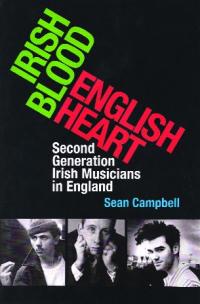

Irish blood, English heart: second generation Irish musicians in England

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Book Reviews, Issue 4 (July/August 2011), Reviews, Volume 19

Irish blood, English heart: second generation Irish musicians in England

Seán Campbell

(Cork University Press, €39)

ISBN 9781859184615

In the recent excellent Why pamper life’s complexities? Essays on the Smiths, co-edited by Seán Campbell and sociologist Colin Coulter, a recurring theme was the Irish heritage at the heart of the upbringing of members of the band. Those familiar with the politics and ideology of the band’s much-worshipped front man, Morrissey, were undoubtedly not surprised by a letter from the singer which appeared in Hot Press magazine just prior to the recent royal visit to Ireland. ‘The queen also has the power to give back the six counties to the Irish people, allowing Ireland to be a nation once again’, he wrote, in a letter that lambasted the institution of monarchy. He is one of many English-born musicians of Irish lineage to do so. Who could forget the reaction to Paul McCartney and John Lennon’s respective singles on ‘the Irish question’?

It is fitting that Seán Campbell’s most recent work, Irish blood, English heart, should take its title from a song of Morrissey’s. When he opened that song with the words ‘Irish blood, English heart, this I’m made of’, he perfectly captured the dual identity of many in Britain. As Campbell notes in his prologue to the work, the book’s title serves to ‘invoke the dilemma faced by second-generation Irish people, many of whom locate themselves as “half-and-half”’. One finds a generation who felt neither British nor Irish, unsurprising in the political and social context of the period under examination, which is 1980s Britain. Johnny Marr of the Smiths is quoted as saying, ‘I feel absolutely nothing when I see the Union Jack, except repulsion . . . and I don’t feel Irish either. I’m Mancunian-Irish.’

The work focuses on three musical acts, analysing three very distinct styles, personas and backgrounds: the Smiths of Manchester; Kevin Rowland’s Dexy’s Midnight Runners from the Midlands; and the infamous London-Irish punks, the Pogues. Other high-profile figures of Irish lineage are mentioned, such as John Lydon of the Sex Pistols, a.k.a. Johnny Rotten.

As an examination of British society in the period, the work provides excellent sociological insight into how the children of Irish migrants saw themselves fitting into, or not fitting into, British life. Shane MacGowan of the Pogues was of the belief that the second-generation Irish of late 1970s London had been ‘split down the middle, really heavily’, with one set of youngsters unashamedly Irish in outlook and culture, while others merely wanted to fit in to the native youth culture. Questions are raised around issues of assimilation or lack thereof, and it is clear that an overwhelming sense of ‘in-betweenness’ existed. As Campbell notes, terms and labels like ‘plastic Paddy’ became derisive allusions to the ‘perceived inauthenticity’ of the second-generation Irish. The second generation knew that they were very different from their parents and the native Irish. One of the strong points of Campbell’s work is his multidisciplinary approach and sources, and in a 1987 social geography essay on the Irish in London he finds a quote which perhaps best sums up the mentality of this second generation, alien to both the English and Irish: ‘Of course we know and enjoy Ireland, but London is our home, our city. We can’t recreate a lost Ireland in the middle of 1980s London.’

The book brings political events of the period into context wonderfully, showing the emergence of strong anti-Irish feeling among sections of British society in response to the rise of paramilitary activity in Britain and Northern Ireland. As Philip Chevron of the Pogues would note, ‘the only politics that counted in the London-Irish scene were the politics of being Irish in a place that was innately racist towards the Irish’. Following campaigns from red-top tabloids, and the implementation of the Prevention of Terrorism Act in the wake of the Birmingham bombing, for a period it appeared that the Irish community as a whole was seen as suspect. As one critic noted of Kevin Rowland’s attempts to ‘reconcile himself with his Irish roots’ on the band’s classic ‘Don’t Stand Me Down’ record, such out-and-out assertions of Irish pride or patriotism were ‘perceived in England as tantamount to wearing a balaclava and carrying a machine gun’.

Campbell has made great use of the archives of many influential music magazines, like Uncut, NME, Hot Press, Q, Melody Maker and other publications to the fore of youth and musical subculture in the UK and Ireland. It is within the pages of a much less mainstream publication, Sinn Féin’s An Phoblacht, that Campbell unearths a gem in the form of that publication’s praise for the Smiths: ‘With names like that who could doubt their antecedents?’ For a band often considered quintessentially British by many musical critics, Johnny Marr’s claim that ‘The IRA wanted to get up and make some speeches before we went on’ during a tour of the North is a surreal insight into how their anti-establishment ethos was viewed by some republicans at home.

Migrant experience and feelings of alienation come to the fore in this work, a highly valuable study of the Irish diaspora and the often forgotten ‘second generation’ in England. The book makes a strong and welcome contribution to cultural history and popular musical history, of course, but it triumphs within the field of Irish studies. It is perhaps a quote from Q magazine’s ‘100 Greatest British Albums’ special in 2000 that best captured the unusual nature of the Irish community. Including the Pogues among those featured, Q noted that ‘being white of skin and Western European of culture, Britain’s Irish are the invisible immigrants’.

When confronted by Melody Maker in 1985 on his Irish ethnicity, in response to the interviewer’s noting that ‘you were born in England’, Kevin Rowland retorted that ‘just because you were born in a stable doesn’t make you a horse’. Irish blood, English heart is a study of just some of the talented young musicians who emerged out of Britain’s largest migrant community yet lacked a clear sense of identity themselves. This sense of alienation and ‘in-betweenness’ was to prove central to the work, and appeal, of these great musicians. HI

Donal Fallon is editor of ‘Come Here To Me’, a blog of Dublin life and culture, http://comeheretome.com/.