July 16

Published in On this Day listing-

- 1969 Dr James McCann resigned as archbishop of Armagh and primate of all Ireland. He was succeeded by Dr G. O. Simms. Fr Eamonn Casey, director of the Catholic Housing Aid Society in London, was appointed RC bishop of Kerry.

-

- 1968 An archaeological team discovered a passage and burial chamber at Knowth, Co. Meath.

-

- 1967 A passage and burial chamber were discovered beneath the tumulus at Knowth, Co. Meath, by a team of archaeologists led by Dr George Eogan.

-

- 1936

Above: George McMahon (born Jerome Bannigan) is led away by police after his botched assassination attempt on King Edward VIII on 16 July 1936.

George McMahon (36) achieved instant notoriety when he produced a revolver as King Edward VIII rode down Constitution Hill towards Buckingham Palace after reviewing troops in Hyde Park. The king, however, was unharmed. A special constable struck McMahon, sending the weapon skidding towards him and striking the hind leg of his horse. Born Jerome Bannigan in Ireland and raised in Glasgow, McMahon appeared in court in mid-September, where his claim that he was part of an international plot to shoot the king was rejected as fantasy. Found guilty of ‘producing a revolver near the person of the King with intent to alarm His Majesty’, he was sentenced to twelve months’ hard labour. Whether or not McMahon did intend to ‘remove’ the king, Edward’s position on the throne was by that stage under intense scrutiny by the British government. Arriving back from a two-month summer break, Prime Minister Baldwin found his in-tray full of complaints from expatriates about the king’s undignified behaviour during a summer trip in the Adriatic on a hired yacht with the dreadful, twice-divorced Mrs Simpson. Worse than that, it seemed that he was determined to marry her. Meanwhile, de Valera, unaware of Baldwin’s concerns, was busy drafting a new constitution for Saorstát Éireann which would have no place for Edward or his successors. Thus when Edward removed himself from the throne—he abdicated in December that year—Dev wasted no time in removing him from the existing constitution. Two days after the abdication, the Executive Authority (External Relations) Bill was passed, clearing the way for the constitution of 1937, a republican constitution in all but name.

- 1936

-

- 1936 Irishman George McMahon was disarmed by a policeman as he attempted to shoot King Edward VIII as the king rode down Constitution Hill in London. He was subsequently sentenced to twelve months’ hard labour for producing a revolver with intent to alarm His Majesty.

-

- 1923

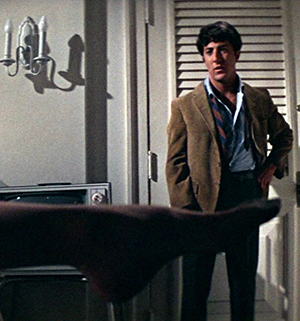

Above: The Graduate (1967) was drastically cut, including the crucial seduction scene between the Anne Bancroft and Dustin Hoffman characters.

The Censorship of Films Act—‘to protect the citizens of the State from any films considered to be indecent, obscene, or blasphemous … or subversive of public morality’—was passed by Dáil Éireann after a lively debate. Typical of the contributions was that of William Magennis TD, who told the House that the cinema was a place where ‘the loose views and the vile lowering of values that belong to other races’ were being forced upon us. The first censor, James Montgomery, famously stated that he knew nothing about films but knew the Ten Commandments and took them as his code. Over his seventeen years in office he banned over 1,500 films and cut many more. Of the British film Father O’Flynn (1935) he commented: ‘Reel one might be called stage Irish but the girl dancing on the village green shows more leg than I’ve seen on any village green in Ireland. Better amputate them.’ Until the Film Appeals Board (FAB) was set up in the 1960s, Ireland had one of the strictest regimes of film censorship in the world. No distinction was made between films for adults and children; all citizens were treated as children. Thus many of the great classics, including Gone with the Wind (1939), Brief Encounter (1945), Psycho (1960) and The Graduate (1967), were drastically cut, the latter with an X-certificate and eleven cuts, including the crucial seduction scene between the Anne Bancroft and Dustin Hoffman characters. Technological developments have long since overtaken the idea of film censorship. In 2008 the post of film censor was reclassified as ‘Director of Film Classification’.

- 1923

- 1877 Tom Crean, Antarctic explorer, born in Anascaul, Co. Kerry.

- 2018 A megalithic passage tomb dating back some 5,500 years was discovered at the eighteenth-century Dowth Hall, Co. Meath.