The ingenious Mr Edgeworth (1744–1817)

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2017), Volume 25Richard Lovell Edgeworth, born at Bath, Somerset, in 1744, died at Edgeworthstown, Co. Longford, 200 years ago.

By Tony Lyons

The Edgeworths settled in Ireland in the mid-1580s during the reign of Elizabeth I, having come from Edgeware near London. Their principal Irish seat was in County Longford. Over subsequent years the family’s fortunes ebbed and flowed, and were not restored until Richard Edgeworth, Richard Lovell’s father, married the daughter of a wealthy Welsh family.

Above: The Edgeworth Family (with Richard Lovell at the centre) by Adam Buck, 1787. (NPG)

‘Dissipation of every kind’

During Richard Lovell’s youth the family flitted between Ireland and England. The young Edgeworth attended schools at Drogheda and at Edgeworthstown, and at sixteen years of age he entered Trinity College, Dublin, as a gentleman commoner. His short term in Trinity was not filled with any great success or achievements in the academic field: he passed his time ‘in dissipation of every kind’. Just before he entered the university he was involved in a bizarre incident during his eldest sister’s wedding celebrations. One of his friends dressed up as a parson and conducted a mock marriage between young Richard and a young girl with whom he had been dancing. The joke went sour when his father—and the girl’s family—took the event very seriously and had the ‘marriage’ declared void in an ecclesiastical court.

Perhaps such high jinks were a precursor of what was to come. At college he involved himself in all sorts of revelry and debauchery, but after six months he became thoroughly disgusted at the effect of his excessive drinking on his character and habits. It appears that he was permanently cured of his weakness and henceforth became very abstemious, remaining so for the rest of his life. He was not allowed to remain long at Trinity College and his father removed him to Oxford to study; while there, he lived with family friends, the Elers. At Oxford young Edgeworth proved to be a diligent student, and his social life was also filled with anticipation, when he eloped with one of the Elers’ daughters and married her when he was only nineteen. The marriage had limited success, as Edgeworth claimed that his wife had little sympathy with his tastes: she was unimaginative, barely literate, poor in conversation and awkward in company. He repented his folly in marrying her but determined ‘to bear with firmness and temper’ the evil he had brought upon himself.

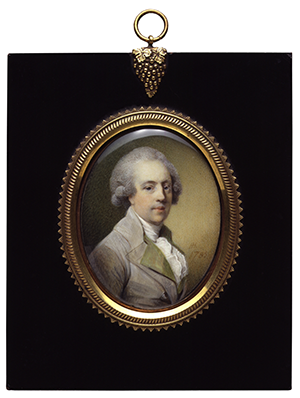

Above: Miniature of Richard Lovell Edgeworth by Horace Hone, 1785. (NPG)

Around this time he began thinking about returning to Edgeworthstown. He became interested, however, in the activities of the Lunar Society of Birmingham and became a very active member amidst a coterie of like-minded individuals who were intent on social, economic and political reform. The Lunar Society was moved by ideas of progress, perfectibility and optimism. The members had broad interests but their major concern was in the sciences, pure and applied, particularly to the problems of industry. While Edgeworth was driven by Lunar pragmatism, he was in many ways an anomaly in the Society. He was neither a business nor a professional man. His estates in Ireland provided him with income sufficient for his needs.

Edgeworth was in close contact with many of the influential thinkers of his day—Erasmus Darwin, Joseph Priestley, Jeremy Bentham, Josiah Wedgewood, William Godwin, Thomas Day, David Hartley, Joseph Lancaster and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He was very aware of rationalist thinkers such as John Locke and the French philosophes of the Enlightenment. He had a wide range of interests, to the extent that he could be described as a polymath: mechanics, steam engines, coach-building, road design (Macadam ‘borrowed’ his blueprint), aerostatics, telegraphy, land reclamation, legal reform, engineering and education.

Richard Lovell Edgeworth was a rationalist and utilitarian. A man of the Enlightenment, imbued with philanthropic enthusiasm, he was to become, in his own lifetime, respected in the English-speaking world as a man ‘ahead of his time’. Historians have cast Edgeworth as merely an eccentric, a dabbler in inventions of gadgets. Upon closer scrutiny, he was much more significant than that. True, he flitted from project to project, never devoting enough time to see any of his endeavours through to a conclusion—we can mention the velocipede, the semaphore, the caterpillar, the door locks, the shelters for haycocks, and the fact that instead of ‘taredgeworth’ we have ‘tarmacadam’ today!

Education

Edgeworth believed in progress and perfectibility: he was an active, observant individual, with a natural turn for experimentation. His concern for education had as its basis the rationalist viewpoint that natural endowment was of little importance. In this he was a follower of John Locke’s tabula rasa theory, whereby individual human beings are born with a blank slate and it is nurture rather than nature that ensures human development.

One of his chief concerns regarding the education of young children was to inculcate in them, through rational means, habits that would lead them to attain a moral way of life. There was an element of ‘once burnt, twice shy’ in his thinking. Like Locke, he was concerned with moulding character: books must present the best examples of virtue. He associated public schools with moral problems whereby pupils might subvert his notion of the moral straitjacket.

Edgeworth could be regarded as a major figure in the history of education. His significance should not be overlooked, especially as he was writing at a time when representatives of tradition, like Knox and William Barrow, favoured the classical curriculum and its aims. It was innovators like Edgeworth who were prepared to try out new ideas. Society was, after all, on the brink of unprecedented industrialisation; education could either be influenced by such changes or stimulate these changes. The political arena was also in turmoil: revolution in France with the demise of the ancien régime and rebellion in Ireland proved challenging for the status quo. Edgeworth was willing to embrace the changes that were taking place all around him.

Non-sectarian

Edgeworth was non-sectarian in his outlook, and at a time in Ireland when sectarianism caused insurmountable difficulties he did not favour the teaching of religion in schools. This view was much in keeping with the increasing concern expressed by successive governments regarding the provision of education in this country. In this respect, he strove to act both publicly and privately to demonstrate the futility of allowing religious bigotry and animosities to cast a cloud over the progress of education in Ireland.

To this end, he established a multi-denominational school at Edgeworthstown in 1816, in the middle of a 50-year debate concerning education provision on a systematic government-backed scale. It was a microcosmic experiment that succeeded for a number of years but fell by the wayside when Lovell, his son, proved to have many shortcomings as a school manager. He fell into financial difficulties and the school had to be bailed out by Maria, Lovell’s sister, who managed to keep it open until 1834. The fundamental school philosophy welcomed all types, Catholic and Protestant, rich and poor. The school was ideologically successful, however: no topics of religious controversy were permitted among the pupils; the school had an ‘excellent’ Protestant rector and a good Catholic priest who lived on the best of terms with each other ‘and who joined in promoting peace and goodwill among all the boys’.

The Commissioners for Education visited the school in 1826. Their report was very favourable: according to Maria Edgeworth, writing in 1839, ‘… they examined and saw the working and playing of the school and had all the opportunities that could be given of observing for themselves and of privately cross-questioning pupils and masters, clergymen and priest’. They found ‘proof of the possibility in practice of what had been deemed by many absolutely impracticable, the educating of Protestant and Catholic children together without injury or inconvenience of any kind’. It is a pity that the school’s success did not lead to the establishment of any other enterprises of a similar nature. Perhaps those who forged the 1831 National School System had the Edgeworthstown school in mind when they adopted an approach to education in which the teaching of religion should not play a part during school hours.

Above: Richard Lovell’s daughter, Maria, the writer. She managed to keep the multi-denominational school that he established in 1816 open until 1834. (Richard Beard)

As an educationist Richard Lovell Edgeworth can be variously classified. He could be called a humanist, a realist, a utilitarian and an empiricist. It is better not to try to label him, however, for labels sometimes stand in the way of understanding. He was too many-sided to fit into a neat classification.

Though he spent considerable time living in England throughout his life, he made Edgeworthstown his permanent home from 1783 until his death in 1817. He was married on four occasions and had 22 children, three of whom died in infancy. He was a practical philosopher whose life displayed high moral standards: he was politically astute and highly principled, refusing a bribe to vote in favour of the Act of Union, and instead voting against it.

His final years witnessed declining health, but he still continued to design new types of machinery for draining the bogs of County Longford. He died at the age of 74 on 13 June 1817 and was laid to rest in the family vault at Edgeworthstown.

Tony Lyons is a former lecturer in Education History at Mary Immaculate College, Limerick.

FURTHER READING

H.J. & H.E. Butler (eds), The Black Book of Edgeworthstown and other Edgeworth memoirs 1585–1817 (London, 1927).

D. Clarke, The ingenious Mr Edgeworth (London, 1965).

T. Lyons, The education work of Richard Lovell Edgeworth, Irish educator and inventor, 1744–1817 (New Jersey, 2003).

P. Murray, Maria Edgeworth: a study of the novelist (Cork, 1971).