Irish Home Rule: stepping-stone to imperial federation?

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Home Rule, Issue 1(Jan/Feb 2012), Volume 20

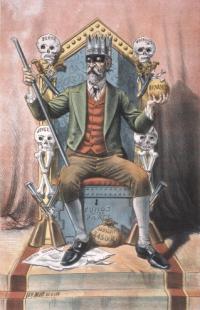

Charles Stewart Parnell as ‘The crowbar king’ by Tom Merry in St Stephen’s Review, 27 December 1890.

In 1888 Cecil Rhodes, an Englishman living in South Africa, donated £10,000 to Charles Stewart Parnell. His motive for contributing to a cause to which he had no emotional attachment is curious. The answer may lie in the manner in which Rhodes’s political ambitions were dependent on the Home Rule bill, and therefore on Parnell. The first Home Rule bill of 1886 failed because the Liberals split on the issue, partly because it did not provide for the retention of Irish MPs at Westminster. Irish MPs would instead serve only in a Dublin-based Home Rule parliament. English public opinion interpreted this as a desire by Ireland for clear separation from England.

Three letters exchanged

Parnell and Rhodes never met before the donation but exchanged three letters on the matter. Rhodes initiated the correspondence with a thirteen-page letter to Parnell on 19 June 1888, outlining his position on the Irish question. Both men subsequently exchanged one more letter each in that same month. In July 1888, with Rhodes’s agreement, Parnell published the correspondence in the then staunchly Parnellite Freeman’s Journal and the London Times.Analysis of Rhodes’s donation, worth nearly €1 million in today’s money, has been, until now, based on these newspaper articles. The National Archives of Ireland (NAI) holds copies of the three original handwritten letters, and when the newspaper articles and the letters are compared, word for word, a number of fascinating anomalies reveal an explanation for Rhodes’s staggering generosity. Notable segments of Rhodes’s first letter to Parnell were not published in the newspapers. Rhodes placed brackets around his text, suggesting that he intended these sections to remain confidential, which they did until now.

Punch cartoon depicting Cecil Rhodes as a colossus straddling Africa. (National Library of Ireland)

Rhodes began by making a persuasive argument for an amended Home Rule bill that would incorporate the retention of a reduced Irish representation at Westminster. This, he hoped, would establish the template for self-government or Home Rule for the colonies, including the Cape Colony. Rhodes, a leading Cape Parliament MP since 1880 and on the verge of becoming prime minister (which he achieved in 1890), believed that Home Rule could potentially confer upon him substantial political influence. Moreover, Rhodes echoed the frustrations of many British colonies with Westminster, which he considered as ‘over-crowded’ and concerned only with ‘the discussion of trivial and local affairs’.He envisaged a new model of imperial federation through an imperial parliament in which the political representatives from the colonies would discuss colonial matters. The Irish question was a ‘stalking horse’ and the ‘stepping-stone to that federation, which is the condition of the continued existence of our Empire’, he wrote. Non-retention of Irish MPs at Westminster, on the other hand, could consequently set a precedent for full separation and limit the ambitions of an imperial federation. The New York Times understood Rhodes’s motivation perfectly. It described the ‘handsome’ donation as a ‘little outburst, which struck everybody as somewhat queer, . . . now made pregnant with meaning by Mr Parnell’s statement that the Imperial Parliament, according to the plan, will contain representatives from all the colonies, and be a representative body, controlling the great English imperial federation’.So, Rhodes’s first letter, published in the newspapers, sought a ‘declaration’ that the Irish Party would support the retention of Irish representation at Westminster. Such a ‘declaration would afford great satisfaction to myself [Rhodes] and others, and would enable us to give our full and active support to your [Parnell’s] cause and your party’. Parnell was enthusiastic in his response:

‘. . . there can be no doubt that the next measure of autonomy for Ireland will contain the provisions which you rightly deem of such moment . . . I quite agree with you that the continued Irish representation at Westminster will immensely facilitate such a step [imperial federation].’

Rhodes’s response was immediate:

‘As a proof of my deep and sincere interest in the [Irish] question . . . I am happy to offer a contribution of the extent of £10,000 to the fund of your party.’

Thus, to the public mind, Rhodes’s stunning contribution was made following the acceptance by Parnell of the argument made by Rhodes on retention. In fact, Rhodes made the £10,000 commitment in his first letter, not the second. This section of the first letter was bracketed, indicating that it was not for public consumption, and was therefore not published. In the newspaper article, the public were led to believe that Rhodes made a persuasive argument on retention, that Parnell accepted this position and that Rhodes subsequently offered a donation.

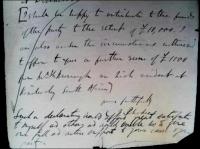

![Cecil Rhodes offers ‘a contribution to the extent of £10,000 to the funds of your [Parnell’s] party’ in his second letter of 24 June 1888.](/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Irish-Home-Rule-stepping-stone-to-imperial-federation-3.jpg)

Cecil Rhodes offers ‘a contribution to the extent of £10,000 to the funds of your [Parnell’s] party’ in his second letter of 24 June

1888.

But this was not an accurate representation of the sequence of events that led to the donation. In fact, Rhodes presented his views, together with the promise of a substantial donation; Parnell accepted; Rhodes responded by reiterating his promise of £10,000. This suggests that a quid pro quo existed between the offer of money by Rhodes and Parnell’s new policy on retention (a pragmatic position on which he and Irish public opinion were largely indifferent).Rhodes’s correspondence was coached in conditional language and it seems that a tacit understanding existed between the two men regarding the degree of subservience in which Irish representation at Westminster would be exercised. For example, in brackets, Rhodes described Home Rule as an ‘Irish Council’, though the newspaper version elevated it to an ‘Irish Legislature’. Rhodes also advised that Irish members should not ‘speak and vote even on purely English local questions, that of doubtful intervals they should be called upon to withdraw into an outside lobby’.

In reply to Parnell’s positive response (23 June) to his suggestion to retain Irish representation at Westminster. In fact, Rhodes made the offer in his original 10 June letter, but the sentence (in brackets, above) was excised from the published correspondence of July 1888. (National Archives of Ireland)

Other possible motives for Rhodes’s donation have been suggested. It may have been a pre-emptive measure against the Irish Party’s policy of obstruction, which required all-night sittings for the South African Cape Colonial question in the House of Commons. Or it may have been intended to ease the party’s implacable opposition to chartered companies and to guarantee Irish support for the grant of a royal charter to the British South Africa Company in 1889. Nevertheless, Rhodes’s donation of £5,000 to the Liberal Party in 1891—with the condition attached that the cheque should be returned if a future Home Rule bill failed to provide for Irish representation at Westminster—would suggest that the donation was to ensure a precedent for an imperial federation and one in which Rhodes saw himself as having a leading role.

‘Nakedness of the Nationalist treasury’

The value of the donation was complemented by its timing, coming as it did after a substantial drop in the Irish Party’s accounts. Parnell had confided to his brother just a year previously about the gravity of his financial affairs. ‘Well, John, politics is the only thing I ever got money from, and I am looking for another subscription now.’ Rhodes was aware of ‘the nakedness of the Nationalist treasury’ following a chance meeting on a boat to South Africa with J.G. Swift McNeill, a leading Irish Party MP. The 1885 and 1886 general elections, the demands of the Home Rule movement and the ‘plan of campaign’ had left the party financially exhausted. The account book of the Irish parliamentary fund reveals that its annual receipts declined from £10,762 in 1887 to £6,213 in 1889. Rhodes’s donation of £10,000 in 1888 was more than the total annual income of the party (£9,377) that same year. Edmund Dwyer Gray, proprietor of the Freeman’s Journal and son of the prominent Irish MP who shared the same name, referred to the conditional nature of the donation in a 1926 Tasmanian newspaper article. ‘Parnell was quite indifferent on the point [retention], but in any case £10,000 was a good persuader, and Parnell did what Rhodes wanted’—a view also shared by Swift McNeill in his autobiography. W.T. Stead, editor of Rhodes’ Last Will and Testament, asserted that his boss used ‘his wealth to put a premium upon certain policies’.

Second donation offer turned down in 1891

Dwyer Gray contends that Rhodes offered a further £10,000 in 1891, which Parnell turned down. Dwyer Gray’s account is subject to query, written as it was from the perspective of a then 21-year-old and some 35 years after the incident. Yet, why did Parnell turn down the second donation? Perhaps if it had come into the public domain, Parnell’s residual support from the Fenians, who would have balked at Rhodes’s imperial ambitions, would have been compromised. It may also have exposed Parnell’s innate conservatism on the Irish question. More intriguingly, why did Rhodes offer Parnell the second donation? Did he offer it on the condition that Parnell should stand aside so as to restore Irish Party unity, thereby locking the Liberals into their commitment to introduce Home Rule? (At the height of the Katherine O’Shea scandal Rhodes sent a three-line cable to Parnell—‘Resign, marry, return’.)Rhodes’s intervention in 1888 was successful. Parnell met the leader of the Liberal opposition, W.E. Gladstone, at his Hawarden home in 1889 to discuss a second Home Rule bill. Parnell briefed Rhodes immediately after this meeting. G.P. Taylor believes that this, by all accounts, was ‘quite unprecedented since he [Parnell] made no attempt to inform any of his colleagues in the Irish Party what had happened, and Rhodes appears to have been the only person Parnell did communicate with on the question’.Gladstone introduced the second Home Rule bill in 1893, which included the retention of Irish MPs at Westminster. This was also the case for the (third) 1912 Home Rule bill, the 1920 Government of Ireland Act and the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. At the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) annual conference in 1998, party leader Revd Ian Paisley, MP for North Antrim, told delegates: ‘What about Parnell? Oh, our enemies will say, “Sure, he was a Protestant”. Aye, a turncoat is always the worst.’ Yet, had it not been for the intervention of Rhodes, and Parnell’s acquiescence, Paisley might never have become a Westminster MP in the first place. HI

Elaine Byrne lectures in politics in Trinity College, Dublin, and is a political columnist. Her Political corruption in Ireland 1922–2010: a crooked harp? will be published by Manchester University Press in 2012.

Further reading:

R.P. Davis, ‘C.S. Parnell, Cecil Rhodes, Edmund Dwyer-Gray and imperial federation’, Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association 3 (21) (September 1974).Parnell–Rhodes correspondence, MS 697, 10 June 1888 (NAI).W.T. Stead (ed.), The Last Will and Testament of Cecil John Rhodes (Review of Reviews Office, 1902).G.P. Taylor, ‘Cecil Rhodes and the second Home Rule bill’, The Historical Journal 19 (4) (1971).