John Quincy Adams on the Origin of ‘Erin’s Wrongs’

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 1996), Volume 4

John Quincy Adams from an engraving by Asher Brown Durand, 1826(Courtesy of Collection of The New York Historical Society)

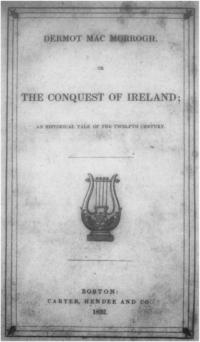

After his defeat in the 1828 presidential election John Quincy Adams was faced with a crisis of self-confidence which, in an unusual move for an ex-President of the United States, he met by re-entering political life as a congressman and by reconfirming his own moral and ethical stance as an Adams through the medium of poetic composition. His epic Dermot MacMorrogh or the Conquest of Ireland; an historical tale of the twelfth century, published in Boston in 1832, was written in this period of retrospection.

The poem is a lengthy mock-heroic epic of 266 stanzas and four cantos: ‘The Elopement’, ‘The Expulsion’, ‘The Restoration’ and ‘The Conquest’. In melodramatic and sometimes lurid detail, John Quincy Adams tells the story of the supposed abduction of Derbforgaill by Diarmait Mac Murchada and the consequences of the anti-hero’s actions which culminated in the Anglo-Norman conquest. Written in the ottava rima metre, the singular influence on Adams’s poetic style in this composition was Byron and particularly that poet’s Beppo, composed in 1817. As his diaries testify, Adams was no stranger to the muse of poetry. As a young man he had composed romantic verse and translated Wieland’s Oberon and ‘The Thirteenth Satire of Juvenal’ which were favourably received. In later years however, his poems, notably ‘The Wants of Man’ and ‘Justice’, became increasingly preoccupied with themes of society and religion.

‘The melancholy madness of poetry’

John Quincy Adams was born 11 July 1767 in Braintree, Massachusetts, eldest son of John and Abigail Adams. Virtually raised and educated to inherit the presidency, the principle achievement of his diplomatic career prior to his presidential term (1824-28) was the formulation of the Monroe Doctrine (1823) and in his post-presidential period he campaigned vigorously against the expansion of slavery. In the 1828 presidential election he was defeated by Andrew Jackson and in an atmosphere of some resignation returned to Quincy in 1829 and re-assembled his library. After a short retirement, in a unique departure for an ex-president, he ran

A representation of Diarmuit Murchada from the margins of a late edition of the account of Giraldis Cumbrensis.

for Congress in 1830, was elected as representative for the Plymouth district of Massachusetts, and served in the House until his death in the Speaker’s Room at the Capitol on 23 February 1848. It was during his short retirement that he composed Dermot MacMorrogh or the Conquest of Ireland as an ‘object of pursuit’. On 23 February 1831 he wrote in his diary:

One of these rhyming fits is now upon me…and in my morning walk form two to three stanzas of a tale I have undertaken, far beyond my depth, and which I shall certainly never get through. But so totally does it absorb my attention while engaged upon it, that in my morning walk around Capitol Square I go out and return almost without consciousness of the passage of time—the melancholy madness of poetry without the inspiration.

Despite his reservations about completing the poem, in a subsequent diary entry of 10 March, he admitted that he was now engrossed in the subject and speculated that it would run to 100 or more stanzas. Realising that he would have to equip himself with ‘a knowledge of Ireland, physical, moral, and political’, he applied himself to the necessary preparatory work with considerable zeal, drawing upon the historical works of Cambrensis, Hume, Leland and Lingard for the chronology of the events of the Anglo-Norman conquest and the historical detail of his characters. Although a printed version of an earlier thirteenth-century chanson or geste based on the Mac Murchada story—The Song of Dermot and the EarI—was available in Walter Harris’s Hibernica as early as 1747, Adams appears to have been unaware of its existence.

‘Eternal justice’

Quincy Adams’s epic is didactic, polemical and satirical. It is a plea to young American citizens to embrace the true republican value of moral excellence. It is also dedicated to voicing the plight of the Irish and a recent reading of the poem by Jacqueline Kaye suggests that it may be conceived as anti-Jackson. For Quincy Adams history was the school of morals and, as the pursuit of moral excellence was deemed by him the essence of republicanism, the entire thrust of his poem was to be a lesson in good citizenship. A wholesome and just society could only be created and sustained by upholding the virtues of conjugal fidelity, genuine piety and devotion to country. For him, the anti-hero Mac Murchada represented the very antithesis of these virtues, his name being synonymous with adultery, impiety and treachery.

But Dermot’s heart in quite

another mould

Was form’d—faith, virtue,

were to him unknown:

Brave was he as Ororik [Ó Ruairc], and as bold;

But truth and justice never

reach’d his throne

The fiercest passions still

his breast control’d,

Reckless of feelings other

than his own—

His word, his bond, his oath,

nay altogether,

Weigh’d in his balance, lighter

than a feather.

As Quincy Adams had no ostensible interest in Irish affairs he would, at first glance, appear an unlikely candidate for the composition of an impassioned epic espousing the cause of Ireland. There is no evidence to suggest that he had any involvement with Irish political agitators and he did not apparently cross the Irish Sea during his period as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Great Britain 1815-17. Ultimately it was his quest for ‘eternal justice’ and his support for the rights of the oppressed in general which led him instinctively to Ireland and the Irish. In the purposeful and wide-ranging reading which consumed much of his leisure hours, the story of Diarmait attracted him as a subject upon which he could exercise his compulsion to create and teach. As a writer, the obscurity of the subject of this compelling story worked in his favour as it had fresh appeal for the American public. The historical import of Mac Murchada and the conquest would already have been known to him through his father’s exploration of the constitutional relationship between England and Ireland. In his paper ‘To the inhabitants of the Colony of Massachusetts-Bay’ (3 April 1775) John Adams stressed that unlike any colony in America, the authority of the English parliament, if it had any, to bind Ireland, was based upon the consent of the Irish to be so governed as stated in Poynings Law and that this situation had been brought about by the conquest.

For Quincy Adams the origins of ‘Erin’s wrongs’ lay in its conquest by Henry II aided and abetted by the ‘unprincipled ambition’ of Diarmait Mac Murchada—’a transaction…of melancholy depravity’—which could not have been accomplished ‘but by a complication of the most odious crimes, public and private’. Motivated by the belief that the conquest of Ireland ‘had sunk into a mere incident in the annals of England, scarcely known or noticed by the general readers of history’ he sought through the medium of his epic poem to relate Ireland’s plight and to encourage her to stand ‘an independent State amidst her peers’.

Treachery and adultery

Treachery and adultery

The tone of the poem is dominated by themes of betrayal at different levels but the ultimate betrayal is seen as the centuries of oppression to which Ireland was subjected through Mac Murchada’s treachery. As a child of the American Revolution, Quincy Adams’s love of country had a strong intellectual basis as well as the passion of patriotism but this did not preclude suspicions among political opponents that the Adamses were pro-British. His own view of himself when returning to serve his country as a congressman was that this relatively humble office would confer ‘peculiar lustre upon his character as an American patriot and republican citizen’. As a fervent patriot betrayal of country was anathema to him and significantly he draws a parallel in the poem between Mac Murchada’s treason and that of his near contemporary Benedict Arnold (1741-1801 ) the American Revolutionary War general.

Thus was the shame of servitude her lot:

And has been since. from

that detested day,

When Dermot all his country’s claims forgot;

And basely barter’d all

her rights away.

Oh! could the muse be heard,

his name should rot

In fresh, immortal, unconsum’d decay—

And be, with Arnold’s name

transmitted down,

First in the roll of

infamous renown.

Another form of betrayal explored in the poem is that of marital infidelity. In the first canto entitled ‘The Elopement’ he focuses in particular on the character of Derbforgaill, wife of Tigernán Ó Ruairc, king of Breifne. Mac Murchada’s taking of the ill-fated Derbforgaill in 1152 has been the subject of much debate, some believing that she was abducted to satisfy his ‘insatiable, carnal and adulterous lust’, others suggesting that she was a willing accomplice. Adams is resolute that she was ‘false to her husband, traitress to his bed’ and that ‘for two long years she spun the base intrigue’. His condemnation of her however is apologetic, and lest he be accused of misogyny, in a long digression he explains to his female readers that his story of this ‘faithless bride’ is not intended to shame womankind but to ‘shew one sinning woman for example’. The adultery of Mac Murchada and Derbforgaill propels the action which culminates in the Anglo-Norman conquest. Likewise Henry II is cast as an adulterer with the ensuing chaos, private and public, which this brought—’his wife, his sons conspir’d against his head;…the direst ills the human heart can know, from wedlock’s broken bonds, forever flow’. Contemporary reviews of the poem inferred that these twelfth-century adulterers had contemporary and real-life counterparts in the form of Quincy Adams’s political opponents. As the American Monthly Review February 1833 pointed out ‘the newspaper stories about Mrs Jackson and Mrs Eaton seem to have supplied the character for Dovergilda’. These scandals derived from the inadvertent bigamous marriage of Mrs Jackson and the mysterious disappearance of the first husband of Peggy Eaton, who subsequently married President Jackson’s Secretary of War. Here again was an example for Adams of how free-thinking and irreligion led directly to loose morals. Within his own family the disastrous consequences of lax morals led to the suicide of his son George after a short life of degeneracy and profligacy.

Largely disregarded by literary critics, the first edition of Dermot MacMorrogh enjoyed considerable popular success.

Popular acclaim

There were mixed reactions to Adams’s epic on its publication in Boston in 1832. It had tremendous popular sales and critical reviews ranged from the kind to the abrasive. Adams had no illusions about his poetic ability, nonetheless he believed that the compilation of poetry was not ‘unworthy of minds of the highest order, even if their poetry be not itself of much merit’. He had hoped that ‘a momentary curiosity would be excited by the name of the author, and the singularity of the subject’ and he had anticipated correctly as the first two editions of a thousand copies each sold out within the first year and a third edition was published in 1834. Writing to his publisher Melvin Lord on 3 December 1832 he feared that the literary batteries of the American reviews and possibly those from London and Edinburgh would come in the form of ‘red hot balls’. His fears were realised when the New England Magazine of December 1832 described his epic as ‘stale, flat and unprofitable without one single gleam of genuine poetry’. But the Christian Examiner and General Review (1833) wrote sympathetically ‘it is an error of the head, or of the press, but not of the heart’. However, his private letters indicate that he received public testimonials in abundance and as the sales figures confirm Dermot MacMorrogh was a popular success. It appears not to have been reviewed on the other side of the Atlantic and indeed it seems that it never reached Ireland, as a note in the Irish Book Lover of February 1951 established that there was no copy of the poem to be had in any Irish public or university library and that none of the Irish literary reviews of the period had taken notice of its publication.

As poetry, John Quincy Adams’s historical tale of twelfth-century Ireland does not always succeed, but its integrity, wit, scholarship and passion propel it along and engages the reader. Best read aloud, it will in Adams’s words ‘amuse some winter evening’. It is more successful in its intended purpose as a didactic and polemical exercise in which his deep sense of moral virtue and justice are given free rein.

Teach not your children then

to shun ambition:

Nor quench the flame, that must forever burn:

But, in the days of infancy,

their vision

To deeds of virtue and

of glory turn:

0f man, their mortal brother,

the condition

To mend, improve, and

elevate, to learn:

Then, all the means they

ever shall employ,

Will point to endless bliss,

and boundless joy.

Elizabeth FitzPatrick is an archaeologist at present conducting doctoral research at the Department of Medieval History, Trinity College, Dublin. Olivia Hamilton is a history graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, a writer and freelance editor.

Further reading:

C.F. Adams (ed.), Memoirs of John Quincy Adams comprising portions of his diaries from 1795 to 1848, vols. viii and ix (1874-7, reprint New York 1970).

J. Kaye, ‘John Quincy Adams and the Conquest of Ireland’ in Éire-Ireland, vol. 16, No. 1, 1981.

P.C. Nagle, Dissent from glory, four generations of the John Adams family (New York/Oxford 1983).