Kindred Lines

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2015), Volume 23Estate records as a source for family history

By Fiona Fitzsimons

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries c. 95% of productive land in Ireland was in estate ownership. The number of families that owned these estates was tiny. They derived great authority and wealth through their monopoly on landownership. Every estate was organised and run as a business to support the landlord and his family, and consequently gave employment to the local community. The estates were the local economy, and some of them even used their own ‘tokens’, as distinct from legal tender, to purchase goods and services on the estate. Estates also kept administrative records, many of which survive to the present day.

Rentals

The main evidence you will find includes:

• Names of all tenants and occupiers, including small farmers and landless labourers.

• Size and address of their landholding.

• Amount of rent due, whether in cash, services or goods.

• Rent was collected twice yearly, on pre-set ‘gale days’, and rentals will record whether the rent was paid or not. In almost every rental, landlords often allowed rents to accrue, especially in years where bad weather led to a reduced crop.

• Type of tenancy, i.e. lease for lives, annual or ‘at will’.

• Rentals will sometimes contain comments and observations made by the landlord or his agent about individual tenant families.

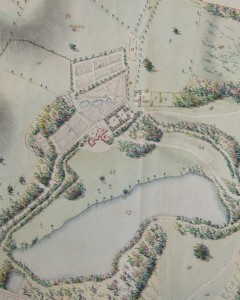

Detail of a map of Ballyfin demesne, Co. Laois, c. 1814. Estate maps are a dynamic source that can sometimes allow you to track your ancestors’ tenancy on the same estate for many generations. (Brigidine Sisters)

Surveys and maps

Estates usually kept their own estate maps and ‘marked up’ all land set to rent to keep track of who was on the land. Estate maps are a dynamic source that can sometimes allow you to track your ancestors’ tenancy on the same estate for many generations. Between 1700 and 1845 an estimated 600 estate villages and 150 estate towns were created or modernised by landlord interests. You will find the original surveys, architectural plans and maps ‘marked up’ to show tenant occupancy.

Leases

Deeds of lease are one of the richest sources for family history. A lease for life was a long lease, to encourage substantial tenants to settle on an estate. The lease was usually for a ‘set term’ or for ‘three lives’ named in the deed of lease. A deed of lease often allowed the tenant to replace any of the original names or ‘insert a new life’ on payment of a fine, ad infinitum. Where names are recorded in a lease, they will usually include the principal tenant and his siblings or healthy children, thought likely to live until the lease was due to expire. The exact relationship between all lives named in a lease is often specified.

Business interests

Most estates were based on agriculture—food and flax for linen. Some estates with natural resources developed other business interests. For example, the Murray-Stewart estate has records of the fishing port and borough of Killybegs, Co. Donegal, and the Prior-Wandesforde estate papers include detailed records, including some pay-books, for the Castlecomer collieries in County Kilkenny.

Title-deeds and legal papers

As a rule of thumb these records relate to many generations of the landlord’s own family. Title-deeds are the evidence of legal ownership. Other family deeds often include family settlements: annuities for an unmarried daughter or sister; a cash sum paid to a younger son who had reached the age of majority or enlisted in the armed forces; mortgages on land to pay for a daughter’s marriage settlement; wills and grants of probate.

Where will you find estate records?

In the late nineteenth/early twentieth centuries, when the large estates were broken up, there was no plan for dealing with the historic records and many were destroyed. Tracking down what survives will involve some research. The largest deposits are in Dublin’s National Library and the Land Commission, and in the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland in Belfast. Some records can be found in the relevant county library.

Fiona Fitzsimons is a director of Eneclann, a Trinity College campus company, and of findmypast Ireland.

Further reading

T. Dooley, Sources for the history of landed estates in Ireland (Dublin, 2000).

Landed estates database, NUI Galway, http://www.landedestates.ie/.