend and Caulfield, asking the baron if he could look at it and meet with him later that day. He explained that his urgent request was so that he might put the calling of a public meeting in London by the two Irish deputies in a ‘different light’.

At the end of November 1846, the Relief Committee of Skibbereen had sent Townsend and Caulfield to London to solicit funds for Irish relief. The initial idea had been for them to go ‘from city to city, and town to town, […] proceeding through the kingdom in that way’. The two began their mission by calling on the government, meeting with Sir George Grey, the Home Secretary, on 2 and 5 December. However, the discussion did not go well. Grey’s official response in a letter some days later, rather than holding out the prospect of increased government assistance, advocated private charity. Moreover, he declared the deputies’ request for a Queen’s letter in favour of famine relief to be premature.

‘Ireland herself should supply the remedy’?

Charles Trevelyan, the Permanent Secretary of the Treasury and principal architect of government relief to Ireland, also attended the first meeting of Townsend, Caulfield, and Grey. He concluded that what was needed in England was a general voluntary subscription under the superintendence of government officials in order to supplement ‘the necessary deficiencies of our Government Relief’. On 11 December Grey met with the Irish deputies for a third time, at which he courted them and gave advice on how best to solicit private charity. At about the same time, Grey appointed Spring Rice to assist the deputies and move the matter forward.

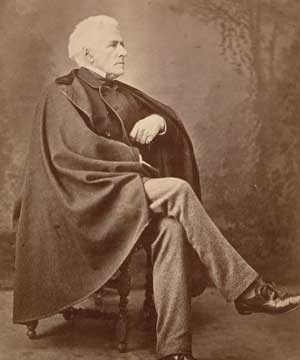

Above: Stephen Edmond Spring Rice—the key person behind the British Relief Association. (NPG, London)

Townsend and Caulfield promoted the idea of a public fundraising event that should also dispel what they considered misconceptions in the British public’s view of Ireland. Agreeing to call a meeting if the deputies could present him with a requisition to that effect, the Lord Mayor of London, Sir George Carroll, who was himself a native of Cork, suggested the most influential local personalities to whom they might appeal. It was in this way that Townsend and Caulfield approached Rothschild, and that Spring Rice was to write the letter revealing how the British government colluded against the two Irishmen’s call for support.

In the meantime, in a letter to a local newspaper, John Fitzpatrick, Skibbereen’s Catholic priest, gave a report of the deputies’ meeting with Rothschild that differed from that of Spring Rice. Drawing on a communication from the deputies, he claimed that Rothschild had described the famine as Ireland’s own national calamity, to which ‘Ireland herself should supply the remedy’. Although this was a widespread attitude in England at the time, and one to which the British government adhered throughout the period of the famine, the priest appears to have confused Rothschild’s reaction with that general resentment.

Rothschild’s ‘exertions in providing for the Irish’ downplayed

In his own letter to the editor, Townsend later explained that the deputies had only communicated the names of those who had treated them kindly, emphasising that the reception of the Irish deputation in the Rothschild house had been cordial. He added that he had been told that as a Jew Rothschild was prevented from taking a leading part in calling for a public meeting, as a demonstration of English sympathy with Ireland. If others had gone forward, Rothschild would have had no objection to joining. Some ambiguity remained in light of Townsend’s observation that he had found a positive disposition in various government departments to help Ireland if only others would step forward first, the difficulty being to get any ‘to take the lead in a cause so unpopular’.

The Irish deputies eventually gave up and withdrew as organisers of the campaign, apparently accepting Spring Rice’s conclusion that a public meeting might not serve their purpose. However, Lionel Rothschild took that role upon himself in two significant ways. On 29th December 1846 N.M. Rothschild & Sons was an early donor to what was to become the British Relief Association, setting an example by contributing the sum of £1,000. Moreover, all meetings held between 1 January 1847, when the organisation was formally established, and 6 January, when its first appeal was published, took place on the premises of Messrs. Rothschild at Swithin’s Lane in London, with Lionel Rothschild present at the majority of meetings. However, the British Relief Association’s public appeal and subscription list gave no prominent position to the Rothschild contribution, and it located the meeting of 6th January at the South Sea House, which was only used from the following day.

Lionel’s mother, Hannah Rothschild, could rightfully laud her son’s ‘exertions in providing for the Irish’. She also expressed her willingness to make a donation of her own if it were ‘necessary, what might be thought essential’. The general problem of nineteenth-century ad-hoc humanitarianism was that there was only a remote correlation between an actual state of emergency and perceived relief needs. In addition, the general disposition to provide aid tended to dwindle after a few weeks, as it did in the spring of 1847, although catastrophic conditions prevailed in Ireland for a number of years. Many authors have repeated the claim made in The Times addendum to Rothschild’s obituary that ‘throughout the period of extreme pressure Baron Lionel was indefatigable in his exertions’. With all due deference for the baron’s philanthropic stamina, this statement ignores the fact that practically all government and voluntary relief efforts during the Great Irish Famine assumed that only a single seasonal intervention was necessary. Rothschild’s patience in the matter was no greater than that of his contemporaries.

Above: Polish Count Paweł Strzelecki, the British Relief Association’s most highly praised agent in Ireland.

Irish voices excluded

The British Relief Association was in many ways a questionable body. In today’s terminology it was a ‘GONGO’—a governmentally organised non-governmental organisation. Its operations relied on the declaration of famine conditions, so that when that designation was officially withdrawn after autumn 1847, donations that had already dried up were further curbed. Also at issue was the government’s control over voluntary relief efforts as a buffer when it changed and downscaled official relief schemes in spring 1847. Spring Rice’s outline of principles for the British Relief Association has not been taken into account in previous research. It provided for the organisation to address gaps in official relief from its inception but was guided by the same harsh political economy and modernisation agenda that informed other government policies. A further problem was the government’s manipulation of fundraising practices and the exclusion of Irish perspectives. Apart from the case of Townsend and Caulfield, the outmanoeuvring of whom the Rothschild archive pointedly documents, at issue were also the aid appeals and reports by the British Relief Association that only quoted officials and the organisation’s representatives, but avoided communicating the voices of ordinary people in Ireland. By contrast, voluntary initiatives in North America and among Catholics around the world drew extensively on first-hand accounts by Irish people. The exclusion of Irish voices also affects the aid narrative in retrospect. The catalysing role of the deputies from Skibbereen is neglected, including their idea of publicising a Queen’s letter for Irish relief—something that was quickly adopted once the two had left London—and which became a major source of contributions to the British Relief Association.

Two more years into the famine, in a letter to his brother-in-law, Lionel Rothschild, Henry FitzRoy noted the silence of the English and the misleading newspaper accounts about Ireland. ‘As to the “comprehensive measures” of the Whig Government’, he wrote, ‘the idea is laughable. Which member of the cabinet is to furnish the comprehension?’ In fact, the overarching omission of providing relief that characterised the British approach was a calculated one. The underlying sentiment is trenchantly expressed in a letter preserved in the Rothschild archive, written by Count PawełStrzelecki, the British Relief Association’s most highly praised agent in Ireland: ‘There is nothing like a solemn and gigantic calamity embracing equally great and small in its sway, to bring people to their senses’. The ‘people’, in this instance, were the Irish, not the English. However, none of the reservations about the problematic role played by the British Relief Association has diminished Lionel Rothschild’s significance as one of the main facilitators of the greatest humanitarian effort of his time.

Norbert Götz is professor at the Institute of Contemporary History at Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden.

Further reading

N. Götz, G. Brewis & S. Werther, Humanitarianism in the modern world: the moral economy of famine relief (Cambridge, 2020).

C. Ó Gráda, Black ’47 and beyond: the great Irish famine in history, economy, and memory, (Princeton, 1999).

P. Gray, Famine, land and politics: British government and Irish society, 1843–50 (Dublin, 1999).

C. Kinealy, Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: the kindness of strangers (London, 2013).