Ireland ‘slam-dunked’: basketball at the 1948 games

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2012), Volume 20

Members of the Irish basketball team enjoy refreshments during the 1948 Olympic Games—Pat Crehan (left) serving Frank O’Connor and Harry Boland, with Paddy Sheriff to the rear (with ball). (Basketball Ireland)

The proximity to London in 1948 encouraged several Irish federations, including basketball, to sample the Olympic menu for the first time. In 1945 the Amateur Basketball Association of Ireland (ABAI) was founded with the intention of introducing the game to the civilian population. Prior to this it was confined to the army. The version of the game played in Ireland at this time was significantly different to the international model. The ball used—remembered as ‘a cross between a Gaelic football and a medicine ball’ by Harry Boland, a member of the 1948 team—was bigger and heavier than the regulation ball of the contemporary international game. The army-dominated game was based on a version of a rulebook produced in 1936 and that had been considerably revised internationally; news of these revisions had yet to reach Ireland. International basketball disallowed physical contact; Irish basketball was intensely physical, closer to an indoor version of Gaelic football than to international basketball.

The Irish cabinet in 1948, with the minister for defence, Dr T.F. O’Higgins (front row, second right)—his cooperation, and that of the army authorities, was essential if the mission was to be accomplished.

Army authorities initially reluctant

Officials of the ABAI viewed participation in the London Olympic basketball competition as a logical progression in the development of the sport in Ireland. The cooperation of the minister for defence, Dr T.F. O’Higgins, and the army authorities was essential if the mission was to be accomplished. The army authorities were initially reluctant to cooperate with the ABAI’s project. On 31 May 1948, ABAI officers requested permission to send a deputation to the minister for defence ‘to discuss training facilities for members of the Olympic team’. A detailed outline of the ABAI requirements was forwarded to the minister’s office. Twenty-two soldiers had been chosen for intensive coaching and training prior to the final team selection, and permission was sought for their release from ordinary military duties and their transfer to Dublin. Permission was also sought for the use of the army gymnasium at Portobello Barracks. The ABAI pointed out that it was an all-Ireland association and internationally affiliated. The minister was not impressed. The ABAI officials were informed that ‘no useful purpose would be served by receiving the deputation proposed’. The request for training facilities was also refused. The chief-of-staff had briefed the minister that ‘a team of army players would not be of international standard’ and they would not ‘give a performance of sufficiently high standard to bring credit to the country and the army’. The ABAI officials were not prepared to abandon their project. In a response to the minister (22 June 1948) the ‘real sense of disappointment’ created by the decision was articulated. It was ‘comfortably anticipated the facilities asked for would have been readily granted’ in view of the ‘prominent part basketball has played in the physical training of the army for over twenty years’. A meeting was eventually arranged between representatives of the interested parties, and another written and more deferential request was made to the minister on 30 June 1948. On this occasion the ABAI secretary, A.M. Kelly, ‘respectfully’ sought the release from military duties and the transfer to Dublin of ‘24 officers, NCOs and men’ for ‘an intensive course of training and coaching’. A detailed itinerary was supplied and it was made clear to the minister that the Irish Olympic Council was responsible for the travel and accommodation expenses of the team whilst the ABAI was responsible for the insurance of the team. The following day Minister O’Higgins approved the various requests.

Harringay Arena—where the competition was staged between 30 July and 13 August—was a popular boxing venue that survived the bombing of London unscathed and had the capacity to seat over 10,000

Dominance of Western Command

The perseverance of the officers of the basketball association was admirable and their ambition to provide the players with international experience commendable, if somewhat naive. The 22 army players were selected for the ‘intensive period of coaching and training’ and the adjutant-general’s office instructed these players to report to Portobello Barracks on 5 July. This initial period of training ended three days later, following which the panel of players to travel to London was selected. Six opted not to attend the initial trial period; four more failed to gain selection and were returned to army duties. The selected panel then continued with the training programme until their departure for London on 24 July. Of the twelve army players chosen, six were from Western Command and based in the Custume Barracks, Athlone; four were from Eastern Command and two from the Curragh Command. This reflected the dominance of Western Command in army basketball at the time. The men from Athlone lost only once (in 1945) in the Army Basketball Championships between 1941 and 1951, and in 1947 completed a clean sweep by winning all seven basketball competitions available to them. Two players were selected based on their reputation, as they were unavailable for the initial trials. Lt James Flynn was completing an officer’s course and travelled separately to London, whilst Sgt Bill Jackson was representing Western Command in the army shooting championships. He was unable to join the main party until the day of departure for London. Jackson was the best-known athlete on the panel and played on the Roscommon team that won successive All-Ireland senior football titles in 1943 and 1944. Frank O’Connor from Caherciveen also represented Kerry in Gaelic football. There was also a strong family connection within the panel, as the two Sheriff brothers and Bill Jackson were married to sisters. The only civilian to make the panel was Harry Boland, a man steeped in the traditions of the GAA and Irish nationalism. Boland was friendly with Fr Horan, one of the great disciples of spreading the gospel of basketball to the civilian population, who introduced him to the game. Boland was secretary of the UCD hurling club and was impressed by a number of aspects of the game and its management, such as the use of two referees, separate scorekeepers and the time-keeping clock. Horan was a founder member of the UCD basketball club and ‘inveigled’ Boland to join. It was an ecumenical club in the sporting sense and attracted members from the various football codes played in the university. Harry Boland attended some informal trial games at Portobello with another civilian player, George McLoughlin. Boland played in the centre and was sufficiently impressive to gain selection for the London Olympics. McLoughlin was also selected but didn’t travel.

No ‘Olympic village’ accommodation

The basketball team travelled with the main body of competitors and departed from Westland Row Station on the morning of Saturday 24 July 1948. They travelled to Dún Laoghaire and from there by steamer to Holyhead. The rail journey from Holyhead to London’s Euston Station was completed late on Saturday. The athletes arrived in the city tired and hungry, as dining cars were not provided from Holyhead to London and the stops at intermediate stations did not allow sufficient time to obtain tea at station buffets. The supply of sandwiches brought by officials did not compensate for the absence of a decent meal on the journey. Shortly after midnight the team members arrived at the Willesden Technical College on Denzil Road, where the college’s classrooms were converted to temporary dormitories for the duration of the games. This was the team’s base for the duration of the Olympics. In the austerity of post-war Britain, the notion of constructing an Olympic village was never considered. Unfortunately the basketball players did not enjoy the privilege of participating in the opening ceremony. Neither the ABAI nor the Irish Olympic Council had the finances to provide the team members with an official uniform. The army authorities provided the playing kit of green singlets and khaki pants and these had to be returned at the end of the competition.Basketball was part of the Olympic programme for only the second occasion after its introduction in 1936. Twenty-three nations entered the competition, which was played at the Harringay Arena between 30 July and 13 August. The arena was a popular boxing venue that survived the bombing of London unscathed and had the capacity to seat over 10,000 people. Unfortunately only 200 attended the opening match, as basketball was virtually unknown in Britain at the time. The teams were divided into four groups, with the four leading teams from the 1936 Berlin Olympics ranked as a top seed in each group.

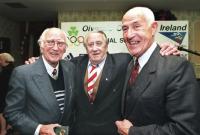

Harry Boland at an Olympic Council of Ireland 50th anniversary celebration of surviving Irish competitors from the 1948 London games in 1998. (Eric Luke/Irish Times)

Irish players overwhelmed

This system was ideal for nations such as Ireland seeking international experience, as it guaranteed a minimum of four matches to each nation. Unfortunately, the initial misgivings of the military personnel were more than justified by the results. The Irish players lacked the requisite pace, physique, strength, power, skill and experience and were overwhelmed. Only two of the players were over 6ft in a competition in which the USA fielded five players who were almost 7ft tall! The coaching of the team was also an issue. Comdt Donald McCormack and Sgt Charles Cleary from the Curragh Command were in charge of the coaching and training duties. These men had little knowledge of basketball and prepared a team that participated in a competition in which eight of the competing nations used American coaches. Not all their coaching interventions were for the good of the team, as Fr Horan was later to recall. The expertise of the Athlone players was under-utilised. ‘The coach, Commandant McCormack, knew very little about the game. He wouldn’t listen to the Athlone players, considering them mere privates in the army.’The virtual novices were out of their depth and were slaughtered in each match played. Problems with transport for Ireland’s opening game added to the complexities of the international debut. The bus arranged to collect the players arrived late at Willesden College and the driver lost his way on the journey, so that the Irish team arrived at the Harringay Arena twenty minutes late. The team members had to change into their playing gear en route to the venue and step onto the court without the benefit of even the most rudimentary warm-up session. The official report issued by the Irish Olympic Council after the games recorded that ‘This incident had a very upsetting effect from which the team never fully recovered’. The match provided a torrid introduction to international basketball for the Irish. Bill Jackson, Tommy Keenan, Jim Flynn, Dermot Sheriff and Christy Walsh were the starting five for Ireland and within a matter of minutes it was clear that the Irish were outclassed. The Mexicans established a 10–0 lead and then replaced their entire first-team squad and held them in reserve for the rest of the match. Paddy Crehan and Jimmy McGee replaced Sheriff and Walsh during the first half. At the interval the Mexicans led 34–4, and in the second half Frank O’Connor, Patrick Sherriff and Tommy Malone were introduced to Olympic basketball. Under the rules of the time only five substitutions were allowed. The Mexicans’ superiority in speed and technique was reflected in the 71–9 final scoreline, while Flynn, Crehan, Walsh and Keenan enjoyed the consolation of scoring Ireland’s first points in Olympic basketball. Although outclassed in the group games, the contemporary reports in the Irish Independent were diplomatic in their description of the Irish performances. Although well beaten 49–22 by Iran in the second match, the players displayed ‘a marked improvement in technique’ but ‘lacked the speed essential for top class competition’. Against Cuba the team were ‘executing with fair success moves that were not in their repertoire when the competition started’. The players could hold their own with any in high catching and were ‘adept dribblers’. Unfortunately, ‘in technique and team-work they were still a long way behind, and quite their weakest point was their marksmanship and the inability to score on the run cost them several chances’. The French ended the group games misery with a 73–14 victory in a match that featured Harry Boland and Donal O’Donovan, which ensured that all thirteen members of the panel gained some Olympic game-time. The Mexican team eventually lost in the semi-final to the USA, who then went on to beat France in the final. In Ireland’s final ranking games the team was beaten by the novices of Great Britain (46–21) and by Switzerland (55–21). The team finished in 23rd and last place overall. Despite the claim in the self-serving official report that the experience gained in London would enable Irish basketball to give a better account of itself in 1952, it was impossible to extract any positives from the venture. Ireland has not competed in the final stages of Olympic basketball since 1948. HI

Tom Hunt is researching and writing the official history of the Olympic Council of Ireland and of the Irish at the Olympics.

Further reading:

J. Hampton, The Austerity Olympics: when the Games came to London in 1948 (London, 2008).B. Phillips, The 1948 Olympics: how London rescued the Games (London, 2007).