Juno and the Paycock

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, General, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2011), Reviews, Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 19

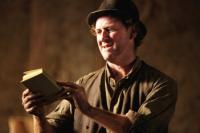

Joxer Daly—O’Casey’s play reflects a general disillusionment and alienation. Much of this is captured by the character of Captain Boyle and his appalling sidekick, Joxer, a brilliant comic duo played memorably by Ciaran Hinds and Risteard Cooper.

This is the 45th production of Juno and the Paycock at the Abbey, and this latest, directed by Howard Davies, is a joint venture with the National Theatre of Great Britain. It is appropriate that O’Casey should be the subject of such a collaboration given the circumstances of his own life. Although he made his reputation as a dramatist at the Abbey with his great trilogy of plays about the Irish revolution and civil war, The Plough and the Stars, Juno and the Paycock and The Shadow of a Gunman, between 1922 and 1926, O’Casey moved to London even before the riots that greeted the performance of the latter play and was based in England for the rest of his life. His love–hate relationship with Ireland is mirrored in the image of the Irish revolution and of Irish society that he created in the trilogy of plays which still largely define his dramatic legacy, despite the fact that he continued to write plays for another 35 years. The number of times that Juno has been put on at the Abbey is all the more remarkable given the fact that he refused to allow his plays to be performed there for some years until shortly before his death in 1964.

Juno and the Paycock was first performed at the Abbey in March 1924. The problem with such a classic play is to try to recapture something of the impact it must have had on the audience when it was first presented. The civil war, which dominates the play’s action, was still smouldering when it was first performed. But despite the play’s savage exposure of the inhumanity of war and the bankruptcy of both establishment and revolutionary varieties of nationalism, and the weakness of the only socialist male character, O’Casey continued to build on the success of his earlier The Plough and the Stars. The hostile reception of the third play in the trilogy, The Shadow of a Gunman, in 1926 was the result of an attack orchestrated by members of Cumann na mBan and Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, perhaps indicating a growing resistance to any non-heroic representation of the Easter Rising as well as the puritanical objections to the juxtaposition of patriotism and prostitution on the Irish stage. Republicans may also have been out to embarrass Yeats and the Abbey management for accepting support from Ernest Blythe and the government of the Irish Free State.

Juno Boyle (Sinéad Cusack)—Mrs Tancred’s words, ‘take away our hearts of stone and give us hearts of flesh’, are given added power when Juno repeats them at the play’s climax when her son is shot as a deserter by his former IRA comrades.

Although not a piece of dramatic realism, Juno and the Paycock, like O’Casey’s other plays of this period, departed from the conventions in representing the life of the Dublin slums and, in particular, the language of the slum-dwellers. The tenement room of the Boyle family is both realistic and a brilliant dramatic symbol of a broken country. The slum-dwellers are the impoverished inhabitants of the shell of faded grandeur. The crumbling plasterwork and majestic proportions of the set mock the poverty of their lives. O’Casey’s anger at the hollowness of a revolution that left the slum-dwellers in the same conditions as before was eloquently described in his semi-fictional autobiography, where he was scathing about the middle-class nationalists who had conducted the revolution. Behind the pathos and frustration of this image of the poor as victims of history lies a well-worn truth about the Irish revolution, that the real social revolution in Irish history had already taken place before 1916 and that it was an agrarian revolution engineered by the land acts. By 1922 the majority of the population had no wish to countenance a more radical social revolution, which might have changed the condition of labour or the urban poor, who remained marginalised in the new Ireland. On another level, however, the claustrophobic world of the tenement and the intrusion of violence and war are symbolic of the country as a whole in the civil war period. The Boyle family and their neighbours are victims of violence and madness but they stand for the whole war-weary people. O’Casey’s play reflects a general disillusionment and alienation. Much of this is captured by the character of Captain Boyle and his appalling sidekick, Joxer, a brilliant comic duo played memorably by Ciaran Hinds and Risteard Cooper. Boyle is work-shy and selfish, given to absurd levels of self-delusion. The prospect of a legacy transforms him into a strutting braggart with delusions of importance. He sheds his anti-clericalism with his old clothes and becomes a caricature of a man of property. Joxer, the quintessential hanger-on, is also an endless source of sham-patriotic clichés and mawkish Hibernicism. A.M. Sullivan’s Story of Ireland and Boucicault’s Colleen Bawn are elements of their maudlin repertoire. Rather like the independent country itself, the festivities are brought to an abrupt halt by the intrusion of violence, the shooting of a neighbour’s son by Free State troops and the moving speech of his mother, Mrs Tancred: ‘take away our hearts of stone and give us hearts of flesh’—perhaps some of the most famous lines in the Irish theatre, given added power when Juno repeats them at the play’s climax when her son is shot as a deserter by his former IRA comrades.

The play ends with Captain Boyle (Ciaran Hinds) drunk and alone, deserted even by Joxer, who steals his last sixpence, but the chink of light is provided by the courage of Juno, who leaves with her daughter and the latter’s unborn child to start a new life somewhere else.(All images: Mark Douet)

The themes of alienation and disillusion are universalised in the play by the fundamental humanity of the female characters, notably Juno herself. Even the idealistic socialist, Jerry Devine, turns out to be incapable of overcoming his conventional attitudes to Mary when she turns out to be pregnant. In the wake of the multiple blows inflicted by the loss of the legacy, the plight of her daughter and the tragedy of the killing of her son, Juno rejects the fatalism that such things are the will of God. They are the result of the stupidity of men. The play ends with Captain Boyle drunk and alone, deserted even by Joxer, who steals his last sixpence, but the chink of light is provided by the courage of Juno, who leaves with her daughter and the latter’s unborn child to start a new life somewhere else. HI