In defence of modernity—the Ulster Solemn League and Covenant, 1912–14

Published in Editorial, Issue 3 (May/June 2014), Volume 22

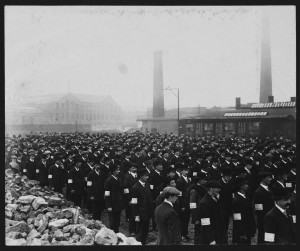

Ranks of Belfast factory workers with UVF armbands. The fact that the labour movement in Britain was seen as pro-Home Rule made it impossible for Belfast labour to win the confidence of the Protestant working class. (PRONI)

The Francis Hutcheson Institute is a ‘think-tank made up of academic, political and former security personnel who combine their knowledge and expertise to develop and deliver . . . analysis of contemporary conflict situations and related economic, political and social problems around the globe’.

This reporter travelled from Dublin with lots of baggage. Rather than a ‘defence of modernity’, the Ulster Covenant could be regarded as part of a reactionary rebellion directed at undermining the democratic decision of the UK parliament relating to the third Home Rule bill. Those who signed the Covenant pledged ‘by all means necessary’ to resist Home Rule. Was this an implicit threat of armed rebellion, made explicit by the illegal and subversive Larne gunrunning? Was the Curragh mutiny a brazen example of the military élite siding with the Tory minority to defeat the democratically elected government of the day? The Home Rule aspirations of three quarters of the population of Ireland were set at naught.

The eminent historians who addressed the seminar had more nuanced approaches. Dr James Dingley surprised his mostly unionist audience by suggesting that Ulster unionism is a nationalist ideology. Unionist nationalism differs from Irish nationalism in fundamental ways, however. According to Dr Dingley, unionist nationalism has its roots in the Enlightenment and ideas of religious dissent, reason, science, progress and industry. Irish nationalism is romantic, rural, traditional and of course Roman Catholic. And at the time of the Home Rule crisis southern Ireland was a small-proprietor farming economy under immense pressure from foreign competition. The foreign produce strang-ling Irish agriculture was moving around the globe in large ships built in Belfast. It was natural in the economic circumstances that these contending nationalisms would collide.

Professor Graham Walker is not a unionist historian, as he was recently described by Eamon Dunphy, but a historian of unionism. He contended that, while the great propaganda coup of the Covenant was a pan-Protestant endeavour, the Presbyterian community was particularly cohesive and purposeful in the campaign. T.G. Hueston declared that the campaign against Home Rule was guided ‘not by a jingo spirit but by a martyr spirit’ and was being fought by those who had ‘fought battles for their RC fellow countrymen when they really were downtrodden’.

Professor Henry Patterson suggested that at the time of the crisis Belfast had a well-developed labour movement with a close relationship with the movement in Britain. Significant socialist parties were emerging in other parts of Europe but not in the north-east of Ireland. The problem was the opposing positions on the Union within the working classes. The virulent sectarianism that resulted in hundreds of Catholics and some socialist Protestants being expelled from the shipyards in 1912 was not the main problem for labour. The fact that the labour movement in Britain was seen as pro-Home Rule made it impossible for Belfast labour to win the confidence of the Protestant working class.

Professor Paul Bew reviewed the political and economic arguments against Home Rule. The Liberal government had attempted to foist Home Rule on Ulster to buy the support of John Redmond’s Nationalists. They had not told the British electorate that ‘they were about to throw one million citizens out of the United Kingdom against their will’. The Liberals had no democratic mandate. The Unionist leaders, however, imported guns. These guns were never used or even produced in public. The Unionist leadership believed that whoever struck the first blow would lose. If those guns were ever to be used, it could only have been in a dirty war against Catholics. Fair-minded unionists must acknowledge that those who brought guns to Larne introduced the gun into Irish politics.

Professor Greta Jones reviewed how a debate within the Irish scientific community on either side of the Home Rule crisis had implications for the future of science in an independent Ireland. Irish scientists influenced by Darwinism and by Thomas Huxley fought a battle for scientific freedom within Irish universities. Their opponents were the Roman Catholic hierarchy. In the Free State after independence the hierarchy emerged winners. Professor Jones did not say so but it seems like a case of Home Rule being Rome Rule.

During the plenary debate younger members of the audience spoke of the emerging identity of ‘Northern Irish’ as opposed to traditional labels of British or Irish. Professor Patterson thought this the road to nowhere. The institutions that emerged after the Good Friday Agreement are tribal rather than nationalist, however. The young people’s attempts to transcend past division are an exercise in modernity of which Francis Hutcheson would likely have approved.

Fergus Whelan is the author of Dissent into treason: Unitarians, king-killers and the Society of United Irishmen (Brandon Books, 2010)