Keeping Celtic Studies alive in Germany

Published in Issue 2 (March/April 2021), News, Volume 29Celtic Studies used to play an important part in Germany’s academic landscape. Today the discipline is considered rather exotic. Similarly, little attention is paid to Irish literature. In defiance of this, academics based in Germany share how and why they are keeping Irish heritage alive.

By Laura Patz

Marthe-Siobhán Hecke wearing the T-shirt of the University of Bonn’s Celtic Studies student association.

It must be tiring sometimes. Most new acquaintances struggle to pronounce her first name. Letters and subscriptions that she receives are often addressed to Mr Hecke. And after she was born, German authorities even declared her name invalid. The Irish Embassy had to confirm in writing that Siobhán was a common first name.

German Marthe-Siobhán Hecke had to take a little detour until she found her academic ‘happy place’ studying English and Celtic Studies. And only then did she finally start to embrace the ‘wild’ part of her name. The University of Bonn, where Marthe-Siobhán studied and is now working on her doctorate, is the only third-level institution in Germany that offers a bachelor’s degree in Celtic Studies. Moreover, there is a certain disregard between the English and the Celtic Studies departments. Since it isn’t possible to do a doctorate in Celtic Studies in Bonn, Marthe-Siobhán is writing about Scotland and a topic somewhat related to Celtic Studies, ‘so no one gets mad at me’.

The University of Marburg offers a master’s in Celtic Studies but, other than that, the subject has seen a significant decline in academic popularity.

‘And yet it used to be a big thing in Germany,’ explains Marthe-Siobhán, ‘particularly since Rudolf Thurneysen, who researched and wrote extensively about Old Irish Grammar.’ The Swiss Thurneysen is considered one of the most influential Celticists worldwide. Between 1913 and 1923 he taught at the University of Bonn and thereby shaped the institution’s Celtic Studies department. Bonn’s Celtic Studies students can decide which modern Celtic language they want to focus on: Irish, Welsh, Scots Gaelic or Breton. Those who opt for Irish even get to translate ogham.

Dr Gisbert Hemprich, who teaches Celtic languages and literature in Bonn, points out that Irish has been a literary and scientific language since the early Middle Ages. ‘A language that has such a strong foundation must be learned by anyone who is serious about Ireland’, he says. Marthe-Siobhán agrees and cannot stress enough how important she considers what her work stands for: the preservation of Irish heritage for present-day understanding.

To her, it is important to equip non-Irish people with a certain awareness of and respect for the country. ‘Böll’s Irish Journal, the Cliffs of Moher and Dingle … wow! I know everything now’, she says, mocking some German visitors to Ireland. Those who ignore a country’s language are leaving out major aspects of cultural identity.

But it’s not only the Irish language that takes second place to English. ‘It’s not that you have to know where every author’s from but just that sometimes a little bit of context does help to open some people’s eyes’, adds Irishman David Moroney, who teaches Irish literature in Bonn. He is convinced that the subject is not given its due in literary studies. ‘Often, departments are divided into linguistics and literature’, he says, going on to explain how some universities tend to neglect Irish literature. ‘Literature is very often British or American, or sometimes Australian, like in Cologne.’

Prof. Katharina Rennhak, president of the European Federation of Associations and Centres of Irish Studies (EFACIS) and teacher at the University of Wuppertal, knows more about the reasons behind this. According to her, many rather small German universities once focused on Irish Studies. ‘What used to be a unique selling point started to fade from the late eighties onwards as professors interested in Ireland retired.’

Nevertheless, there is a critical mass of individuals and universities holding on to their appreciation of Irish literature, she says. What connects Wuppertal to Ireland’s literary scene is its Walter Macken archive. Macken’s work was disregarded for a time. Now, from a historical distance, the playwright is being rediscovered, Rennhak explains:

‘Back in the seventies, two professors of Irish Studies from Wuppertal were known all over Ireland. They regularly hunted for Irish writings in antiquarian bookshops. It was in a shop in Galway where acquaintances of Macken’s widow approached them in 1977. His work then became the property of the University of Wuppertal. Ever since, the university has maintained an above-average focus on Irish Studies.’

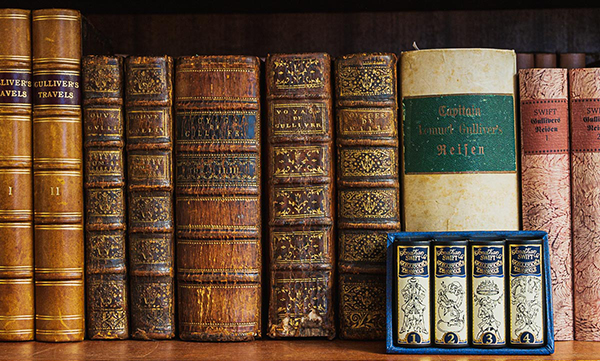

A few items from among the 10,000 bibliographic entities and 2,000 libri rari in the Swift collection at the University of Münster.

Elsewhere, the library of the University of Münster owns a Swift collection. One of the university’s professors of English literature befriended the New Yorker Irvin Ehrenpreis, ‘the doyen of Swift-related research’. After Ehrenpreis’s death in 1985, his family encouraged Prof. Hermann J. Real to realise their shared plan to found a Swift research centre in Münster. Today the collection encompasses more than 10,000 bibliographic entities and 2,000 libri rari.

A graduate of Dublin City University, Laura Patz lives and works as a freelance journalist in Berlin.