Language politics

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2018), Volume 26Comparing Irish nationalism and Zionism.

By Aidan Beatty

Above: A 1948 Israeli Ministry of Education and Culture poster showing a sign with the word ‘Hebrew’ pointing towards a blue sky, green fields and an agricultural settlement, opposing signs that have foreign languages on them pointing towards darkness and the barbed-wire fences of death camps. (Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem)

‘There was a bulky, fat, slow-moving man whose face was grey and flabby and appeared suspended between two mortal diseases; he took unto himself the title of The Gaelic Daisy. Another poor fellow, whose size and energy were that of the mouse, called himself The Sturdy Bull.’

Ó Cúnasa goes on to describe a Gaelic Leaguer ‘a bhí cíúin ceansa neamhurchóideach, thug sé air féin “An Pocán Meidhreach”, d’ainneoin nár phoc sé aoinne agus nach raibh sé meidhreach’ (‘who was quiet, docile, innocent, gave himself the title “the Merry Billy-Goat”, notwithstanding that he had never hit anyone and was not merry). There is a bilingual play on words here between pócan (a male goat) and phoc (past tense of poc, to hit a ball). All the pretensions of this innocent young man to be ‘the Merry Billy-Goat’ were grossly undermined by the fact that he never phoced anyone! Vulgarities, as well as problems of easy translation, are perhaps why this Merry Billy-Goat is omitted from the standard English version of An Béal Bocht/The Poor Mouth.

As with so much else in this novel, Myles na gCopaleen’s description of the actions of Gaelic League members is in equal parts sarcastic and bitingly perceptive. One of the most important organisations in both the cultural revival of the late nineteenth century and the political ferment of the early twentieth, the Gaelic League was heavily invested in practices of self-invention and of imagining a more perfected version of Irish manhood. And, as An Béal Bocht pointed out, names were a central part of this.

Above: President of the Gaelic League Douglas Hyde—in 1899 he argued that the nation had become ashamed of their Irish names. (National Folklore Collection)

Name-changing

Patrick Ingoldsby, one of the main organisers of the Gaelic League’s annual language parades, became Pádraic Mac Giolla Iosa (lit. Patrick, son of the servant of Jesus). John Leslie, a landed nobleman, Oxford graduate and first cousin of Winston Churchill, became Shane Leslie, sometimes spelling it ‘Seaghan Leslaigh’. Percy Fredrick Beazley, the son of Irish immigrants in Liverpool, became Piaras Béaslaí—Gaelic Leaguer, Volunteer, pro-Treaty Sinn Féiner and Michael Collins’s hagiographer. Patrick Pearse, son of a Birmingham stonecutter, became Pádraic MacPiaras, as well as adopting pen-names redolent of a recovered Gaelic ideal, such as ‘Colm Ó Conaire’ and ‘Cuimin Ó Cualain’. Nor was it only men who changed their names. One of the few leading female figures of the early Gaelic League decided, after her first visit to the Aran Islands in 1898, that she would rather be known as Úna Ní Fhaircheallaigh instead of by her birth name, Agnes Mary Winifride Farrelly.

Name-changing was a complex practice, capable of expressing a number of quite different ideals. Hyde famously adopted the pen-name An Craoibhín Aoibhinn (‘the Pleasant Little Tree-Branch’), which points to a far less militarised, less forceful vision of a de-Anglicised scholarly identity. Changing one’s name was a common means of reinforcing ownership over one’s own identity and of expressing a purely Gaelic subjecthood, as opposed to the inchoate nature of being inwardly Irish but with an externally English label. This was in fact a quite common practice in various national contexts across Europe. As Eric Hobsbawm comments, ‘The generations before 1914 are full of great-nation chauvinists whose fathers, let alone mothers, did not speak the language of their sons’ chosen people and whose names, Slav or Magyarized, German or Slav, testified to their choice’.

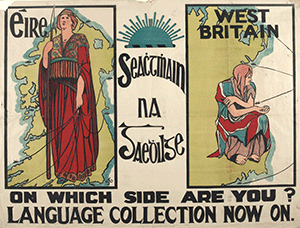

Above: ‘On which side are you?’—Gaelic League poster, 1913. (NLI)

Zionism

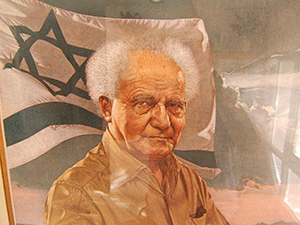

Above: David Grün, a native of rural Poland, moved to what was then Ottoman Palestine in 1906 and promptly became David Ben-Gurion.

David Grün, for instance, a native of rural Poland, moved to what was then Ottoman Palestine in 1906 and promptly became David Ben-Gurion. He was later able to claim, with a remarkable logic, that ‘I have forgotten that I am Polish’. His successor as Israeli prime minister, Moshe Sharret, born Moshe Shertok, had also abandoned a Yiddish name along with a diasporic past. And one Goldie Myerson (née Goldie Mabovitch), a native of Belarus, adopted the more suitably Hebraic Golda Meir after moving to Palestine in 1921. Adopting new Hebrew names, and expecting others to do the same, was a central part of negating the diaspora and forging a new Israeli identity.

Masculinity

In Zionism this also had a distinctly masculine aspect. The Israeli poet Avot Yeshurun, for instance, abandoned his birth name, Yechiel Perlmutter (which, as well as advertising his diasporic and Yiddishkeit origins, was also a name with clearly feminine overtones). His new name, which can mean either ‘fathers are watching us’ or ‘fathers of the people of Israel’, was thus part of his new masculine Zionist identity. Another instructive case is that of ‘the first Hebrew child’, Ben-Tsiyon Ben-Yehuda, son of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. The elder Ben-Yehuda was a central figure in the history of modern Hebrew, albeit one whose importance has perhaps been exaggerated. He was born Eliezer Yitzhak Perlman, but upon moving to Ottoman Palestine adopted a name with less obviously Yiddish and mercantile origins; his new name translates as ‘son of Judea’. His son, who grew up barred from speaking any language but Hebrew, was given a name meaning ‘son of Zion’, reflecting his new identity rooted in the soil of the biblical homeland. In adulthood, however, he changed his name to Itamar Ben-Avi, meaning ‘date tree [a Zionist symbol] son of my father’. Ben-Avi can also mean ‘son of A.B.Y.’ (his father’s initials). Both father and son were clearly involved in a process of self-invention, creating new names and new ideals for men rooted in the soil of a Hebrew-speaking homeland.

As the Israeli historian Amos Elon notes, the early Zionists had ‘a proclivity to redefine themselves with names that denote firmness, toughness, strength, courage, and vigor’, such as: Yariv (‘antagonist’), Oz (‘strength’), Tamir (‘towering’), Bar Adon (‘son of the master’ or ‘masterful’), and even Bar Shilton (‘fit to govern’). Much like in the revival of Irish, Zionists, by reviving Hebrew, sought to prove their masculine strength and, more importantly, to prove to themselves and others that they were indeed Bar Shilton.

That Hebrew revivalists engaged in a similar practice to their Irish contemporaries is unsurprising. Both drew on a similar set of ideas about history and national revival, and both sought to counter similar stereotypes about deformed language as a sign of a deeper national deformity. Even the titles of two of the most important Hebrew and Irish revivalist publications are remarkably similar: HaShachar (‘The Dawn’), edited by Peretz Smolenskin in Russia in the 1870s and 1880s, and the Gaelic League’s Fáinne an Lae (‘The Dawning of the Day’). Both titles suggest a return to some lost national ideal after a long night (or nightmare?) of exile or foreign control.

Anxieties about Yiddish

In general, anxieties about the lack of a single shared Jewish language expressed a set of deeper fears about Jews’ racial ambiguities. At the forefront in these anxieties was Yiddish. This language, with its diverse roots in German, Hebrew and various Slavic languages, seemed to bear out nineteenth-century racist European notions that a people speaking a hybrid language were somehow inferior and incapable of clear, intelligible and sophisticated thought. As with so much else in Zionism, this linguistic anxiety bore more than a passing resemblance to contemporary anti-Semitism. Sander Gilman, a prominent scholar of Jewish history, identifies this as a linguistic racism: ‘The Other cannot ever truly possess “true” language and is so treated’. The allegedly corrupt nature of Jewish discourse (whether in an indigenous tongue or in the use of gentile languages by Jews) was an anti-Semitic accusation with a long pedigree, and elsewhere Gilman observes, with a note of resignation, ‘Is it of little wonder that modern Hebrew developed a set of sociolinguistic practices which were the antithesis of this ancient stereotype?’ Many Zionists certainly felt that Jews were linguistically flawed and saw Hebrew as the means to correct this.

Ben-Gurion, for instance, while pragmatically accepting that other languages might have to be used within the Zionist movement, felt that only Hebrew could guarantee ‘our future as a healthy nation, united in its land’. A poster produced after 1948 by the Israeli Ministry of Education and Culture promoted the use of the national language by talking of ‘not seventy languages, one language, Hebrew’ (lo shiv’im lashon, lashon achat, ivrit), a biblical reference to the 70 nations of the postdiluvian world. Thus, in opposition to a confusing Babel of tongues, Zionism would mark a return to being a nation ‘of one language and of common purpose’. With unalloyed harshness, a poster (p. 44) from the Israeli Army’s cultural unit depicted European languages such as Hungarian, Romanian and Polish as a multitude of signposts that lead to the darkness of the death camps. In contrast, Hebrew was a single signpost pointing to a bright, bucolic vision of Palestine. ‘The language serves to create a single heart for all parts of the nation [ha-lashon ba’ah livro lev echad le-col chelekei ha-umma]’, the culture ministry declared, in a quote ascribed to the Israeli national poet, Chaim Nachman Bialik.

Fitting with what Eric Hobsbawm has said about early twentieth-century debates over racial purity and the contemporary nationalist focus on linguistic purity, Zionists saw Yiddish, and the diversity of diasporic tongues in general, as signs of racial indeterminacy. Not unlike the Irish nationalist concern that Béarlachais was a living symbol of a worryingly diluted national identity, Yiddish became a signifier that Jews were everywhere a minority and nowhere a cultural, linguistic or politically sovereign majority. Echoing such ideas, Yosef Chaim Brenner, novelist and prominent Zionist, conflated the speaking of Yiddish with an inability to function normally and ‘the worst aspects of diasporic life’. Even more blatantly, the poet Avraham Sholonsky spoke of the ‘catastrophe of bilingualism’ as being a form of national tuberculosis. Hebrew would thus be the obvious national cure. As with the Gaelic League, Hebrew revivalists saw their project as one of reconnecting to a heroic past and to a lost national and linguistic purity, and thus as a means of ameliorating their nation’s contemporary weaknesses and racial indeterminacy.

There were certainly major differences between Irish nationalism and Zionism: Irish nationalists sought to build a state and a national culture in the land in which they already lived, while Zionists set their sights on a biblical ‘homeland’ that few of them had even directly experienced. Zionism was much more an overt product of European colonialism than Irish nationalism, as evidenced by Zionism’s clash with the Palestinians, who themselves were coming into a national consciousness by the early twentieth century. Nevertheless, in terms of their attitudes towards race, their attempts to prove that they were ‘real’ Europeans and the role that revivified ancient languages played in all that, these two national ideologies that emerged on the fringes of Europe had some serious points of comparison.

Aidan Beatty is an Irish Research Council postdoctoral fellow at Trinity College, Dublin.

FURTHER READING

Almog (trans. H. Watzman), The Sabra: the creation of the New Jew (Berkeley, 2000).

Banerjee, Muscular nationalism: gender, violence, and empire in India and Ireland, 1914–2004 (New York, 2012).

Beatty, Masculinity and power in Irish nationalism, 1884–1938 (London, 2016).

Sisson, Pearse’s patriots: St Enda’s and the cult of boyhood (Cork, 2004).