Ireland and the Bolshevik Revolution

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2017), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 25‘A blow delivered against the British imperialist bourgeoisie in Ireland is a hundred times more significant than a blow of equal weight in Africa or Asia’ (Lenin on the 1916 Easter Rising).

By Jérôme aan de Wiel

In April 1917 the Germans sent Lenin aboard a sealed train from Switzerland to Russia with the aim of starting a revolution and knocking Imperial Russia out of the war. This was part of Imperial Germany’s Revolutionsprogramm, a strategy conceived to foment trouble in enemy territory. It had failed in Ireland a year before with the defeat of the Easter Rising led by the republican Patrick Pearse and the Irish Volunteers and the Marxist James Connolly and the small Irish Citizen Army. The Rising had not been unanimously welcomed by communist leaders. Karl Radek said that it was a mere ‘putsch’, while Trotsky warned that the next Irish revolution would have to have the support of the proletariat. Lenin, then living in exile in Zürich, was far more sympathetic, however, and wrote that ‘a blow delivered against the British imperialist bourgeoisie in Ireland is a hundred times more significant than a blow of equal weight in Africa or Asia’. In Russia, the October Revolution in 1917 was successful. Lenin spoke of ‘the triumphal march of Soviet power’; it was only a matter of time before it spread everywhere.

Brest-Litovsk, Wilson’s Fourteen Points and Ireland

The Bolshevik leadership decided to pull out of the war to capitalise on the revolutionary élan. Adolph Joffe, the leader of the Red delegation, arrived by train in Brest-Litovsk to meet the delegations of the Central Powers. He presented a document containing six points to guarantee a lasting peace. Point 3 concerned Ireland: ‘The possibility to decide freely for national groups within existing states to be attached to other nations or to become independent states’. On 31 December 1917 the US ambassador to Russia cabled Washington on the ongoing negotiations at Brest-Litovsk and included Trotsky’s peace programme stipulating that the fate of ‘Alsace-Lorraine, Transylvania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, etc., on the one hand, Ireland, Egypt, India, Indo-China etc., on the other [should be] subject to revision’; in other words, both the western Allies and the Central Powers should apply the principle of self-determination equally and honestly.

That was before US President Woodrow Wilson presented his Fourteen Points and his concept of self-determination on 8 January 1918. His secretary of state, Robert Lansing, was not carried away by self-determination and had said to the US’s French allies: ‘All peoples are not worthy of a republic. One needs an education to understand what it is.’ On 20 January Éamon de Valera, in favour of an Irish republic, reacted very cautiously to Wilson’s speech, publicly declaring that it remained to be seen whether he could be trusted. The Sinn Féin president could not have known how right his instincts were.

Reaction in Ireland

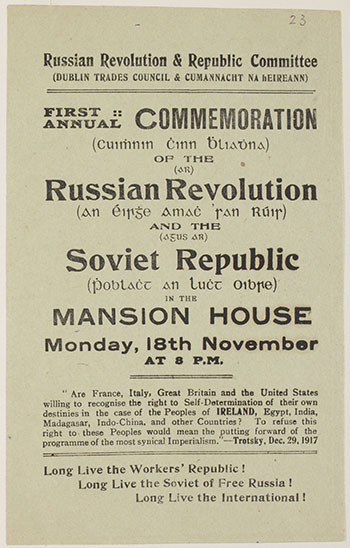

Above: Poster for a Dublin Trades Council commemoration of the first anniversary of the October Revolution in November 1918. The establishment of the Bolshevik government in Russia led to expressions of interest and hope in Ireland. (NLI)

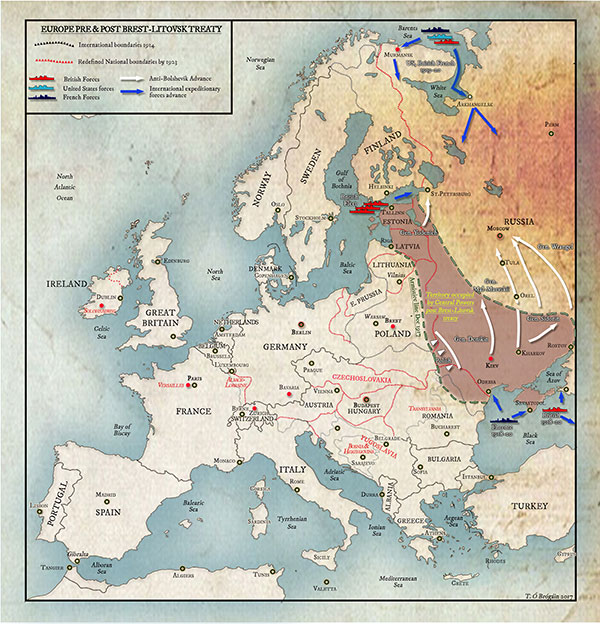

The establishment of the Bolshevik government in Russia led to expressions of interest and hope in Ireland. The pro-Home Rule Freeman’s Journal published Trotsky’s declaration on self-determination on 4 January 1918. In that same month the rather fractionary Irish Left sent a delegation to meet Soviet plenipotentiary Maxim Litvinov in London. Litvinov assured them that in Russia James Connolly was well known. Some 2,000km away, in Brest-Litovsk, the Germans and Russians eventually signed a treaty on 3 March 1918. The Bolsheviks lost much territory, but Lenin believed that Germany was about to be engulfed by revolution and that it was vital that peace be concluded so that the Central Powers were off Russia’s back, which would allow the Bolsheviks to consolidate their revolution and ensure its survival against the counter-revolutionary Whites and other internal enemies.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk had dramatic consequences for Ireland. The Germans could transfer their divisions from the eastern to the western front and deliver the knockout blow to the western Allies. Their offensive began on 21 March 1918 and at first seemed to be successful. David Lloyd George’s cabinet panicked and foolishly extended conscription to Ireland, also including, initially, members of the clergy! This ensured Catholic Church opposition. De Valera secretly liaised with Archbishop William Walsh of Dublin and conscription was defeated thanks to widespread passive resistance. It was the beginning of the end for British rule, as Sinn Féin became the driving force in Irish nationalism. On the western front, the German offensive petered out and defeat was now only a matter of time.

Meanwhile, the western Allies sent expeditionary forces to Russia, notably at Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. Lenin said that the country was effectively at war with France and Britain, yet he remained very upbeat. On 7 November 1918, the first anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution, he declared that ‘Germany has caught fire and Austria is burning out of control’. He appeared to be right. On 11 November 1918 Germany capitulated, and unrest and dislocation were gripping Germany and Austria-Hungary. Lost Russian territories could be retaken and Red flags could be seen in Berlin, Bavaria and Budapest. In December 1918 a political revolution was under way in Ireland, as Sinn Féin overwhelmingly won the general election. It demanded a republic and no partition.

Above: Lenin speaking in Red Square during the celebration of the first anniversary of the October Revolution in 1918. Commenting in exile in Zürich on the 1916 Easter Rising, he said that ‘a blow delivered against the British imperialist bourgeoisie in Ireland is a hundred times more significant than a blow of equal weight in Africa or Asia’. (Alamy)

On 21 January 1919 Dáil Éireann met for the first time in Dublin, declared Ireland’s independence and announced its intention to send a delegation to the peace conference in Paris. It also issued a ‘Message to the Free Nations of the World’, reiterating the reality of ‘national independence’. The British press largely mocked the event. The same day, at Soloheadbeg, Co. Tipperary, two policemen were shot dead by Irish republicans, marking the beginning of the War of Independence. De Valera was delighted when left-wingers Tom Johnson and Cathal O’Shannon argued in favour of self-determination in Berne during the Second (Socialist) International in February 1919. In that same month the British chargé d’affaires at Arkhangelsk informed London that messages from Moscow had been intercepted, indicating that the Soviets might appoint a representative to this new ‘Irish Constituent Assembly’ in Dublin. The Foreign Office replied that the Dáil was nothing to worry about.

The Bolshevik leadership might well have been interested in Ireland but had not been impressed by the meeting in Berne. In March the Comintern was founded and Moscow announced its intention to coordinate the worldwide proletarian revolution. Nikolai Bukharin declared:

‘If we propound the solution of the right of self-determination for the colonies … we lose nothing by it … The most outright nationalist movement … is only water for our mill, since it contributes to the destruction of English imperialism.’

Johnson and O’Shannon were discredited, and the ebullient and full-of-initiative Roddy Connolly, son of James, was now in the ascendant. In April Lenin said that ‘the revolution in Hungary gives conclusive proof that in western Europe the Soviet movement is growing and that its victory is not far away’. For European communists or those interested in communist support to achieve self-determination it all sounded very good and promising.

Versailles

Moscow’s voice was encouraging, especially since the Sinn Féin delegation got nowhere near the negotiating table in Paris. Confronted with old-style European diplomacy, Wilson lost much of his idealism but wanted his League of Nations project to see the light at all costs. He was therefore not going to upset the French, and especially the British. The US president did receive an Irish-American delegation but told it firmly that now was not the time to bother him with the everlasting Irish question. It was exactly as Trotsky had predicted: self-determination only concerned territories belonging to the defeated Central Powers. The Germans had been excluded from the peace negotiations and were there only to sign the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919. They refused, however, to support the Irish republicans, their allies of not that long ago, as they knew that the British were more favourably disposed towards their country than the vengeful French. Under no circumstances should London be upset about Irish independence.

The Bolsheviks too had a major problem with self-determination for Ireland: reality. Geography, civil war and economy were going to dictate strategy for Moscow. Berlin and Budapest were two revolutionary hot spots that were out of reach for the Red Army, and the Bolshevik revolutions in those two cities were soon crushed. By the spring of 1920 the Whites were as good as defeated in Russia, but it was at that moment that the army of the recently reborn Poland marched into Ukraine and took Kiev. The Red Army beat the Poles back but was decisively beaten by Józef Piłsudski during the Battle for Warsaw in August 1920. On paper, the Red Army looked formidable with its 4.6 million men, but in fact it was poorly trained and equipped. If Berlin and Budapest were out of reach and Poland could not be beaten, it was not even worth mentioning Dublin or Cork. Stalin wrote in Pravda that the Polish offensive had been orchestrated by the Entente powers (France and Britain).

Anglo-Russian Trade Agreement

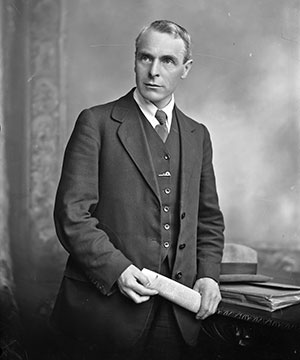

Above: Labour leader Tom Johnson—along with William O’Brien he met Russian Commissar of Foreign Trade Leonid Krasin in London, and reported in January 1921 to a meeting of Labour officials and Dáil ministers that the Russians had become far more moderate in their support for an Irish republic. (NLI)

Meanwhile, in London Lloyd George was opposed to any direct intervention in Russia, as it was too expensive. After the war the British needed to put their financial house in order. In November 1919 the prime minister had spoken of normalising relations with Bolshevik Russia. In the spring of 1920 the British began talks with the Russians to restore trade. The Bolsheviks were most definitely interested, as their country’s economy needed to recover before any large-scale foreign projects could be undertaken. On 16 March 1921 the Anglo-Russian Trade Agreement was signed by Commissar of Foreign Trade Leonid Krasin. The British ended their blockade of Russia and both sides agreed to cease hostile propaganda campaigns.

The trade negotiations had repercussions for Moscow’s commitment to self-determination for Ireland. Labour leaders William O’Brien and Tom Johnson met Krasin in London and reported in January 1921 to a meeting of Labour officials and Dáil ministers that the Russians had become far more moderate in their support for an Irish republic. Ireland’s condition was not favourable for a Bolshevik revolution, and that was all that Moscow was interested in. Several ‘soviets’ sprang up in Ireland and the red flag flew in many places, but these were isolated incidents whose importance should not be overestimated. The farmers had got much land back thanks to Land Acts introduced before the First World War. State property or collectivisation would have been immediately rejected. Newspapers regularly reported on Red terror in Russia and the regime’s war on religion. The Catholic Church warned against Bolshevik atheism. British intelligence conducted a campaign depicting Irish republicans as closely associated with the Bolsheviks.

De Valera knew that he had to remain cautious and remembered the power displayed by the Church during the conscription crisis. What if that power was suddenly directed against republicans? Despite Woodrow Wilson’s lack of enthusiasm for Ireland in Paris, de Valera set off to the USA, where he stayed from June 1919 until December 1920. His mission was to secure official recognition for the Irish Republic, to get support from the American people and to get money for the cause. The Wilson government never recognised the Irish Republic, however, and de Valera was soon at loggerheads with Irish-American republican groups and personalities, who had no desire to be bossed around by him.

McCartan’s mission to Moscow

Yet Dr Patrick McCartan, the Dáil’s envoy to the USA, had established contacts with Ludwig Martens, the Russian representative. In 1920 he negotiated a draft treaty with the Russians that stipulated the mutual recognition between the two revolutionary governments, the establishment of commercial relations and even the entrusting ‘to the accredited representative of the Republic of Ireland in Russia the interests of the Roman Catholic Church’. The last point was obviously meant to neutralise a possible Irish ecclesiastical backlash and was rather naïve. When shown the draft treaty, de Valera was not particularly enthused but told McCartan to send it to the cabinet in Dublin. He also wanted an Irish delegation to go to Moscow. The cabinet agreed, but only if nothing could be expected from the US government. Caution remained. In June 1920, however, the Dáil decided that a delegation should be sent with the aim of establishing diplomatic relations; the issue of the draft treaty was not broached. It was by now clear that de Valera’s American recognition tour was less successful than anticipated.

The Dáil’s decision was not unanimously approved. Sinn Féin diplomats George Gavan Duffy and Seán T. O’Kelly reported from Paris that Ireland’s emerging links with Bolshevik Russia were counterproductive and would further isolate Ireland on the Continent. Nonetheless, de Valera was now anxious that McCartan proceed to Russia but refused to grant him plenary powers. McCartan said that if a treaty was concluded he would ask the Russians to ship over 50,000 rifles. He eventually arrived in Russia on 6 February 1921. There he was sent on a political wild-goose chase. After several days of waiting, he first met Maxim Litvinov, who was, in the end, honest enough to tell him that ‘on account of conditions both inside and outside Russia it would be inadvisable for the Russian government to do anything for Ireland’. Litvinov also mentioned the importance of the current trade negotiations with the British.

McCartan then travelled to Moscow to meet Commissar for Foreign Affairs Georgy Chicherin. Again, he was made to wait several days before being granted a not particularly productive meeting. Chicherin said that the Irish republicans were ‘not in military control’ and even asked whether ‘if Russia gave [Ireland] recognition would the Irish people not expect more assistance than [Russia] could give [her]’? Of course, this was true after the Battle for Warsaw, but Chicherin was only looking for excuses to get rid of McCartan. According to McCartan, Chicherin was mainly interested in the Irish Citizen Army, not so much the republicans; he even said, correctly, that ‘[we] have been informed that [you] are hostile to communism’ and was convinced that the republican movement in Ireland ‘was inspired by American dollars’. Dollars had indeed been pretty much on de Valera’s mind when he embarked for the US. Finally, Chicherin came perhaps to the crux of the matter when he declared that ‘they could not assist [Irish republicans] with such things as rifles and ammunition’. McCartan would take the train and boat back home.

Roddy Connolly

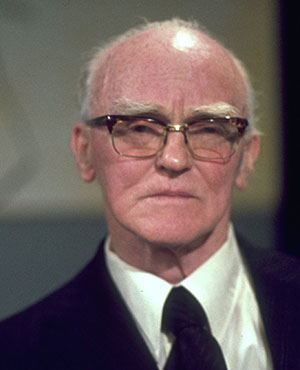

Above: Roddy Connolly in 1976. In the summer of 1921 he was in Moscow for the Third Comintern Congress. (RTÉ Stills Library)

As for Roddy Connolly, he was in Moscow for the Third Comintern Congress in the summer of 1921, during which little was said on colonial issues and far more on the failure of revolution in Europe. He met Lenin and gave him a report entitled ‘The conditions of Ireland, 1 July 1921’, outlining the latest actions of the IRA and his unrealistic belief that the population could embrace communism provided that ‘considerable extraneous assistance’ was provided—in other words, Russian assistance. He also felt that the republican leadership would eventually agree with the British on dominion status for Ireland. He was right on the last point. On 6 December 1921 Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty. A few months later the Civil War began, as the treaty fell far short of what de Valera and his followers wanted: a republic for the whole island. In London in February 1922 Leonid Krasin told Irish visitors that his government was willing to have ‘close political and commercial relations’ with the newly formed Irish Free State.

In July 1922, still in London, Connolly told Mikhail Borodin of the Comintern that the IRA would be able to wage guerrilla warfare, obliging the British army to intervene and resulting in the destruction of the Free State. Borodin did not mince his words: ‘It is my firm opinion that they will crush the republicans … It is really laughable to fight the Free State on a sentimental plea. They want a Republic. What the hell do they want a Republic for?’ Borodin was right in his prediction, but showed that idealism for small nationalities was only of interest to the Bolshevik leadership if it suited its interests at the right moment. In the end, early Irish–Soviet relations were realpolitik all round. It was only in the mid-1970s that both countries established official diplomatic relations.

Jérôme aan de Wiel lectures in history in the School of History, University College Cork.

FURTHER READING

J. aan de Wiel, The Irish factor, 1899–1919: Ireland’s strategic and diplomatic importance for foreign powers (Dublin, 2008).

E. Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War (Edinburgh, 2011).

A. Mitchell, Revolutionary government in Ireland: Dáil Éireann 1919–22 (Dublin, 1995).

E. O’Connor, Reds and the Green: Ireland, Russia and the communist internationals 1919–43 (Dublin, 2004).