January 21

Published in On this Day listing- 1981 Sir Norman Stronge (86), former speaker of the Stormont parliament, and his son James (48), a member of the RUC reserve, were shot dead by the IRA at their home, Tynan Abbey, close to the Armagh/Monaghan border.

- 1981 Sir Norman Stronge, former speaker of the Stormont parliament, and his son James were shot dead by the Provisional IRA at their home, Tynan Abbey, close to the Armagh/Monaghan border.

- 1933 George Moore (80), author, notably of Esther Waters (1894), and leading light in the Irish Literary Revival, died.

- 1924 Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (53), communist revolutionary and premier of the Soviet Union since 1922, died of a stroke.

- 1922 The Craig–Collins agreement promised an end to the ‘Belfast Boycott’—the ban on northern goods coming into the South—in return for Catholics intimidated out of the Belfast shipyards being allowed to return.

- 1919 The first Dáil Éireann convened at the Mansion House, Dublin.

-

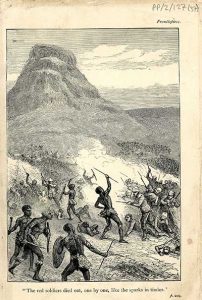

Above: Scene from the Battle of Isandlwana, 22 January 1879, the British Army’s heaviest military defeat by the Zulus. (Maynooth University Library)

1879(Jan.21–23)The Battle of Isandlwana/Rorke’s Drift. For many, the six-month Zulu War, prompted by the invasion of King Cetshwayo’s independent kingdom by British colonial forces under Lord Chelmsford, is viewed through the prism of the 1964 movie Zulu, which portrayed, with considerable artistic licence, the epic defence of a mission station—named after Irishman James Rorke, who had a trading store there— by c. 100 British troops (including a dozen or so Irishmen) against c. 3,000 Zulus. Thanks to Chelmsford, this strategically insignificant engagement was widely publicised. The bravery and self-sacrifice of the plucky Brits was applauded—no mention was made, of course, of their execution of c. 500 Zulu prisoners—and no less than eleven VCs were awarded (in contrast with one VC each for the 1944 D-Day landings and the entire Battle of Britain). All of this was designed by Chelmsford to distract British public attention from what had preceded it: the crushing defeat of his army at Isandlwana, with the loss of over 1,300 of his men, including many Irishmen, by the main c. 20,000-strong Zulu army, armed with spears and shields. While British gallantry was duly extolled (such as the heroic last stand of County Leitrim’s Col. Anthony Durnford and the valiant but fatal effort by Dubliner Lt. Nevill Coghill to retrieve his regiment’s colours), her historians are still trying to explain the defeat. Causes include the lack of screwdrivers to loosen the screws on the ammunition boxes. From a Zulu perspective, Isandlwana was a glorious victory—but a pyrrhic one. Cetshwayo knew that the British would regroup and re-invade, which they did. Superior numbers and technology prevailed, and by July, after six more battles, Zululand was entirely subjugated.

- 1924 Vladimir Lenin (53), Russian revolutionary, died.