‘The leading advocate of every murderer, ruffian and rogue villain’‘The leading advocate of every murderer, ruffian and rogue villain’

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2017), Volume 25The life and times of John Philpot Curran.

By Patrick Gageby

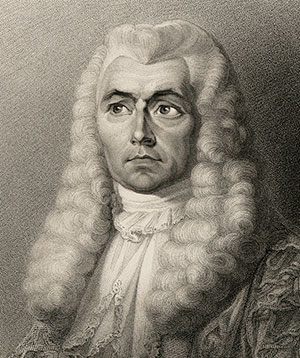

Above: Portrait of John Philpot Curran (1750–1817), Orator and Statesman, by Thomas Lawrence. (NGI)

Curran was born in 1750 in Newmarket, Co. Cork, into a modest Church of Ireland family. He probably understood Irish. A local gentry family paid for his education to secondary level and thereafter at Trinity College, Dublin, where he obtained a scholarship in 1767. He sat dinners in Middle Temple in London, and was called to the Irish Bar in 1775. He married young. He practised and did well on the Munster circuit, and achieved fame in 1780 in a civil action for assault in which he was counsel for a local Catholic priest who sued Lord Doneraile, an influential landed proprietor. Curran secured a judgement for 30 guineas—no mean feat when juries were drawn from the Protestant and landed classes.

Curran was a gregarious person at a time when drinking was rife at all levels of society. He became prior of St Patrick’s Society, more commonly known as the ‘Monks of the Screw’ (as in corkscrew). Its members were mainly liberal thinkers with a very strong representation of MPs and barristers. Curran composed their charter song.

A member of two of the best clubs in Ireland

In 1783 he entered the Irish parliament for Kilbeggan, and associated with the ‘patriot’ elements in the House. He was now a member of two of the best clubs in Ireland—the Bar and parliament. The Bar was one area where men of little wealth but some ability might progress rapidly. His practice flourished, and he moved into a substantial house in Ely Place, close to the lord chancellor, John Fitzgibbon, originally a friend but now a foe.

Curran’s speeches were full of wit, imagination and plenty of humour, good or wicked, as the need arose. Some of his utterances were subsequently adopted and became universally glossed. In July 1790, before the privy council, he coined the phrase ‘The condition upon which God hath given liberty to man is eternal vigilance’, and thus ‘Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty’.

By the 1790s Ireland was beginning to heat up. There were pressing claims for Catholic emancipation, but also agrarian and sectarian disturbances. The French Revolution was an example to many. From 1794 onwards, many defendants without means to pay were defended by Curran. Francis Higgins (a.k.a. the ‘Sham Squire’), who ran an intelligence network, told Dublin Castle that funds were regularly raised at meetings for such accused and that Curran was ‘the leading advocate of every murderer, ruffian and rogue villain’. Criminal defence was not seen as respectable. Indeed, Curran, because he was a King’s Counsel, had to pay a fee to the Crown to defend. Prosecutions for criminal libel were a handy vehicle for the defence to publicise—indeed, sometimes justify—dangerous views such as emancipation, parliamentary reform, democracy, liberty, free speech, etc. Across the water there were prosecutions for publishing revolutionary writings, such as Paine’s The rights of man.

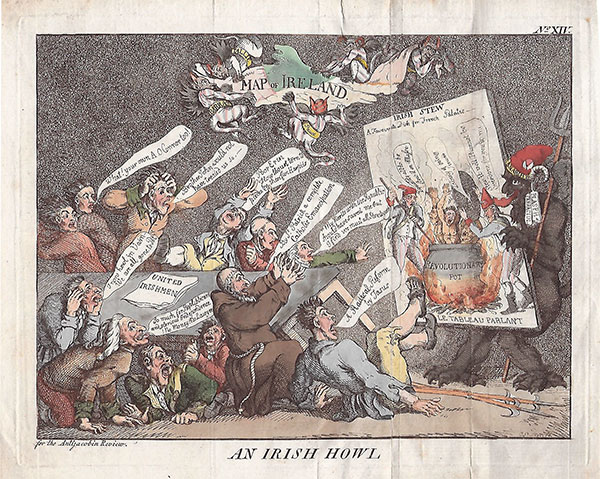

Above: ‘An Irish Howl’—from the Antijacobin Review, 1 March 1799. On the extreme right the Devil holds up a ‘TABLEAU PARLANT’ of two French soldiers boiling a ‘REVOLUTIONARY POT’ containing three naked Irishmen shrieking for mercy, which terrifies twelve Irishmen grouped around an upturned table, including (bottom left-hand corner) a lawyer (reputed to be Curran) saying, ‘So much for Republicani[sm] and glorious Independence! No Money! No Lawyer!’ (British Museum)

United Irish defence team

A team came into being to defend the United Irishmen and the like—mainly Curran, usually with Leonard McNally and occasionally with Thomas Addis Emmett, John and Henry Sheares, William Sampson, ‘Pleasant’ Ned Lysaght and others. Matthew Dowling, a leading United Irishman, was frequently the solicitor. The Sham Squire told Dublin Castle that Dowling had a room rented opposite Green Street court room, where witnesses were cleaned up and coached. Major Sirr, the de facto police chief, was alleged to have had a similar academy, accommodated in Dublin Castle, where the pupils were informers. Most of the state trials of the 1790s involved the use of informers. Curran’s cross-examinations of such people have passed into history and are reported in Howell’s State trials. These transcripts are a priceless source of social history.

By the mid-1790s, Curran was the leading criminal and civil advocate — except in matters before Lord Chancellor Fitzgibbon. Notwithstanding that, Curran prospered and kept a country seat in Rathfarnham—the Priory, so named on account of his former position as the prior of the Monks of the Screw. Here he entertained, and here his five children could play in the extensive grounds. In 1792 his twelve-year old daughter Gertrude died after falling from a window in the house; she was buried in a small vault in the lawns. Friends and enemies alike noted Curran’s melancholia, which might today be diagnosed as depression or even bipolar disorder. His friends attributed this to Curran’s being cuckolded by a Revd Mr Sandys. Curran foolishly sued him for the civil wrong of criminal conversation, i.e. seduction, on St Valentine’s Day 1795. His old friend Lord Avonmore presided. Curran made a fool of himself, as he had to admit to his own extra-marital liaisons. He was awarded a derisory figure of £50 damages and 6d costs. He never met his wife again. This imprudent litigation would not advance his chances of promotion. He thereafter established a relationship with a Tipperary widow, Marianne Fitzgerald, by whom he had two sons—John Philpot, b. March 1798, and Henry Grattan, b. February 1800. Both practised as barristers and went on to inherit the greater part of Curran’s fortune.

Above: Curran as master of the rolls—when the Whigs came into power in 1807 he was disappointed to get the office, a well-paid sinecure but lacking prestige. (NGI)

The trial of William Orr in 1797 was ostensibly unexceptional. Curran and Sampson defended; Lord Avonmore was the judge. Orr was charged with administering the United Irishman oath to two soldiers, a capital offence. The jury was out for eleven hours, with a verdict of guilty but a recommendation for mercy. Curran tried to set aside the verdict, calling evidence of whiskey-drinking by the jurors and evidence casting doubt on one of the soldier witnesses. He lost. Orr’s execution was twice postponed but no mercy was forthcoming. He was executed on 14 October 1797.

The Orr case, rightly or wrongly, became a byword for injustice and the cruelty of government, as did the catchphrase ‘Remember Orr’. The Press, an organ of the United Irishmen, didn’t hold back, and Peter Finnerty, its printer, was prosecuted in December 1797 for seditious libel. To that charge the truth was not a defence. Curran, McNally, Henry and John Sheares and Sampson appeared for the defence and, in doing so, called Lord Yelverton and Edward Cooke from Dublin Castle, to show that the government declined to commute the sentence. Curran’s closing address was a trenchant defence of free speech. Finnerty was convicted, sentenced to imprisonment and ordered to stand for an hour in the pillory in Green Street.

As the year 1797 closed, Curran and others resigned from parliament, but his reputation was at its height. Rebellion was in the air, and the French were expected. Throughout the 1790s Bastille Day was marked in Dublin’s Liberties with bonfires and singing. While the United Irishmen were organising, so was Dublin Castle: when the informer James O’Brien appeared as a witness in Green Street on 16 January 1798 to give evidence against Patrick Finney for high treason, he had a fairly common story to tell. Passing a pub in Thomas Street, he had met Finney and others, had drinks, took the United Irish oath, went to meetings, informed the authorities, was promoted and was then present when Major Sirr raided a meeting. Curran cross-examined almost entirely on O’Brien’s credibility—for instance, that O’Brien impersonated a revenue officer and extorted money from unlicensed grocers, that he borrowed and owed money, had blackmailed a Mrs Moore and, most wonderfully, had passed on a recipe for converting copper into silver coin (that recipe you will find in the report). Curran spoke of O’Brien as ‘a cannibal informer, greedy after human gore, with fifteen other victims in his sights’. After fifteen minutes the jury acquitted Finney, and the case against the remainder of the accused was dropped. Curran’s speech was widely circulated. O’Brien was, unsurprisingly, universally execrated. Ballads were written about him, and two years later he was convicted of a murder in Steevens’s Lane and executed, notwithstanding the efforts of Major Sirr. One of the ballads has the macabre title ‘Jimmy O’Brien’s Minuet as performed at No. 1 Green Street’—the place of execution outside Newgate Gaol.

Sheares brothers

After the Finney trial there were few acquittals, and the trials of the 1798 Rebellion bore heavily on Curran. The arrest of the Leinster Directory of the United Irishmen in Oliver Cromwell Bond’s house in March caused barristers Henry and John Sheares to move up on the military side. They foolishly thought that they had persuaded Captain Armstrong to defect with his men to their cause. Armstrong did not defect; rather he alerted his superiors and was interviewed by Castlereagh and Edward Cooke of the Castle. The Sheares brothers were arrested and moved from the Bar to the dock. Applications to postpone the Sheares’ trial were made, perhaps in the hope that Armstrong might perish on active service—indeed, he was extremely active in Wexford. Curran defended Henry Sheares, but the case against both brothers was strong, and John Sheares had foolishly, and optimistically, written a proclamation to be published when all was won. That was read to the jury. Even Curran’s abilities could do little against such a tidal wave of evidence. The court sat throughout Thursday 12th and into the morning of Friday 13th, when the jury retired for seventeen minutes and returned with their guilty verdicts. On Bastille Day both were executed. A fading monument to their memory sits in the centre of the playground in Green Street where Newgate once stood, and the vaults of St Michan’s Church holds their bones.

Some connections in and around this trial are worth noting. The presiding judge at the trial, J. Carleton, knew the Sheares’ parents. Curran knew everybody, including many members of the jury. The Sheares brothers’ father had moved amendments to the Treason Act in the Irish parliament in 1765. John Sheares appeared in the trial of Finnerty in December 1797. He had also been Leonard McNally’s second in a duel with Sir Jonah Barrington. Barrington claims (and Barrington was an unreliable historian) to have secured a pardon for Henry Sheares and made haste to Newgate, but arrived too late. Fitzgibbon, the lord chancellor, knew everybody, did not like Curran and may have courted Henry Sheares’s wife before she married. McNally had been a spy since early 1795 and was managed by Pollock, a Crown solicitor, who also handed on McNally’s information and letters to Edward Cooke, who was a defence witness in the Finnerty case.

On Monday 16 July the trials resulting from the raid on Oliver Bond’s house started with that of John McCann, with Curran and McNally for the defence. Over eight days, four long capital trials were carried out. During Curran’s final speech in Green Street there was a hostile tumult in court, perhaps the clashing of the arms of the military. Curran is said to have turned to the hostile crowd and stated, ‘You may assassinate, but you shall not intimidate me’. The court said: ‘We will take care, with the blessing of God, that you shall not be interrupted’. After seven minutes Bond was convicted.

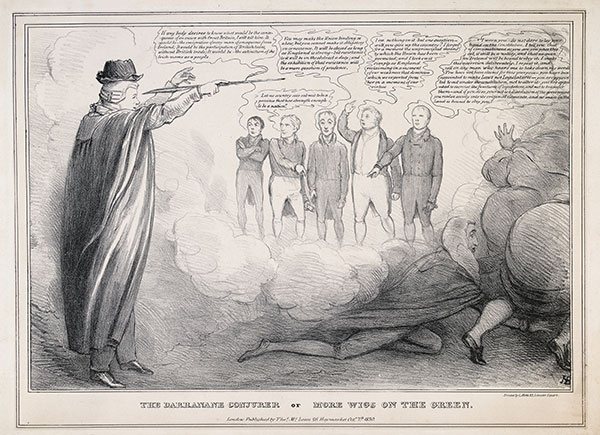

Above: ‘THE DARRANANE CONJURER or MORE WIGS ON THE GREEN’ by John Doyle, 7 October 1830—Daniel O’Connell conjures up ghosts in support of Repeal, including Curran (left), who says: ‘If any body desires to know what would be the consequences of an union with Great Britain, I will tell him. It would be—the emigration of every man of consequence from Ireland; It would be the participation of British taxes, without British trade; It would be the extinction of the Irish name as a people.’ (NGI)

Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet

The judicial system was sated and Curran was exhausted; he went to England to recuperate, until the capture of Wolfe Tone off Donegal in November 1798 brought a new cause. Tone was convicted by court martial, sitting near Arbour Hill, but Curran made an emergency application to Lord Kilwarden, previously attorney general, for a habeas corpus, on the grounds that martial law and courts martial were incompatible with the ordinary courts. The government feared such an argument.

Sarah Curran’s relationship with Robert Emmett and the aborted rebellion of 1803 are well known. The Priory was searched and the Curran family were under suspicion. Lord Kilwarden, who had been a moderating influence as attorney general, had been piked to death in Thomas Street. Curran defended some of those indicted. Unusually, in February 1804 he, along with McNally, appeared for the Crown in Green Street in a charge of conspiring to murder the parish priest of Rathfarnham—perhaps a token to demonstrate state confidence in Curran.

When the Whigs came to power in 1807, Curran was disappointed to get the office of Master of the Rolls, a well-paid sinecure but lacking prestige. He moved his town house to St Stephen’s Green, which he sold on his retirement in 1814, along with his furniture, pictures and 100-dozen ‘of very superior old port wine’. In his last years Curran travelled much and enjoyed the dinner-party circuit, chiefly in England. He was known to Shelley, Byron and Madame de Stäel. He died in London on 14 October 1817, exactly twenty years after Orr’s execution. His remains were interred in Paddington Church. Peter Finnerty, printer, was a mourner. In 1834 Curran’s remains were removed to Glasnevin Cemetery, where the imposing granite sarcophagus bears just one word, ‘Curran’.

Remember Curran!

Patrick Gageby is a Senior Counsel.

FURTHER READING

W.H. Curran, Life of Right Honorable John Philpot Curran (New York, 1855).

T.B. Howell (ed.), Cobbett’s complete collection of state trials, Vols 25–29 (London, 1809–26)