John Boyle O’Reilly & Moondyne (1878)

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 1 (Spring 2002), Volume 10

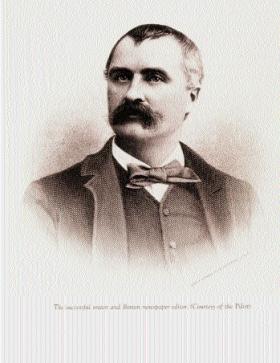

John Boyle O’Reilly, 1844-1890. (The Pilot)

Arrested for treason against the British Crown and deported to the penal colonies of Australia, the Irish revolutionary John Boyle O’Reilly managed to escape to the United States and within a few years became one of Boston’s most prominent political and literary figures, one of the best known Irish immigrants in the United States, and one of the most charismatic individuals of the late nineteenth century. He wrote some of the most popular poetry of the period as well as one obscure but swashbuckling novel, Moondyne (1878), based in part upon the spectacular events of his own life.

O’Reilly was a hero of national and international stature. His reputation, however, rested on more than his personal charisma, staggering life history and notorious achievements as political activist and editor of The Pilot, the most influential Catholic newspaper of the nineteenth century. His clout truly stemmed from the way in which other Americans saw him as embodying a cultural role of conciliator, communicator, and cross-cultural ambassador. Both O’Reilly’s contemporaries and more recent scholars have hailed him as the great go-between for Brahmin Boston and what was rapidly becoming a city of Irish Catholic immigrants. By situating Moondyne in the context of not just the Australian penal system, nor even the Irish Land question, but in the context of questioning how America itself might be a model for how cultures could work together, Moondyne explores ideas the shouldn’t be overshadowed by its swashbuckling tone. Moondyne takes on the question of prison justice, yes. And it certainly poses questions about the United States. But it also asks its readers how we might imagine models for co-operation among seemingly irreconcilable enemies.

Moondyne’s plot

The central figure of the tale is the convict called ‘Moondyne’—a name given him by his Aborigine friends in the Australian outback. A victim of a heartless British system of capitalism and cruelty, our hero was arrested when caught poaching deer in order to feed his starving family. Summarily transported to the convict colonies, he manages to escape with the help of Aborigines and share with him the secret of an immense gold mine.

Returning to England under an assumed name, the convict, now known as Wyville, begins life anew. As a mysterious man of wealth and respected humanitarian with special expertise on theories of land distribution, legal codes, and penal reform he befriends a young man, William Sheridan. In the course of his charities Wyville becomes involved with several sub plots; among other projects, he takes up the cause of a young woman, Alice, who is falsely accused of murdering her own child. Hapless Alice is transported to Australia and she, Wyville/Moondyne, Sheridan, and a dozen other characters all end up on the same convict ship bound for Freemantle. Ostensibly returning to Australia upon the request of the British government in order to reform the land policies and penal system out there, Wyville/ Moondyne nonetheless manages to save Alice from both despair and false imprisonment, re-unite a pair of lovers, punish the wicked, and make numerous suggestions for how land should be distributed in a just society, all before he dies in an attempt to save a villain from certain death in a raging brush fire.

There’s melodrama to be sure and troubling themes of race and nation that complicate much of the novel’s impassioned goals. And yet, for all of its exotic setting and themes, the sense that kindness is ultimately more important than nationalism, and that charity to the least deserving is the only charity worth valuing, allows Moondyne to be a novel of singular beauty and moral significance.

O’Reilly’s many lives

O’Reilly’s many lives

The story of O’Reilly’s life is spectacular on its own merits and deserves retelling, but the events and themes in Moondyne closely parallel his own life, and are a reminder that the melodrama he might easily be accused of was often very true to his own experience.

John Boyle O’Reilly was born on 28 June 1844, in County Meath, the son of a schoolteacher William David O’Reilly and orphanage matron, Eliza Boyle O’Reilly. Growing up during the Great Famine of the 1840s, O’Reilly was fortunate to have parents steadily employed with the government rather than dependent upon the potato crop. And so he survived the famine and was educated in his father’s school until the age of eleven when, after his brother fell ill with tuberculosis, O’Reilly took over his brother’s apprenticeship at the Drogheda Argus, a local newspaper. After a couple of years there, O’Reilly went to live with relatives in England, who set him up with a job at another local paper.

Joins the Fenians

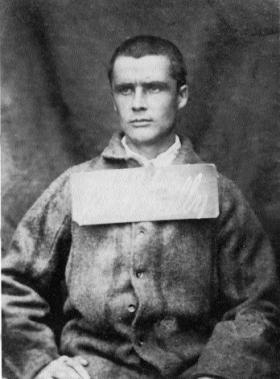

In 1863, O’Reilly returned to Ireland and enlisted with the British army’s 10th Hussars then stationed in Dublin. Within one or two years he was approached by representatives of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and, in perhaps the most momentous decision of his life, he took the Fenian oath and became part a scheme to infiltrate the British army in Ireland: he reportedly recruited over eighty other Irishmen to the cause. Informers betrayed the Fenians and in 1866 the authorities began a series of raids and arrests, taking O’Reilly in March of 1866. As an Irish political offender but also as one of seventeen military offenders arrested, O’Reilly’s treason was considered especially heinous and at his court-martial he was initially sentenced to death. However, on the grounds of his youth (he was only twenty-one at the time of his arrest), his sentence was commuted to twenty years at hard labour. In July 1866 he used a nail to carve onto his cell walls the words: ‘Once an English soldier; now an Irish Felon; and proud of the exchange’. He was to need such bravado, for his hardships had only just begun.

Moved from prison to prison, O’Reilly reportedly tried to escape from Chatham, Portsmouth, and Dartmoor prisons, although no official documents record such attempts. As a young man with a long sentence ahead of him and working under cruel conditions, he probably thought he had little to lose. Ironically, his reputation as an escape risk may have been what persuaded officials to send O’Reilly abroad: many of other military Fenians languished in British prisons for years. Whatever the reasoning behind his selection, O’Reilly and sixty-one other Fenian prisoners were sent to Fremantle, Western Australia, arriving there on 9 January 1868.

When he arrived in Fremantle, a settlement on the mouth of Swan’s River, his skills were quickly put to use in the comparatively free prison system of that time. He served briefly as an aide to the parish priest and then as supervisor of a small lending library. These attractive duties were altered when, after only a short time, he was sent out to join a Bunbury road crew. His education again served him well and he was given various clerk and messenger jobs with the road crew which allowed him considerable freedom. It was at this point that O’Reilly even developed a friendship with one of his supervisors, warder Henry Woodman. Woodman introduced O’Reilly to his family and the young and charismatic, O’Reilly attracted the affections of the warder’s daughter, Jesse. Although this romance seems incredible, journals and testimonials vouch that some sort of affair did indeed occur and it is tempting to read the romantic scenes in Moondyne between Will Sheridan and Alice Walmsley as shaped by O’Reilly’s memories of a hopeless love affair. Nothing could come of such a real life liaison, however, and O’Reilly’s life instead took another dramatic twist.

John Boyle O’Reilly in Mountjoy Gaol, 1866. (Larcom Collection, New York Public Library)

Escape from Fremantle

Assisted by a local priest, Father Patrick McCabe, and a settler named James McGuire, O’Reilly arranged to be smuggled away on an American whaling ship. The plans didn’t work out as they were supposed to. O’Reilly ran off from his work crew on 18 February 1869 and was met by McGuire and friends who led him to the coast. Hidden in the sand dunes, O’Reilly spent horrible days suffering from the elements and waiting to be picked up. He saw the ship, the Vigilant, which was supposed to take him on, but the captain did not see the small boat O’Reilly was on and so passed him by. Father McCabe and Maguire frantically made other arrangements and found another American whaler, the Gazelle, which agreed to take O’Reilly aboard.

Before O’Reilly could be smuggled aboard, however, McGuire’s mysterious errands in the bush came to the attention of ticket-of-leave prisoner (essentially a paroled convict), Thomas Henderson, alias ‘Martin Bowman’, a man sent to Australia after being sentenced for attempted murder. Bowman was quick to seize the opportunity to blackmail McGuire and O’Reilly, forcing them to smuggle Bowman aboard the Gazelle as well. This time the rendezvous was successful and both Bowman and O’Reilly made it on board. For several months they sailed on the Gazelle and O’Reilly became friends with both the captain, David Gifford, and the third mate, Henry C. Hathaway. When the boat stopped at the British island of Rodrigues, government authorities insisted on inspecting it for fugitives and stowaways, especially the notorious escapee John Boyle O’Reilly. One of the regular seamen pointed at the hated Martin Bowman, who was immediately led away in chains. Hathaway and O’Reilly feared that as soon as he was in a position to bargain, Bowman would give away O’Reilly and so they schemed a fake suicide. The next day, when the authorities returned to the boat they were greeted by such genuine sorrow on the part of the crew (who believed O’Reilly really had killed himself by jumping overboard rather than be taken back to Australia) that they left convinced. O’Reilly may have forgiven Bowman’s treachery but he never forgot it. In Moondyne, the double-dealing Sergeant who reneges on his deal and murders the aboriginal guardians of the mine, is aptly named Isaac Bowman.

Arrives in America

This experience at Rodrigues was a terribly close call. And so, when at sea the Gazelle sighted a whaler out of Boston, the Sapphire, O’Reilly look leave of the Gazelle and travelled to Liverpool with the Sapphire as a working sailor. Nervous about staying too long in England, within a couple of days O’Reilly arranged to be taken aboard the Bombay, a ship leaving Liverpool for Philadelphia. Finally on 23 November 1869 O’Reilly arrived in the United States. He stayed briefly in Philadelphia and New York with ecstatic and welcoming members of the Irish immigrant community, until January 1870 when he moved up to Boston—the city with which he was associated for the rest of his life.

Within a couple of months he established himself as a reporter for The Pilot, then an eight-page weekly newspaper covering Irish and Irish-American affairs. He quickly made a name for himself, covering events such as the disastrous 1870 Fenian invasion of Canada and bloody Orange riots in New York between Catholic and Protestant Irish immigrants in 1870 and ‘71. His balanced and critical assessment of such events did much to mitigate his revolutionary past. In a Pilot editorial of 1870 he wrote: ‘Why must we carry wherever we go those accursed and contemptible island feuds? Shall we never be shamed into the knowledge of the brazen imprudence of allowing our national hatreds to disturb the peace and safety of respectable citizens of this country?’ O’Reilly’s increasing conservatism was skilfully parcelled out. As a rising celebrity, he had the clout to break the unified front that had often characterised the public discourse of Irish America without alienating his many followers.

O’Reilly was rapidly promoted at The Pilot and soon felt established enough to wed Mary Murphy, a daughter of Irish immigrants. By 1876 he had become part owner and editor-in-chief of The Pilot. From then until his death in 1890, O’Reilly controlled what was probably the second most powerful media outlet in Massachusetts short of the Boston Globe. He wrote editorials, hired writers, and built The Pilot up from being a minor Catholic news weekly, to being a major newspaper with an international reputation. Elected president of the Boston Press Club in 1879, O’Reilly’s status assured that the ‘ethnic’ papers in Massachusetts would get a serious hearing.

Despite a rather complex position on the issue of racial equality (he believed that enfranchisement of Blacks had been a mistake) O’Reilly was hailed by many of his contemporaries and by more recent scholars as a champion of ‘a spirit of equality’ which continually allied the cause of Ireland with the suffering of the ex-slaves in the United States. Taking on the mantle of the great liberators with whom he associated—Wendell Phillips, William Emery Channing and Charles Sumner—O’Reilly used his newspaper to preach brotherhood across religious and racial divides. As O’Reilly announced in one of his editorials, The Pilot was to be the voice of all who ‘yearned to be free’ no matter what their ‘race, colour, creed, or former condition of servitude’.

The Gazelle, the whaler which rescued O’Reilly in 1869.

Boxed John L. Sullivan

If his credentials as newspaperman and an Irish revolutionary weren’t enough to give him status in the Irish-American community, O’Reilly built up for himself a colourful and manly social reputation. He endeared himself to the sports enthusiasts by boxing with John L. Sullivan and he regularly participated in public sporting events. And despite his increasingly moderate and assimilationist politics, he never forgot the men he had left behind. In 1876 he helped engineer the daring rescue of five Fenian prisoners held in Western Australia, an event that received considerable press coverage and popular accolades.

O’Reilly’s ascent through Boston society was truly spectacular. Within a short number of years he was not only considered the great spokesman for the Irish immigrants of Boston, but also as a well known poet, public speaker, sportsman, and activist for political causes ranging from labour reform to civil rights. He counted among his good friends not only the stalwarts of what was rapidly becoming an Irish political machine, but also literati such as Oliver Wendell Holmes and Julia Ward Howe and activists such as Wendell Phillips. He became friends with President Grover Cleveland and with Cardinal Gibbons, the head of the Catholic Church in America. O’Reilly was president of both the literary Papyrus Club and the Boston Press Club. A member of numerous Catholic charities and radical reform movements, O’Reilly was one of the best known men of Boston. Bridging the gap between the Brahmin world of Beacon Hill and what was rapidly becoming a city dominated by Irish-American immigrants, O’Reilly was hailed as the great cross-cultural ambassador.

Freemantle prison, where O’Reilly was held, c.1860. (Battye Library)

Informal ambassador

Although his celebrity status was based upon his politics as much as his exploits, what allowed him to truly serve as an informal ambassador for the vast underclass of working Irish-American families in Boston, was his literary work. He had begun writing poetry as a child and continued during his long stints in prison and aboard ships. With The Pilot as a ready outlet, O’Reilly was soon waxing poetic with great regularity. His speciality was uplifting verse which, in simple couplets, would call out for freedom and against tyranny. These immensely popular poems, written in a romantic and sentimental tradition promoted a genteel bourgeois sensibility. Nostalgic, often didactic, and essentially proselytising, these poems appealed to the Irish immigrants who sought assimilation and also to the ‘proper Bostonians’ who could read O’Reilly’s verses and see that while all was not well in the world, causes were common and values were shared. Through works such as his most famous poem, ‘In Bohemia’ (1888), O’Reilly attracted audiences from all sides. He had a fervent belief in the arts themselves as bridging the gap between the powerful and the powerless and his easy radicalism cannot be dismissed simply because it was reprinted on Christmas calendars and recited in Boston drawing rooms.

O’Reilly’s poetry attracted important commissions and throughout the 1870s and ‘80s he wrote hundreds of ‘occasional’ poetry to mark significant events. Some of his most important poems include ones written about the African-American patriot Crispus Attucks, whaling adventures, the American Civil War, Western Australia, and of course, Irish freedom. His poetry was so frequently anthologised and quoted that, after his death Harper’s Weekly magazine claimed:

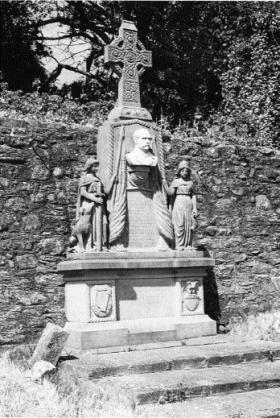

The John Boyle O’Reilly monument, erected in 1903, at Dowth, County Meath. (A.G. Evans)

[He was] easily the most distinguished Irishman in America. He was one of the country’s foremost poets, one of its most influential journalists, an orator of unusual power, and he was endowed with such a gift of friendship as few men are blessed with.

Thanks to his charisma and mentorship, a coterie of genteel Catholic writers developed around The Pilot of the period, a circle including poets such as Louise Imogen Guiney. But O’Reilly’s poetry was part of a broader world and in 1889, O’Reilly’s commission to write the dedicatory poem for the Pilgrim monument at Plymouth Rock should be seen as one of the most extraordinary moments in American literary history. This foreign-born poet was selected over various Brahmin luminaries to mark the most American of icons. Along with Emma Lazarus’s poem, ‘The New Colossus’ (1883), placed on the Statue of Liberty, O’Reilly’s symbolic ascendancy to the heights of cultural acclaim marked a moment in which the resolutely complex nature of American national identity was proudly highlighted in the most public of forums.

O’Reilly died suddenly in 1890 as a result of an accidental overdose of his wife’s sleeping medicine. He had suffered terribly from exhaustion and insomnia for the months before his death and many scholars have seen his death as the result of the tremendous tensions he was under to constantly appease, explain, and negotiate among various groups. Whatever the cause, his sudden death at a comparatively young age—leaving a wife and four daughters—shocked Boston and the world. Tributes poured in from presidents and poets. Memorial services were held in cities and townships around the world. The New York Metropolitan Opera House was filled to capacity for a civic ceremony of remembrance. Reading groups and social clubs were founded in O’Reilly’s name, scholarships were endowed, statues put up, and honorary poems were written. Friends throughout Ireland, Australia, and the United States mourned together.

Legacy

John Boyle O’Reilly certainly left a literary legacy—his poems, his newspaper editorials and, of course, Moondyne. His crusade to actively change the social world around him may have led him to create poetry often criticised as didactic or sentimental and Moondyne arises from the same crusading impulse, to be sure. Nonetheless, Moondyne was written at a time when sentiment and inspiration were understood as effective means of motivating genuine political change. A fiercely anti-imperial novel which nonetheless presents degrading portraits of Aborigines and glowing praise for capitalist exploitation of the British empire, the contradictions of this work manifest deep cultural anxieties over the ethical imagination. For a novel concerned with re-humanising prisoners, a truly miserable underclass of humanity, it still has trouble conceiving of humanity in its most inclusive sense. Yet, Moondyne offers us views on class, race, nation, and justice that defy easy categorisation. A disquieting adventure, it employs stock characters and ridiculous coincidences to frame issues that are anything but stock or ridiculous. And while Moondyne himself may not seem as heroic or believable today as he might have seemed in the nineteenth century, the courageous breadth of this novel speaks to us more powerfully than ever. Scorning pity and scoffing at hypocrisy, O’Reilly believed in redemption for people that society would far prefer to forget.

Susanna Ashton lectures in English at Clemson University, South Carolina.

Further reading:

A. G. Evans, Fanatic Heart: a life of John Boyle O’Reilly 1844-1890 (Boston 1999).

J. Boyle O’Reilly, Moondyne: a study from the Underworld (New York 1879).