Insurrection in the cradle of abolitionism

Published in Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2019), Volume 27The 1863 Boston draft riot.

By Joe Regan

During 1–5 May 1863, fighting raged in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, between the Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Outnumbered by more than two to one, General Robert E. Lee had caught the Union army of Joseph Hooker off guard at the village of Chancellorsville with a devastating flank attack. Confederate victory allowed Lee to audaciously launch his second invasion of the North. Dismayed and embittered by yet another military defeat, the Boston Pilot declared that

‘The Irish spirit for the war is dead! Absolutely dead! … It is a fact that our men have been exterminated in this war. Their desperate valor led them not to victory but extinction … How bitter to Ireland has been this rebellion! It has exterminated a generation of its warriors.’

After Chancellorsville, morale plummeted across the Northern states as they prepared for Lee’s invasion and the nation’s first Federal draft.

‘Rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight’

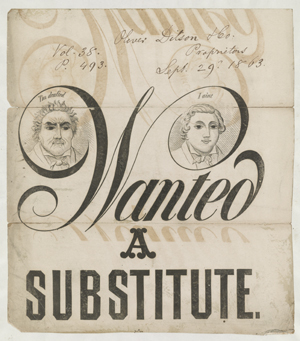

The prolonged attrition on the battlefield forced the Federal government to endorse measures such as emancipation and conscription that were unthinkable to most Americans at the outbreak of the Civil War. The Militia Act of 1862 proved inadequate to meet the Union’s demand for soldiers. In response, the Enrolment Act of 1863 was signed into law on 3 March 1863. Under this legislation the Federal government took direct control of the conscription process and could levy quotas on enrolment districts which had to be met by supplying volunteers or draftees. The Enrolment Act also stipulated the conditions of ‘alien eligibility’: all foreign-born males aged 20–45 were to be enrolled if they had declared their intention to become citizens, had voted or held public office. It did permit various exemptions for those with special circumstances, such as a physical disability. A draftee was also permitted to provide a substitute or pay a ‘commutation’ fee of $300 rather than serve. This fee, however, was the equivalent of a year’s income for a working-class man, and the commutation and substitution clauses gave rise to the cry of ‘a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight’. The Boston Pilot declared the new conscription laws ‘a miserable Yankee trick’ that targeted immigrants as ‘food for powder’. Such perceptions, combined with the disenchantment over emancipation among Irish-Americans, provoked violent reactions to the draft.

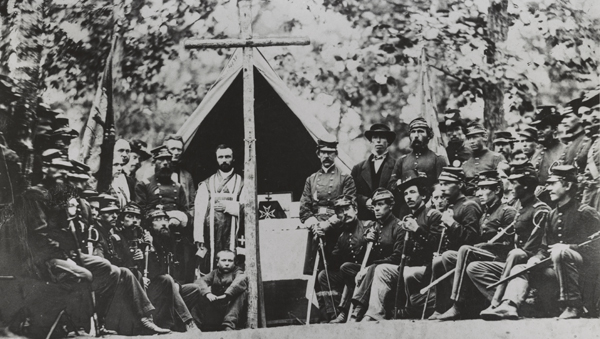

Above: The 9th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry celebrating Mass at Camp Cass, Arlington Heights, Virginia, in 1861. (Library of Congress)

The draft began in July 1863 in twelve states and the District of Columbia. Tensions bubbled up in Boston. After delivering a Fourth of July address to recently discharged nine-month veterans, encouraging them to re-enlist, Massachusetts governor John Andrew received an anonymous letter ‘on behalf of 29 such veterans’. The letter warned Andrew that ‘if you want white men to fight for the d—-d Negroes you must look somewhere else for them … “you” and your infernal abolition devils … are the whole cause of this damnable war’. The letter concluded with a promise to discourage enlistment and a threat to ‘join an organization that is already established in the city that can [and] will by force of arms’ prevent further enlistment. On 6 July 1863 Boston businessman Samuel Bowdlear noted that the draft had commenced in the city. He was of the opinion that ‘a good many who are liable to draft will find this a convenient time to rusticate. A physician’s certificate will not let you off now. All must go and submit to an examination by the surgeon of the Government.’ That evening, ‘a crowd of three or four hundred Irish people collected’ to beat two police officers who had arrested an Irishman by the name of William Nolan. After Nolan’s rescue, a meeting hosted by draft-eligible men in the city’s North End ended with cheers for the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis. In this volatile climate it did not take much to spark an insurrection in the cradle of abolitionism.

‘Kill the damnded Yankee son-of-a-bitch’

Above: ‘I’m not to blame for being white, sir!’ (Boston, 1862). This cartoon illustrates how many felt that Boston’s élite ignored the home-front deprivations suffered by the city’s working class. It attacks Massachusetts senator and prominent anti-slavery advocate Charles Sumner, who is depicted dispensing a few coins to a black child on the street while ignoring the appeal of a ragged white child. (Library of Congress)

In 1863 Boston had a population of about 182,000, of which the Irish numbered well over 50,000. The North End, where the riot occurred, was one of the largest Irish enclaves. Packed into squalid tenements, Irish immigrants eked out a bare existence as dock hands, construction labourers or domestic servants. Irishmen from the North End were heavily represented in the state’s two Irish regiments, the 9th and 28th Massachusetts Volunteers. These outfits suffered heavy casualties throughout 1862 and 1863. On the Peninsula, the 9th Regiment suffered more than 200 casualties. Similarly, the 28th, which had seen almost a quarter of its members fall at the Battle of Antietam, was transferred to the famed Irish Brigade for the Battle of Fredericksburg, where almost 40% of the regiment were killed or wounded.

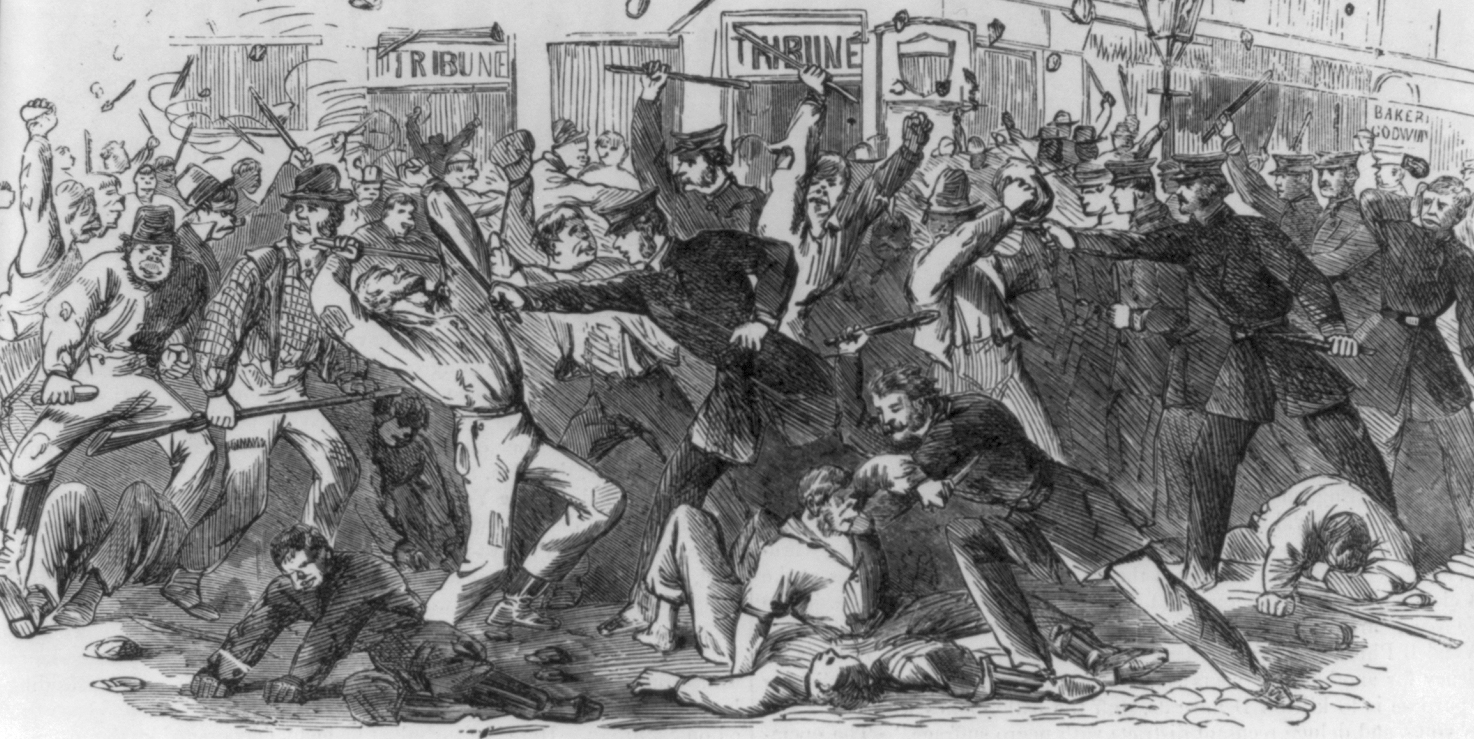

Organised opposition to the draft occurred in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York and Wisconsin. Across the Northern states mobs attacked and killed several enrolment officers during the spring and summer of 1863. On 12 July the worst riot in American history erupted in New York City, where mob violence terrorised the city for four days and left at least 105 people dead.

On the morning of 14 July, as news from New York reached Boston, the Catholic archdiocese of Boston held a special Requiem Mass in honour of the city’s fallen Irish soldiers. The heavy cost of victory at Gettysburg (1–3 July) became apparent with the fresh publication of the battlefield casualty lists. Trouble began about midday when the Irish residents of Boston’s North End began a scuffle with two provost marshals who tried to serve conscription papers. The fighting escalated with the arrival of additional police in the neighbourhood. The police were overpowered by an angry crowd of 200 or more throwing bricks and bottles. Several policemen were injured. One officer reported that the crowd severely beat him and that he barely escaped, being pursued by women and children who pelted him while screaming ‘Kill the damnded Yankee son-of-a-bitch’. In ‘a short while the whole North End was in a state of revolt’.

With the police routed, the crowd descended on Haymarket Square, where they began looting gun shops and hardware stores. The Boston Daily Advertiser reported how the square ‘presented an exciting scene, filled with a turbid mass of people, including many women and not a few children, with bayonets and knives quite plenty, glistening over their heads’. Around 8.30pm the armed crowd arrived at the armory on Cooper Street, where they were again greeted by police, as well as by the First Massachusetts Heavy Artillery under the command of Major Stephen Cabot. Upon hearing of the outbreak of violence, Governor Andrew had summoned the state militia and regular army troops from Charlestown, Cambridge, Somerville, Roxbury and Medford to put down the riot. He refused, however, to call upon the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment from Camp Meigs in Readville, as he feared that a regiment of African-American soldiers ‘could not safely be employed to put down a riot of free white American citizens’.

Above: ‘Wanted: a substitute’ (Boston, 1863). An illustrated sheet music cover which protests the inequities of the draft enacted under the Enrolment Act of 1863. The unfairness of the measure to the economically disadvantaged is dramatised in the contrast between the bust portrait of one man, ‘I’m drafted’, and that of an obviously more well-to-do young man, ‘I aint’. (Library of Congress)

On Cooper Street the crowd soon bombarded the armory with bricks. Among the brick-throwers the Boston Daily Journal reported ‘one Amazonian woman, shouting and screaming, and urging the assailants on in their desperate work … she rushed again and again to the assault’. According to Emma Sellew Adams, a middle-class eyewitness, to ‘repel the attack the troops fired blank cartridges but they had no effect, and, in fact, added fuel to the flame. The women came out in large numbers, some of them holding their babies up in their arms and daring the soldiers to fire at them. Finally gaining courage, the rioters crowded up against the doors of the Armory and tried to break them open.’ Outnumbered, Cabot gave the order to open fire into the crowd with howitzers, killing several. Adams recalled that the dead and wounded ‘lay on every side and the havoc was appalling, but this act quelled the riot’. As the crowd fell back, soldiers with fixed bayonets flooded the streets.

Boston remained in a state of emergency, with sporadic and smaller mêlées breaking out. At the time of the riots, Boston’s Catholic bishop, John Fitzpatrick, was in Belgium. The chancellor of the Boston diocese, James Augustine Healy, issued a circular to all priests ‘to use their utmost efforts to preserve the public peace among their congregations—to caution them not only against taking part in fractious assemblies, but even against being present at them’. Throughout the night priests patrolled the North End streets, admonishing loiterers. Nevertheless, Fr Hilary Tucker believed that there was still ‘a threatening and sullen look in the countenances of everybody that bodes no good. The general sentiment is that a great injustice has been done to the poorer classes.’

Wealthy Bostonians, however, were disgusted by the ‘fearful’ riot. Large segments of Boston’s political and economic élite viewed loyalty to the Republican party as loyalty to the Union. Those who took to the streets were deemed unpatriotic and disloyal. Samuel Bowdlear, for example, was outraged that ‘Jeff’s [Jefferson Davis] friends have at last waked up and are doing him good service, they won’t help the Government against the Rebels but they are willing enough to burn, destroy and murder at home’. Frightened, Bowdlear believed that the draft riots in Boston and New York were orchestrated ‘in conjunction with the southern Rebs and for the purpose of putting down our Government and forcing an ignominious peace’.

‘Those who get maimed in the war will have but a poor chance to make a living’

The Boston draft riot was not part of a Confederate conspiracy. It was a protest by the city’s immigrant and working-class community against an escalating war. The quick deployment of the militia and regular troops contained the violence to the city’s immigrant neighbourhoods. Boston was spared the destruction and loss of life that occurred in New York, much to the relief of élite Bostonians and the city’s African-American community. One feature shared by the riots in Boston and New York was the widespread participation of women and children. The Boston Daily Journal reported that the rioters were ‘composed largely of boys and a good number of Irishwomen’. The war had taken a heavy toll on Boston’s immigrant and working families, who had initially supported the war enthusiastically. The draft riot was community resistance, not only against the war and conscription but also against the local administration, whom many believed ignored home-front deprivations. Wartime inflation and price increases on most staple foods compounded the hardships for families with male relatives in the army. Added to this, a Union private’s pay of $13 a month remained unchanged from August 1861 to July 1864. Soldiers in the Union army endured irregular pay periods, and were often without pay for months. Timothy Regan in the 9th Massachusetts recorded in his diary that the paymaster came at the end of January 1863 and that the men received ‘four months pay of the seven which is due to us’. The temporary loss of income greatly affected immigrant and working-class families. Another concern for Irish families was that their relatives would be wounded in battle. Peter Welsh, who had enlisted in the 28th Massachusetts, prayed that he would not have to return home as an amputee. He had no doubt that ‘the majority of those who get maimed in the war will have but a poor chance to make a living’. The sad homecoming of wounded and disabled veterans was a stark reminder of the grim reality of enlisting. By the summer of 1863, many families in Boston’s Irish neighbourhoods had received word that their relatives had been killed or wounded.

Above: ‘Charge of the police at the Tribune office’: wood engraving from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (1866), depicting the draft riot in New York City, 1863. Similar clashes took place in Boston. (Library of Congress)

The initial outbreak of violence in Boston was directly precipitated by the arrival of draft agents in Irish neighbourhoods. Women and children were disproportionately involved in the riots, which allowed them to enter the debate about the legitimacy of wartime policies. These women, disenfranchised because of their sex, took to the streets to demonstrate their distrust of the leaders of the state and to resist wartime policies that they believed were unfair and undemocratic. Nonetheless, by 27 July 1863 all draft notices had been delivered in Boston. Samuel Bowdlear found it ‘remarkable to see how many of the drafted are refused after examination: the causes are quite remarkable … Many pay up the $300.00. Many substitutes are provided.’ The statistics for the summer draft of 1863 reveal that 32,079 men were drawn in Massachusetts. Of these, 22,343 obtained exemptions and 3,046 failed to report. Of those drafted, 6,690 were obliged to serve. Only 743 offered to serve personally; 2,325 procured substitutes and 3,623 payed the government a total of $1,085,800 to avoid military service. By claiming exemptions and failing to report, many of Boston’s Irish community were able to avoid the draft. As individuals became knowledgeable about the ways to circumvent the draft, direct confrontation with the system declined. For those who took to the streets of Boston on 14 July 1863, however, it was a poor person’s fight against a rich man’s war.

Joe Regan is a history Ph.D graduate of the National University of Ireland, Galway.

FURTHER READING

Samuel G. Bowdlear and Austin C. Wellington correspondence, Boston Public Library.

J.A. Giesberg, ‘“Lawless and unprincipled” women in Boston’s Civil War draft riot’, in J.M. O’Toole & D. Quigley (eds), Boston’s histories: essays in honor of Thomas H. O’Connor (Boston, 2004).

T.H. O’Connor, Civil War Boston: home front and battlefield (Boston, 1997).