KINDRED LINES: Lunatic asylum records

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2017), Volume 25By Fiona Fitzsimons

Early attempts to make medical provision for the mentally ill in Ireland were very disjointed. The earliest asylums for the insane were in the cities of Dublin and Cork, under the aegis of the House of Industry. As early as 1728 the Dublin House of Industry set aside cells for the insane on the St James’s site, and in 1772 further cells for ‘curable lunatics’ were provided on the North Brunswick Street site.

In 1746 the legacy of Jonathan Swift, dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, led to the foundation of St Patrick’s Hospital as a private asylum. By the last quarter of the eighteenth century this piecemeal approach to providing for mental health was gradually imploding under the weight of Enlightenment ideas. There was a growing realisation that the state could play a role in social reform.

Between 1765 and 1772 the Irish parliament passed legislation to establish a system of infirmaries in every county in Ireland, using public funds. By the last quarter of the eighteenth century there was a more systematic approach towards developing hospitals. In 1791 an asylum for Cork was established, and in 1814 the Richmond Asylum opened as a national asylum in Dublin; both institutions operated under their respective Houses of Industry.

In 1821 the Lunacy (Ireland) Act provided for the establishment of a network of district lunatic asylums across the island of Ireland. The first were opened in Armagh (1824/5), Limerick (1827), Belfast (1829), Londonderry (1829), Carlow (1832), Ballinasloe/Connacht (1833), Maryborough (1833), Clonmel (1835) and Waterford (1835). The existing Richmond (Dublin) and Cork asylums were incorporated into the system in 1830 and 1845 respectively. Between 1846 and 1847 the Irish government oversaw the redistribution of districts and established new asylums in Kilkenny (1852), Killarney (1852), Omagh (1853), Mullingar (1855) and Sligo (1855). Other asylums built in the immediate aftermath of the Famine were in Donegal (1866), Castlebar (1866), Enniscorthy (1868), Ennis (1868) and Monaghan (1869).

In the 1820s a person could be committed directly to an asylum on the evidence of another. The Dangerous Lunatic Act 1838 meant that a person could be arrested if deemed to be a danger to him/herself or others, and committed first to jail and then to the district lunatic asylum. Some of the few mental health records that are currently open to researchers are the Convict Reference Files, part of the Transportation records (CSORP) held in the National Archives. Some of these files relate to the confinement of lunatics in prison and their subsequent transfer to asylums. The records cover the years from 1843 to 1869. They contain registers of prisoners committed to asylums, at the end of each year, because they had gone mad and/or tried to kill themselves. As a rule there is little or no information about relatives, but there is information about the incidents that led to their committal.

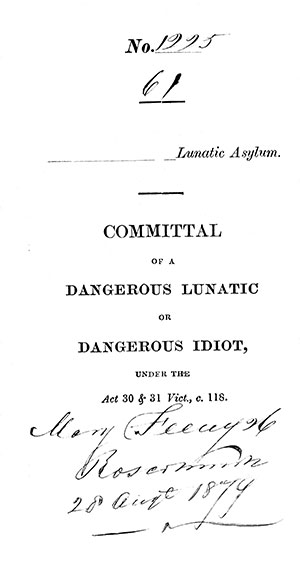

Above: The committal form of Mary Feeney, Co. Roscommon, to the Connacht (Ballinasloe) Asylum, 27 August 1879.

Unusually for historical records in Ireland, those of the asylums have a remarkably good rate of survival. Many hospital/asylum records remain on site; while this has contributed to their survival, most have not been conserved or listed. The National Archives has accessioned some, including Ballinasloe/Connacht and records of the Richmond, including Grangegorman and St Ita’s, Portrane. Other records have been accessioned by their county archives—the Carlow Asylum records are held in the Delaney Archive, the Limerick Asylum records in the Limerick City Archives, etc. Asylum records in Northern Ireland are mainly deposited in the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland.

So what do these records contain of relevance to the family historian? Records are extensive and include admission and discharge registers, and patient registers with the patient’s name, age, previous residence (possibly a jail or workhouse), place of birth, marital status, religion, occupation, literacy and education, next of kin, and whether the patient recovered or died within the asylum. Some case-books from the late nineteenth century (Richmond and Carlow) include patients’ photographs. Particularly good are the committal reference forms, which provide three relatives’ names. These records contain incredibly powerful material, of people living in adversity and the conditions that usually precipitated their admission to hospital.

Unfortunately, these records are not accessible, except for scholarly research or where authorisation has been obtained from the institutions concerned. Any queries should be addressed to the Surveyor of Business Records, National Archives, Bishop’s Street, Dublin 8.

Fiona Fitzsimons is a director of Eneclann, a Trinity campus company, and of findmypast Ireland.