In the service of the state

Published in Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 2004), Volume 12 TG: First of all could you tell us about the history of the Mansergh family?

TG: First of all could you tell us about the history of the Mansergh family?

MM: The Manserghs came to Ireland in the seventeenth century, but didn’t come to their present location in Tipperary until the early eighteenth. Originally, three brothers were brought over during the Cromwellian period by their uncle, a Colonel Daniel Redman. From being a loyal officer of Cromwell’s, he seamlessly switched sides to Charles II. The Manserghs married into the Southcote family, settled since 1660 near Tipperary (my third name is Southcote). Originally, the Southcotes let from the Ormonde Butlers, but financial difficulties forced the 2nd duke of Ormonde to sell to his chief tenants. So they started off as tenants, and then became freehold in 1704 and landlords themselves. ‘Minor gentry’ would be the correct term to describe such families. They played very little part in politics, apart from some local functions. There was a high sheriff in Kilkenny in the 1670s. My own great-great-great-grandfather, John Southcote Mansergh, was the high sheriff in Tipperary and returning officer when Sir Robert Peel was first elected for the pocket borough of Cashel in 1809. He had all of 27 electors to look after! His son Richard Martin Southcote Mansergh (my great-great-grandfather) was active on the grand jury, and on various committees—railway compensation, workhouse—and established a national school on his land. He was also chairman of the grand jury in the state trial that found William Smith O’Brien guilty in 1849, where he led a strong plea for mercy.

TG: Moving on to more recent family history, could you tell us a little about your father, the historian Nicholas Mansergh?

MM: He started off as a political scientist, and then moved on to modern history. His most famous book is probably The Irish Question (first published as Ireland in the Age of Reform and Revolution by Allen & Unwin in 1940). He also became a Commonwealth historian, with a particular interest in India. A lot of his work is best summed up in the title of a collection of essays published a few years ago by my mother, Nationalism and Independence (Cork University Press, 1997). While retaining a home in Ireland, my father held academic positions in Oxford and Cambridge and was a British wartime civil servant in the Ministry of Information and the Dominions Office. Both he and his elder brother who stayed in Tipperary not only adjusted to independence but strongly empathised with it, which was unusual given their background.

TG: A unionist background?

MM: Given my family’s lack of political activity (apart from one or two exceptions), I think it can best be described as a background of military service to the British state. There was an assumption that younger sons went into the army or navy. My great-uncle, for example, was drowned in an early submarine accident in 1904 off the Isle of Wight, a vessel of which he was in command. So there was a tradition of state service, that has transferred to an independent Irish state. Of my parents’ five children, three of us are directly or indirectly in Irish state employ.

TG: Your book refers to him as ‘the leading academic exponent of de Valera’s foreign policy’ (of his generation). Could you elaborate?

TG: Your book refers to him as ‘the leading academic exponent of de Valera’s foreign policy’ (of his generation). Could you elaborate?

MM: I was referring particularly to Dev’s idea of ‘external association’, which was revived for the benefit of India in 1949. My father had delivered a lecture in 1948 at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House, saying that the British had made a mistake in not accepting external association for Ireland in 1921–2. One of the civil servants present sent a copy of his lecture to Prime Minister Attlee.

TG: Moving on to your own career, how did you enter the ‘family business’?

MM: I joined the Department of Foreign Affairs in 1974, when Garret FitzGerald was minister. I had six years as a professional diplomat, before being transferred to the Taoiseach’s Office.

TG: That was when Charles Haughey appointed you special advisor on the North?

MM: No, I was appointed later. I became Fianna Fáil Head of Research, when he was in opposition, during the 1981–2 Garret FitzGerald administration. I had to resign from the civil service, which in those days was quite a risky thing to do, and my colleagues were astonished.

TG: What was your brief?

MM: My brief as Special Advisor in 1982 was to pull together policy on Northern Ireland. It was quite a stormy period. The mishandling of the Hunger Strikes had effectively cost Haughey office in 1981, and, when he got back into power for the second time in spring 1982, he found that the British had used the interregnum (the two-month period between the calling of the election and the formation of the new government) to go ahead unilaterally with the Prior Initiative (‘rolling devolution’). So, when Haughey came back into power in March 1982, the situation was not as he had left it in June 1981. Instead of the emphasis being on the Anglo-Irish framework, there was an assertive secretary of state (Jim Prior) who was pulling things back towards an internal settlement. Our first task was to meet an SDLP delegation led by John Hume, who found this totally unacceptable. Then came the Falklands/Malvinas crisis, when Ireland expressed criticism of the British position. I was also involved in discussions with the Irish Independence Party, and out of that came the first notion of what subsequently became the New Ireland Forum, in other words an alternative to the internal initiative.

TG: What attracted you to Fianna Fáil?

MM: I liked its slightly left-of-centre orientation. I approved of the fact that it had a good working relationship with the trade unions. I always disliked Thatcherism in its economic manifestations, and not just its Northern Ireland ones. Also Fianna Fáil was a serious republican party.

TG: What do you mean by that?

MM: I mean that it still seriously pursued the aim, particularly under Charles Haughey’s leadership, of a united Ireland. And thirdly, I preferred its slightly more critical approach to Europe. Fine Gael, on the other hand, was far too Europhile for my taste at that time.

TG: In an address to UCD History Society in 1987, you referred to revisionism as ‘an intellectual fashion of the last 20 years or so, with as yet no adequate counterweight to it’. How do you think things stand now?

MM: Since then, a sort of Hegelian synthesis has been achieved. Traditional nationalist interpretations of Irish history were challenged by revisionism. Both have since been superseded by post-revisionism. The same process is reflected in the Good Friday Agreement — the squaring of circles. The philosophy underlying it is a mixture of the traditional and the revisionist, but it certainly is not solely or mainly revisionist. We have transcended that debate, and I would tend to be happier with the way things are now.

TG: Your point on the Good Friday Agreement would seem to argue that it is political developments that determine how the history is written rather than the other way round. Yet it has been one of the implicit assumptions of revisionism that, if only we could get the writing of history right and the masses of people could imbibe this ‘scientific’ view of history, then their political views would change accordingly.

MM: It is a very complex inter-relationship. It is hard to say how, why, or if one thing leads to another. One of the more interesting differences between the culture of Fianna Fáil and that of Fine Gael under Garret FitzGerald was that, while Garret would count among his major achievements (along with the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement) ‘changing the terms of debate’ on certain issues, the emphasis in Fianna Fáil would be on what had actually been achieved. Often the intellectual ground changes before the political events and political agreements; the latter have to have a sufficient degree of consent and support in the population, so, while politicans also do lead opinion, the ground usually has to be prepared in advance.

TG: Several of the essays in this book are empathic with the Anglo-Irish tradition. How do you respond to the criticism voiced in recent newspaper correspondence between yourself and Jack Lane and Brendan Clifford of the Aubane Historical Society that this tradition, 1798 and the United Irishmen excepted, has contributed little or nothing to the emergence to the modern Irish nation?

MM: Empathic perhaps, but I’m also highly critical of the Anglo-Irish tradition, as indeed my father was; southern unionism played its cards very badly. There were always three choices for Irish unionism in the past — and for Ulster unionism today. The first was to maintain the ascendancy for as long as they could. The problem arises when that is no longer tenable; do they retreat without engagement or do they engage? My criticism of southern unionism — with certain important exceptions like Parnell — was that it retreated without engagement, until the Irish Convention of 1917–‘18 when it was too late. I am more encouraged in relation to the North at present, since in the end Trimble unionism did engage, although I would be critical of the level of engagement. Even Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party have engaged; they are talking to the Irish government. There are of course voices within unionism who would like to retreat behind the Westminster bastion without engagement, the McCartney/Burnside strand of thought.

In relation to the controversy with Lane and Clifford, nation and state are not coterminous; you do not have to be a nationalist to be Irish, and indeed, as the Good Friday Agreement has very clearly said, there is no incompatibility between unionism and Irish nationality. I don’t subscribe to the ‘two-nations theory’. What they are engaging in, denying the Irishness of all the major cultural figures of Anglo-Ireland — Swift, Berkeley, through to Elizabeth Bowen — saying essentially that they were English, that is not the view of the state, nor is it the view of most people. As Fintan O’Toole effectively pointed out in the Irish Times, you would be ripping out most of the cultural endeavour pre-independence or pre-1900. A lot of our towns and villages, cities even, were laid out by people from that tradition. Then there are the scientists: Boyle, Hamilton, Parsons, etc. Of course, they were a privileged class, and they also had a very negative effect, not just in terms of the landlord system but in their support for the British connection when it was threatened. That delayed independence by the best part of two hundred years. So I have no sentimental illusions about the Anglo-Irish. But if one is interested — and the two-nation theorists may not be, I don’t know — in this country coming together, the whole island that is, some time in the future, you simply cannot afford to write off a small but important minority tradition, as that will be extrapolated and writ large by unionists as their likely fate too. Some of those attitudes are pretty destructive, and a lot of them appeal to prejudices that were understandable and more current 50, 60 years ago. The nation is not to be understood in purely nationalist terms. Even the state has to be inclusive and embrace other traditions. One of them wrote that in 1922 the Anglo-Irish were left high and dry. In a political sense, that is largely true. But what choice was there for those who wanted to remain? It was to become Irish on the same terms and on the same basis as everyone else, and what was wrong with that? It did not leave them ‘high and dry’, unless they chose to be marooned. I have taken a more positive, though not totally uncritical, view of Elizabeth Bowen. My feeling is that she has been chosen as a plausible example to prove the theory.

TG: You were closely involved with the then government’s 1798 National Commemoration Committee. What was its objective, and was it achieved?

MM: Its objective was to commemorate in a dignified and constructive manner very difficult events of two hundred years previously. It was remarkably successful in that people were able to express pride in their community all over the country in a way that was not divisive. Commemoration is a slightly different exercise from pure history writing. Commemoration involves studying and taking a fresh look at the past, but also relating its relevance to the present, perhaps in a more explicit way than one might necessarily do in pure history writing, which is to a large extent treating events and people in the past on their own terms rather than in the terms of the present. Commemoration is a hybrid, not a pure academic exercise. It is making history popular. But perhaps there was too great a shift from an over-sectarian interpretation of 1798 to one where that element of it was excessively underplayed, I would make that observation. And searching questions have been asked about what degree of reality the ‘Wexford Republic’ had. But at the same time, if you read contemporaries like Myles Byrne, he puts tremendous emphasis on the joint Protestant/Catholic leadership. I find the whole period of the United Irishmen, and especially the early ‘90s constitutional phase, an interesting, inspiring one.

TG: How do you respond to criticisms of the commemoration by academic historians like Roy Foster or Tom Dunne?

MM: Roy Foster adopts a supercilious attitude to commemoration, as if, because it is an ‘impure’ exercise, it shouldn’t be undertaken at all. The reality is that people, whether historians or governments like it or not, are going to commemorate the events of the past. Governments can decide to get involved or they can keep their distance, and if they keep their distance they must not be surprised if things go in directions that they do not necessarily like. I would be entirely unapologetic about the Famine, 1798, and Emmet national commemorations; they were very worthwhile exercises, and they stimulated an enormous amount of historical publication and debate.

TG: One of Tom Dunne’s criticisms was that the 1798 commemoration in particular became a sort of a propaganda adjunct of the Peace Process and of the Good Friday Agreement in particular. How would you respond to that?

MM: Since I think the Peace Process and the Good Friday Agreement are thoroughly good things I wouldn’t have a problem with that. After all, were not some of the revisionist historians writing things in certain ways, because they didn’t want to give the slightest comfort to the Provisionals? So, if one is being criticised by pure, unideological historians, who never think about the present when they write history, that’s fine.

TG: Some of the essays in this book are speeches you delivered at commemorations of various anti-Treaty Republicans like Liam Lynch, for example. One reviewer expressed surprise at this, in that it implied retrospective endorsement of the violence of the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War.

MM: It didn’t. My attitude to the period is that the Republican side had a very good political case. There were three parties to the conflict — the Free State, the Republicans and the British — and I would be quite critical of all three. The Civil War in all probability would not have happened but for intense British pressure; it was Churchill at his worst. But I think mistakes were made on both Irish sides. At the end of the Treaty debate, de Valera and Brugha gave assurances that the military would stay under political control. They didn’t, and the politicians were completely sidelined and had to trail behind. So, if you read my speeches carefully, they are not an endorsement of the Republican military struggle in the Civil War. But the Republicans had a political case, and what they should have done, and what Fianna Fáil did subsequently, was to fight the Treaty politically.

TG: Do you have a favourite personality from Irish history and why?

MM: Parnell would be strong favourite. I have come to admire William Drennan, whom I regard as the father of constitutional republicanism, someone I discovered relatively late in life. I would have a strong empathy with de Valera, as did my father. After all, both de Valera and Parnell were ‘the chief’. De Valera was the principal state-builder post-independence, but there is a tendency to forget the very important role he played between 1917 and 1921. He was the voice of the movement, and he articulated the political case very well. There was a tripartite leadership between himself, Collins and Griffith, and they were all important in their different ways. But Dev was also inspiring in that period. And then there were the enormous skills required to maintain neutrality and independence during World War II.

TG: What would you say of the view, though, that that was when he should have retired, after the war, that he hung on for a decade too long?

MM: There’s no doubt that Ireland lost ground in the late ’40s, early ’50s. Progress was made, but relatively we fell back vis-à-vis other European countries. They had to be more radical in their reconstruction, because they were seriously damaged in the war in a way that we weren’t, and that maybe gave an impetus to their economies. We were quite slow in getting our act together post-war, and deciding in what direction we were going to go. But would Seán Lemass necessarily have come out on top long before 1959? It can’t be taken for granted; he had opposition within the party. All the people mentioned had faults and flaws, and I wouldn’t totally idolise any of them, but de Valera had an intellectual grasp and rigour that was unique.

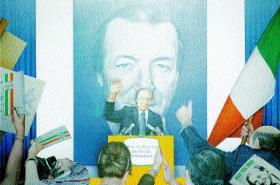

Robert Ballagh’s The Decade of Endeavour: Portrait of Charles Haughey—‘his reputation has fallen but his achievements remain’. (Private collection)

TG: How do you think history will judge the man who first appointed you as special advisor on Northern Ireland, Charles J. Haughey?

MM: In one sentence, applied by a correspondent in Le Monde in 2000 to François Mitterrand: ‘his reputation has fallen, but his achievements remain’ — in Haughey’s case, the dramatic economic recovery post-1987 from which we have never looked back; the International Financial Services Centre; Temple Bar; the free schemes for social welfare; his patronage of the arts.

TG: How crucial was he in the early stages of the Peace Process?

MM: He established the network of contacts. He was involved in the earliest drafts of what subsequently, and somewhat misleadingly, became known as the ‘Hume–Adams’ document and later in much amplified form the Downing Street Declaration. Over his last five years in office he had a tremendous grasp of the levers of power. Senior civil servants from many departments would have had great respect for the way he conducted business. I suppose the 1990 European Union Presidency was probably the summit of his political career and that was a very important period — German unification, the ending of apartheid, the Velvet Revolution, etc. He was a person of immense ability, but also flawed — like a lot of major historical figures. It would be quite impossible to write the history of the second half of the twentieth-century Irish state without reference to him. He cannot be written out of history.

Tommy Graham is editor of History Ireland.