Ireland, South America and the forgotten history of rubber

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (Jul/Aug 2008), Volume 16

An eve of 12 July bonfire—connecting Ireland to a longer and more disturbing history of ecological devastation. (Victor Patterson)

Every year, on the eve of 12 July, volcano-like pyres of car, truck and tractor tyres, wooden palettes and other combustible materials are ignited in neighbourhoods across Northern Ireland. For those who gather beside these infernos the symbolism of burning tyres is obscure. As the thick acrid smoke swirls into the summer night, stories are told and memories exchanged. The occasion has been condemned for the gratuitous environmental damage that it inflicts, but the extent of that damage runs deeper than an annual pyrotechnics show. These bonfires connect Ireland to a longer and more disturbing history of ecological devastation, and one with global implications, embodied in a somewhat neglected commodity: rubber.

Why is rubber so important?

A great deception of the free market is the way the gleaming products that tempt us wherever we look are separated from the modes of production. We are largely oblivious to the history of the products we buy. In the recent spate of ‘commodity histories’ rubber has escaped much scrutiny. Histories of cod, chocolate or bananas, for instance, are appealing subjects for understanding global exchanges and market interdependencies. Rubber, however, seems somehow obscure, dull even, but this reflects a history that is more complex to excavate and more disturbing to tell. Yet its importance for Western technological and economic expansion during the last century is incalculable. ‘We could recover from the blowing up of New York City and all the big cities on the Atlantic seaboard more quickly than we could recover from the loss of our rubber’, commented the tycoon Harvey Firestone in 1926. But why is rubber so important? And why has its impact on the environment been so extensive?

The argument could be made that rubber has changed the planetary ecology more dramatically than any other natural resource, with the possible exception of oil. In the latter half of the nineteenth century it was extracted from the tropical forests of sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and played a more significant role in the opening up of tropical interiors than is generally realised. In the twentieth century, once the main rubber-bearing tree, the Hevea brasiliensis, had been successfully transplanted via Kew Gardens to south-east Asia, vast hardwood regions of Indonesia and Malaya were cleared to make way for rubber plantations.

Demand for rubber unleashed waves of commercial adventurers into tropical interiors, and on the back of this rush arose countless rebellions, atrocities and local ‘slavocracies’—not wars in the traditional sense, but wars sparked by market forces and driven by men in search of fast fortunes. The story of rubber is one of almost biblical proportions telling of vast migrations, dispossessions and unrecorded crimes against both humanity and the tropical environment. In the Western hemisphere it was a principal commodity behind the great advances in manufacturing: electrification, the bicycle and automobile industries and heavy machinery all demanded increasing supplies of rubber. For the communities who dwelt in the tropical forests where latex-yielding plants grew, rubber brought with it none of the trappings of modernity. Instead it was synonymous with invasion, slavery and death.

The story of rubber is too immense, fragmented and tragic to fit easily into the comforting narratives describing Western economic progress. Rubber’s strategic and economic value lurks in the shadow of many key political decisions of the modern era. The race to control rubber-yielding regions was an obvious economic stimulus behind the European scramble for interior territories in central Africa and the Amazon. Profits deriving from King Leopold II’s fiefdom in central Africa financed some of the most lavish private and public building projects in central Brussels, including the royal palaces of Laeken and Tervuren. The Nazi war machine would never have mobilised without the successful production of synthetic rubber. In 1965, the overthrow of President Sukarno in Indonesia was driven by Anglo-American fears that vital rubber-producing territories might fall into communist hands. In assessing the business models of international rubber companies, such as Firestone, Goodyear, Dunlop and Michelin, the early strategies of transnational corporate enterprise can be understood.

County Dublin-born Garnet Joseph Wolseley (1833–1913)—one of the most significant players in the rubber industry and a close friend of King Leopold II of Belgium.

Irish involvement in the rubber industry

A number of significant Irish families were involved in the rubber industry. The County Dublin-born Garnet Joseph Wolseley (1833–1913), commander-in-chief of the British army and the most important soldier of the late nineteenth century, was a close friend of King Leopold II of Belgium and collaborated with him in the political negotiations and administrative organisation leading up to the Berlin conference of 1884, where he lobbied hard in support of Leopold’s claims to central Africa. His younger brother, Frederick York Wolseley (1837–99), emigrated to Australia and developed a sheep-shearing machine that revolutionised sheep-farming there. Returning to England in 1889, he established a factory in Birmingham and engaged Herbert Austin as foreman. By 1894 the factory had designed the first motorcar, although ill health drove Wolseley into early retirement. Shortly after his death, the machine tool side was sold to Vickers, Sons and Maxim Ltd, while the motor side was taken over by Austin and restyled the Austin Motor Co., which later became British Leyland.

Humanitarian activists

The inhumanity deriving from the rubber industry stimulated a network of activists determined to expose both the systems and the perpetrators responsible for the horrors. Irish nationalists, British socialists, church groups and international humanitarian organisations, such as the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines’ Protection Society, found common ground in campaigns against the rubber trade. In England a young journalist, E. D. Morel, began to speak out against the atrocities and was mentored and guided in his efforts by the Irish historian Alice Stopford Green. Green facilitated the necessary introductions that helped to establish Morel as an active voice condemning the destruction and inhumanity. She helped finance several of his projects, introduced him to her network of radical friends and had his articles placed in journals where she had influence.

In 1904 Morel and Green found a new ally in the British consular official Roger Casement, author of an official report condemning Leopold’s rubber-hungry regime. A meeting between Morel and Casement in the Slieve Donard Hotel in Newcastle, Co. Down, resulted in the founding of the Congo Reform Association and a sustained campaign to stir up international hearts and minds against the inhumane treatment of indigenous people. In 1906 Morel published his best-selling work Red rubber, relating the desperate saga of how international demand for a commodity could have devastating effects.

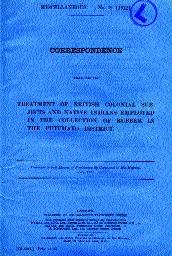

Casement took his crusade to Latin America. In 1910, as British consul-general in Brazil, he undertook an official investigation of the rubber industry in the north-west Amazon and made two journeys into the region in order to determine the treatment of British subjects and the extent of the devastation for indigenous forest communities. Using his diplomatic contacts, pressure was applied at the very highest level. The British ambassador to Washington, James Bryce, commented in a letter to the US secretary of state in May 1911:

‘It is no exaggeration to say that this information as to the methods employed in the collecting of rubber by the agents of the company surpass in horror anything hitherto reported to the civilised world during the last century. Flogging, torturing, burning, starving to death, have been in this ill-fated region, constantly and ruthlessly employed in the collection of rubber by the agents of the company their tyrants, while the brutal lust and hideous cruelty wantonly practised on the women and children deepen, if possible, the horrors of the scene.’

‘It is no exaggeration to say that this information as to the methods employed in the collecting of rubber by the agents of the company surpass in horror anything hitherto reported to the civilised world during the last century. Flogging, torturing, burning, starving to death, have been in this ill-fated region, constantly and ruthlessly employed in the collection of rubber by the agents of the company their tyrants, while the brutal lust and hideous cruelty wantonly practised on the women and children deepen, if possible, the horrors of the scene.’

Casement’s Blue Book, published in 1912, hastened the financial collapse of the extractive rubber market in the Amazon. Investment in the market now shifted from latex extraction to the new market for plantation rubber in south-east Asia. Decades of unregulated activity had left the region in tatters. The issuing of a papal encyclical Lacrimabili Statu Indorum by Pope Pius X was too little too late. Various missionary groups departed for the region in an effort to protect the remnants of the communities.

A group of five Irish missionaries—Fathers Leo Sambrook, Cyprian Byrne, Frederick Furlong, Felix Ryan and Edwin O’Donnell—arrived in the region in 1913. Not to be outdone, British Protestants, affronted by the Peruvian government’s insistence on and support for a Catholic mission, decided to send various unauthorised delegations. The Evangelical Union of South America despatched three of their most intrepid preachermen, Frederick C. Glass, Elliott T. Glenny and O. R. Walker, but they received no cooperation from local officials and could do little more than report on the extent of the devastation. The Irish Franciscans had more success; they established a mission station at La Chorrera and stayed on for several years, giving what help they could.

Rallying concern for international labour

By 1914 the story of rubber had become a rallying concern for international labour organisation, exhibiting, as it did, the blind excesses of the age and the callous irresponsibility of international business. James Connolly wrote an essay in The Irish Worker shortly after the outbreak of war denouncing Belgian rubber atrocities in the hope of dissuading Irish men from enlisting. Outrage about rubber atrocities galvanised international cooperation, and its shadow lived on in the negotiations leading to the founding of the League of Nations and the 1948 Declaration of Human Rights.

The horrors of the Western Front helped modernity to forget the crimes wrought by the extractive rubber industry. In the inter-war years in the Western hemisphere, rubber was designated a ‘strategic material’ and the old Anglo-Dutch trading alliance took control of most of the world’s supply produced by south-east Asian plantations. During the 1920s the US sought ways of breaking the monopoly and various projects were hatched. The economic regeneration of Liberia was planned by turning the country into a vast rubber plantation. Equally ambitious and disastrous was the project attempted by the Ford Motor Company to plant a massive area of the Amazon with rubber trees and create a sustainable source for rubber on the American continent capable of meeting the company’s requirements. Fordlandia, as this rubber production complex was called, ranks among the greatest business follies in Latin American history. Tree blight stunted the growth of the saplings and led to the complete abandonment of the project within a few years.

In the present struggle to stem the rapid environmental degradation of the planet, there is a pressing requirement to rethink world history in ways that awaken people to the magnitude of the crisis we face. In the rush towards modernisation, stories that interfered with the triumphal narrative of ‘progress’ were discreetly suppressed and forgotten; the tragedy of rubber extraction is one such story. Continuing deforestation of tropical hardwoods, which supply department stores, garden centres and supermarkets with cheap ‘teak’ garden furniture, is part of a sustained process of destruction. One wonders whether, if the history describing the human and environmental cost of rubber were more widely known, our attitudes and actions would be changed for the better?

Casement’s Blue Book, published in 1912, hastened the financial collapse of the extractive rubber market in the Amazon. As a result, investment in the market now shifted from latex extraction to the new market for plantation rubber in south-east Asia.

Angus Mitchell is currently undertaking an action research project in development education at the University of Limerick funded by Irish Aid.

Further reading:

W. Davis, One river: science, adventure and hallucinogens in the Amazon Basin (New York, 1997).

B. Weinstein, The Amazon rubber boom 1850–1920 (Stanford, 1983).

H. and R. Wolf, Rubber: a story of glory and greed (New York, 1936).