James Murray—a life less ordinary

Published in Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2020), Volume 28Recovering a small piece of Dublin history with the return of a decorated Great War veteran’s medal.

By John Murray

Above: James Murray in Royal Dublin Fusiliers uniform during the Boer War. (Murray family)

On Wednesday 21 April 1909, James Murray, a labourer living in 8 Grant’s Row in central Dublin, left for work. It would prove to be a day of unimaginable tragedy for him. He left his young son James (4½ years old) in the care of his mother Jane, a widow who had moved in shortly before the previous Christmas to help look after her grandson. That morning Jane slipped out to run an errand, leaving young James momentarily unattended in their tenement room. She expected to be gone no more than five minutes and had just reached the front door. Elizabeth Murphy, a neighbour in the same building, heard the child screaming and ran into the room to find him in flames, from accidental contact with the open fire. Elizabeth immediately tore the burning garments off the boy, wrapped him in a blanket and carried him to the nearby Sir Patrick Dun’s Hospital. Young James died the following day owing to shock from extensive burns to his face and body.

His father and grandmother would subsequently be amongst the very first in Dublin to face prosecution under the terms of the newly adopted 1908 Children’s Act. This important piece of legislation had been introduced to protect vulnerable children, particularly from poorer backgrounds, from neglect and abuse. In essence it recognised for the first time the basic human rights of children. The case was heard in the Southern Divisional Police Court two weeks later on Wednesday 5 May. The presiding judge, Mr Drury, discharged James, completely absolving him of any responsibility for his son’s death. He fined Jane ten shillings and remarked that, as this was the first case he had had to deal with under the new act, he would let her off leniently.

Boer War service

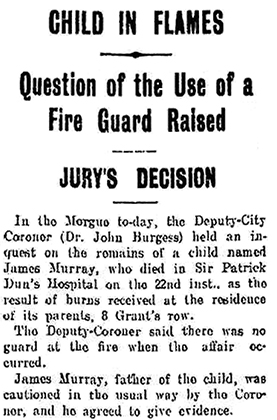

Above: Details of the inquest into James Murray Jr’s death, carried on the front page of the Saturday Herald on 24 April 1909. (Irish Newspaper Archive)

James Murray (senior) was born into a humble background around 1875 in the Donnybrook area of Dublin. He enrolled in the militia (the reserve forces) of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in March 1894 before joining the regiment on a full-time basis the following January, signing up with the regular army for a standard period of seven years with the colours, followed by five with the reserves.

James served as a private with the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers during the Second Boer War in South Africa (1899–1902). He was wounded in the opening salvo of that conflict, the Battle of Talana, on 20 October 1899. Tactically this event was considered a victory for the British, but it came at a very heavy cost in terms of casualties. It was also significant in that it marked the first hostile engagement for the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers since its creation in 1881, following the reorganisation of the British Army by the Childers reforms.

James recovered from his wounds and continued to serve in South Africa until the end of the war in 1902. He took part in several major operations, including the Battle of Tugela Heights and the relief of Ladysmith. In November 1902 James transferred to the army reserves and returned to civilian life in Dublin. He married his first wife, Mary Staunton, in Westland Row church in July 1904. When their first son, James, was born later that year, the family were living in Turner’s Cottages in Ballsbridge, a slum in the heart of affluent south Dublin. Their daughter Mary arrived in March 1907, but she died of pneumonia in June 1908. By now the family had moved to Asylum Yard, off Townsend Street, one of the most dilapidated and deprived slums in Dublin. The following month James’s wife Mary died. The subsequent tragic loss of his young son in April 1909 would thus mark the end of James’s entire first family.

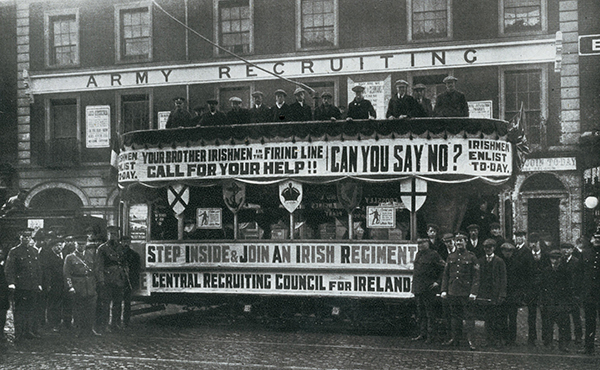

Above: Recruitment drive outside the British Army recruiting office at 23–25 Great Brunswick Street, now the Trinity Capital Hotel, Pearse Street. James Murray re-enlisted in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers on 29 March 1916, a month before the Easter Rising. (South Dublin Libraries)

First World War

James married his second wife, Jane Byrne, at Haddington Road church in May 1912. In the tumultuous years that followed, the hardships endured by the working classes during the 1913 Lockout in Dublin would be followed by the outbreak of the Great War in the summer of 1914, a global conflict that would leave an indelible mark on many Irish families.

On 29 March 1916 James Murray re-enlisted as a private with the 8th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, just under a month before the Easter Rising. His motivation for rejoining his old regiment remains unclear; it may have been out of a sense of duty and loyalty to former comrades or to secure a guaranteed income to support his young family, which by the end of 1916 had grown to include three small children under the age of four.

The 8th Royal Dublin Fusiliers formed part of the larger 16th Irish Division, which played a prominent role in the Battle of Messines in Flanders in 1917. This British offensive began at 3.10am on the morning of 7 June with the detonation of several enormous mines beneath German front lines. The mine blasts were heard in London and were considered the loudest man-made sound in history until the advent of the atomic bomb. Later that same morning the 8th Royal Dublin Fusiliers entered the field of battle and advanced towards their final objective. The British attack had been meticulously planned and was a notable success. It resulted in the liberation of the Belgian villages of Wytschaete and Messines and it also saw the men of the 16th Irish and 36th Ulster divisions (broadly representing the nationalist and unionist communities in Ireland respectively) co-operate and fight side by side.

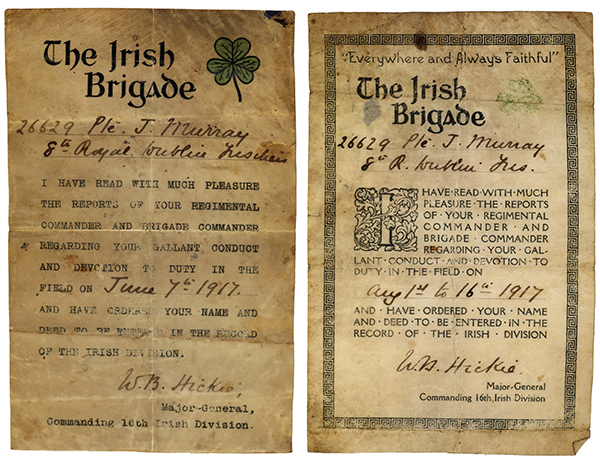

Private James Murray received a personal commendation (informally termed a ‘Hickie’s parchment’) from Major-General William Hickie, commander of the 16th Irish Division, for bravery and gallant conduct on that momentous day. He subsequently received a second Hickie’s parchment for bravery later that summer during the Passchendaele offensive (or Third Battle of Ypres). Both sides of the conflict suffered devastating losses during this period, with men, horses and tanks quickly becoming hopelessly mired in deep, thick mud. There was little shelter from the rain, which fell incessantly in the early part of August 1917. Owing to a complete lack of drainage, the rainwater filled up the numerous shell craters that scarred the landscape and drowned many men, particularly those who were too weak from their wounds to crawl out and escape. One noted historian described Passchendaele as the most harrowing ‘victory’ in British military history.

Above: ‘Hickie’s parchments’ (signed by Major-Gen. W.B. Hickie, commander of the 16th Irish Division) awarded to Private James Murray for bravery at the Battle of Messines Ridge in June 1917 (left) and during the Passchendaele offensive two months later (right). (Murray family)

Fenian Street tenement collapse

Above: The devastation following the 1963 Fenian Street tenement collapse. (Irish Photo Archive)

On 2 October 1917 Private James Murray was awarded the Military Medal for gallantry and devotion to duty under fire in battle. Two weeks later he was transferred to the Army Labour Corps, possibly because he was deemed no longer physically fit for front-line service. Following demobilisation after the end of the Great War, James returned to an Ireland undergoing considerable political and social upheaval. His growing young family moved to Upper Erne Street. Around 1945 James and his wife Jane moved into nearby 3 Fenian Street.

James Murray died on 13 April 1949 in St Kevin’s (now St James’s) Hospital, Dublin. Jane survived her husband by some 28 years and continued to live at the same address on Fenian Street until tragedy struck on 12 June 1963. The dilapidated three-storey tenement in which she was living catastrophically collapsed, along with the building next door, killing two young local girls who happened to be playing together in the vicinity. Ten days previously a decaying tenement on Bolton Street had also collapsed, killing two and trapping seven. These building collapses sent shock waves through Dublin, with the realisation that many similar old and neglected tenement houses could share a similar fate. The public enquiry that followed revealed the shocking scale of the housing problem, and Dublin Corporation was eventually compelled to speed up its programme for the planned relocation of tenement-dwellers to newly developing suburban satellite villages. As the inner-city tenements were cleared in the years that followed, the geography and social fabric of Dublin City was changed forever.

Jane Murray lost many of her possessions when her home on Fenian Street collapsed—they were literally swallowed in the rubble of that disaster. With the help of the Dublin branch of the British Legion, she made contact with the War Office Records Centre in Middlesex to request a copy of her late husband’s army records. This may have been to help account for lost military decorations or to facilitate a claim for pension entitlement. The letter of response received (dated 5 February 1964) is the only known surviving document that provides a complete summary of James Murray’s impressive military career.

Serendipity and chance

Above: Gerard ‘Del’ Delaney (left) presents James Murray’s original Great War Victory Medal (detail below) to his great-grandson, John Murray.

In 2019, over half a century on from the 1963 Fenian Street disaster, two people met for the first time at the Dublin Fusiliers’ Arch at St Stephen’s Green, the memorial to the men of that regiment who died in the Second Boer War. One was Gerard (‘Del’) Delaney, originally from Dublin and now living in the UK. A decorated former soldier with the Royal Logistic Corps, he actively participates in commemorations and archaeological excavations on the Western Front. The other person was the present writer, a great-grandson of James Murray, who had been researching his ancestor’s life story for several years beforehand. Serendipity and chance had led to this encounter.

Some years previously, Del had inherited several old family medals from his mother. One of them, a somewhat battered First World War Victory Medal, clearly bore Private James Murray’s name, regiment and soldier number on the rim. Del had never been quite sure how James’s medal came to be in his family’s possession, particularly as no clear relationship could be traced back to him. He immediately, and instinctively, realised the importance of returning this precious item to James’s direct descendants. The wider Murray family had always believed that much of James’s story had been completely lost, particularly in the Fenian Street tenement collapse. The return of his Great War medal represents the restoration of a very tangible link to their shared past and they are deeply grateful to Del Delaney for kindly facilitating this. Their ancestor James Murray was an ordinary man, living through quite extraordinary times. His story is one of bravery in the face of adversity but is also a reflection of working-class life for so many Dubliners during that turbulent period of Irish history. It emphasises the importance of resilience and fortitude.

John Murray is a lecturer in the School of Natural Sciences at NUI Galway and a great-grandson of James Murray.

FURTHER READING

T. Burke, Messines to Carrick Hill: writing home from the Great War (Cork, 2017).

K. Kearns, Dublin tenement life—an oral history (Dublin, 2006).

I. Passingham, Pillars of fire: the Battle of Messines Ridge, June 1917 (Staplehurst, 2012).