The Ireland of Edward Cahill (1868–1941): a liberal or a Christian state?

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2017), Volume 25THE ACCELERATION OF CHANGE AND THE INTENSIFIED PACE OF LIFE HAVE MADE THE WORLD OF EDWARD CAHILL SEEM A LONG WAY OFF, EVEN THOUGH IT IS STILL WITHIN LIVING MEMORY

By Thomas J. Morrissey SJ

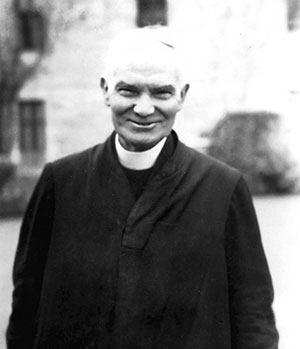

Above: Edward Cahill SJ—in the 1920s and 1930s his name and writings were well known in Ireland.

Ireland for much of his life had been a British possession. There was a constant political drive for Home Rule, which changed to a demand for fuller independence. The final eighteen years of his life were spent under an Irish government. Under both governments, however, many basic realities remained the same: there was widespread poverty, migration from the countryside into the towns and cities, and emigration to Britain and the United States of America; agriculture remained the country’s main industry, 92% of the population were Catholics and the vast majority practised their religion to some degree. Despite the extensive manifestations of religion, Cahill feared a progressive encroachment of liberal secularism into Irish life.

Family background

Edward Cahill had a happy childhood as one of eight children on a farm in west Limerick. Early in life he showed strong signs of patriotism and of social concern for the less well-off. Like his friend in adulthood, Éamon de Valera, also from a Limerick rural background, he became concerned to improve the lot of the small farmer and the landless labourer. Social commitment, strong religious belief and patriotic concern for the welfare of his country were intermingled in his life and determined much of his activity in the final quarter of his career.

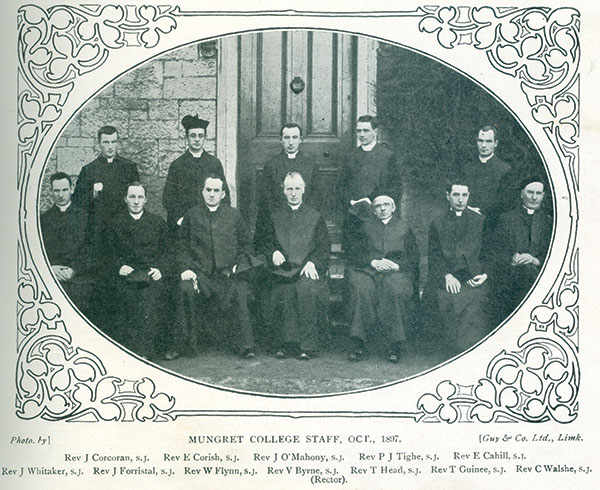

At the age of sixteen he entered the seminary for Limerick diocese at Mungret College. After obtaining a BA from the Royal University of Ireland, he went to Maynooth to study theology. Coming up to his ordination, he joined the Jesuits. After some years of further training, he was ordained and then sent back to Mungret to teach in the college’s Apostolic School. He spent twelve years there, first as teacher, then as director of the Apostolic School and finally as rector of the entire college. The Apostolic students were young men destined to work as priests across the English-speaking world. Edward brought to their formation the highest ideals. Many have thought that those years were the high point of his career. Numerous priests in North America, South Africa and Australasia paid tribute to the grounding he had given them in prayer, spirituality, education and love of country.

Above: Mungret College staff in 1897—Edward Cahill is the last on the right in the back row.

Edward’s patriotism, however, became a problem for his provincial superior. He was deeply interested in the Irish language, and through it became friendly during 1914–15 with a number of members of the Irish Volunteers. He also ran a boys’ cadet corps in the school. In 1917 he was transferred to Clongowes Wood College and from there to Milltown Park, Dublin, where he was given the task of teaching church history to Jesuit theological students drawn from all over the world. For many years he had read widely in Irish and European history.

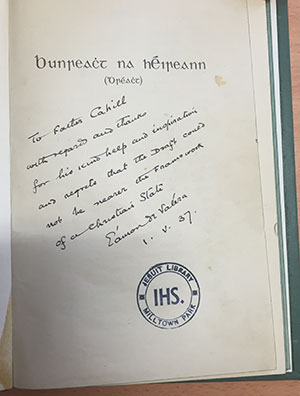

Above: Éamon de Valera’s handwritten dedication to Edward Cahill on a copy of Bunreacht na hÉireann, 1 May 1937. (Jesuit Library, Milltown Park)

In 1920 he was reappointed to the Apostolic School, which had wilted in his absence. It was a troubled time. Two of his close friends, successive mayors of Limerick, were murdered by the Black and Tans. In 1923 he had the first of the breakdowns in health that were to mark the remainder of his life. After a time in hospital, he returned to Milltown Park to teach church history and sociology. He had been reading the works of Auguste Comte and had been impressed by his influence. He longed, however, for a sociology more favourable to Christianity. When none appeared, he set about the task himself, basing his teaching on the social principles of Pope Leo XIII. Following a very extensive programme of reading, he embarked on a remarkable series of articles on Christian sociology in the Irish Monthly. The series continued for a number of months. At the same time there were articles on a range of other subjects, including ‘Patriotism’, ‘The Political State of Medieval Ireland’, ‘The Modern Labour Problem, Modern (or Unchristian)’, ‘Capitalism, Ireland’s Peril’, and numerous articles on different aspects of Freemasonry.

In his sociological and historical studies Cahill became convinced of the problem posed for Catholicism by Liberalism. ‘Liberalism’ is frequently identified in later times with concern for freedom and human rights, but Cahill, looking to Liberalism in mainland Europe in the nineteenth century and its subsequent history, saw it as a secular outlook that excluded mention of God from public life and undermined Christian values. He also saw it as advocating the laissez-faire capitalism that caused so much exploitation and suffering. At a time when Catholicism in Ireland seemed to be flourishing, he feared for its future. The Irish people had been subjected to Liberalism for more than 100 years and their values were more undermined than appeared on the surface. Moreover, the values of economic liberalism, or laissez-faire capitalism, had become part of Irish business life. His research indicated to him that a key driving force in Liberalism was Freemasonry, with its wide network of lodges and secret membership. His many articles on Freemasonry gave rise to a book in 1930 entitled Freemasonry and the anti-Christian movement. It proved controversial. The fact that it was marked by careful research and the reading of original sources resulted in favourable reviews in Catholic publications in Britain, America and mainland Europe, and in some non-Catholic works. It ran to a second edition.

Meantime, following the papal advice to involve lay people in the Church’s apostolate, Cahill gathered around him a number of men drawn from all backgrounds who were interested in social reform and in Christianity. To them he lectured on Catholic sociology, and from his meetings with them emerged the organisation known as An Rioghacht. It supported his ideas and his writings, and played an active part in Catholic Action in the 1920s and 1930s. Among the aims of its members was the development of the New Ireland into a Christian state. It was an idea and aim that had considerable support. The means to it was to be the papal social teaching. Fr Cahill felt that his friend de Valera had similar ideals. Towards the formal Christianising of Ireland, Cahill produced his largest book, The framework of a Christian state.

Commission of Inquiry into Banking

With de Valera in government and plans for a new constitution, it was natural for de Valera to ask Fr Cahill for proposals regarding the constitution. This led to a Jesuit committee being formed and a draft document being brought to de Valera by Cahill. Not content with that, Cahill also added suggestions of his own. Around the same time, two members of An Rioghacht were appointed to the Commission of Inquiry into Banking (1934–8). They, like Fr Cahill, viewed banking as a means to serve the people and not just as a purely profit-making enterprise. They emphasised a social side to economics; and they believed that to establish true social and political reform the country should have its own independent currency. The Banking Commission was divided in its final report. The majority of members, however, followed a conservative line resistant to change. It proved a triumph for the Department of Finance and a setback for de Valera, members of An Rioghacht and other supporters of reform.

Edward Cahill spoke out strongly against the majority report, which had been supported by the one Catholic bishop on the commission. In this, as in some of his writings, he was subjected to severe censorship from within the Jesuit order. It was a difficult era for religious superiors. The anti-Modernist spirit still reigned, fresh ideas in theology or social teaching could easily be misconstrued, and politically the wounds of the Civil War were still raw and allegiances were polarised.

In his final years Edward kept writing. In a year and a half he produced a number of articles and pamphlets, as well as actively promoting a plan he had for lessening the migration from the countryside to the towns and cities. In 1941 he had his final bout of sickness. After a long illness, endured with much patience, he died on 16 July. Next day, the various newspapers chronicled his death with laudatory headlines. His funeral at the Jesuit Church, Gardiner Street, Dublin, was attended by a large number of clergy, and in attendance were Taoiseach Éamon de Valera and Mrs de Valera, some members of the Dáil and the Senate, and a wide range of friends and acquaintances. He would have been surprised, had he lived, to find that within a decade a number of his and An Rioghacht’s proposals for the improvement of the country were taken up by Clann na Poblachta, and that Seán MacBride had among his advisers some members of An Rioghacht.

Personally, Edward Cahill was remembered for many years as an author, a leading figure in the many-sided Catholic Action movement, a lover of his country and its language, and a man who by his enthusiasm and Christian idealism, in the aftermath of Civil War, bonded men and women together in the quest for social reform in a new Ireland. Finally, he was remembered as a kindly, approachable man who had time for others and especially for the poor.

Above: The house today in Ballyvocogue, Cappagh, Co. Limerick, where Edward Cahill was born in 1868.

Thomas J. Morrissey SJ is the author of The Ireland of Edward Cahill SJ, 1868–1941—a secular or a Christian state? (Messenger Publications, 2016).

FURTHER READING

E. Cahill, The framework of a Christian state (Dublin, 1932).

P. Corish, The Irish Catholic experience: a historical survey (Dublin, 1985).

M. Curtis, The splendid cause: the Catholic Action movement in Ireland in the 20th century (Dublin, 2008).

E. Larkin, The historical dimensions of Irish Catholicism (Washington DC, 1984).