Illuminated Address to Charles Stewart Parnell from the Tenant Farmers of Ireland, 1880

Published in

18th–19th - Century History,

Features,

Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2011),

Parnell & his Party,

Volume 19

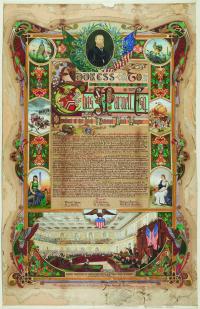

were a standard feature of late nineteenth-century Irish nationalism and were generally presented by voluntary subscription in recognition of outstanding achievement. The National Library of Ireland is the custodian of a large collection of such addresses, one of the most remarkable of which is the ‘Illuminated Address to Charles Stewart Parnell from the Tenant Farmers of Ireland, 1880’. The parchment was presented to Parnell by the leadership of the Land League to commemorate the occasion of his address to the United States’ House of Representatives in February 1880. The manuscript was painted and designed by Thomas Lynch of Dublin, who specialised in illuminated addresses, and is heavily influenced by the motifs and emblems of the Celtic revival.

were a standard feature of late nineteenth-century Irish nationalism and were generally presented by voluntary subscription in recognition of outstanding achievement. The National Library of Ireland is the custodian of a large collection of such addresses, one of the most remarkable of which is the ‘Illuminated Address to Charles Stewart Parnell from the Tenant Farmers of Ireland, 1880’. The parchment was presented to Parnell by the leadership of the Land League to commemorate the occasion of his address to the United States’ House of Representatives in February 1880. The manuscript was painted and designed by Thomas Lynch of Dublin, who specialised in illuminated addresses, and is heavily influenced by the motifs and emblems of the Celtic revival.

An impending famine in the west of Ireland threatened to dwarf Ireland’s political considerations in 1879, and the urgent need for a coordinated response to the crisis led to the formation of the Land League by the indefatigable Michael Davitt, funded by financial support from Clan na Gael, with Parnell as the movement’s titular head. The Land War of 1879–82 was the greatest mass movement in modern Irish history and was responsible for the creation of elaborate and enduring systems for the waging of moral and economic warfare by the rural poor. The use of boycott against those who were seen to be oppressing the poor, the functioning of land courts, the use of embargos on evicted farms and the turning of evictions into scenes of mass demonstrations represented a sustained challenge to the state’s control of the Irish countryside. The Land War became the fundamental catalyst for convincing the British political establishment of the indefensibility of the land tenure system in Ireland and, on a more profound level, created a realisation amongst Irish people of the inherent vulnerability of British power in Ireland in the face of a resolute and united people.

The Land League harnessed the respectability of Irish representatives at Westminster, the sheer mass of numbers of the rural poor, and the organisational skills of the physical-force tradition at home and in the US. An upper-class Protestant landlord, Parnell had been sympathetic to Fenianism from an early age and, though regarded as a wretched public speaker, decidedly nervous and speaking with a pronounced upper-class English accent, he spoke to enthusiastic Irish-American audiences in 62 cities during his four-month tour of the United States. With the threat of eviction hanging over tens of thousands of families at home in the west of Ireland, Parnell addressed a specially convened evening session of the House of Representatives, with his mother, an American heiress, and his sisters seated by special dispensation in the chamber. The leader of Irish nationalism spoke without notes and appealed for support for Ireland directly from the floor, rather than from the speaker’s chair, as depicted by Lynch. While the occasion was well received by Irish-Americans, only a small minority of representatives actually attended the session, and the packed house depicted by Lynch is inaccurate.

The address captures the essence of a formative moment in modern Irish nationalism, however, represented by the fusion of conservative nationalism at home and radical separatism in the United States into a new political alliance. With the Home Rule League virtually defunct in Ireland by late 1878, and with little to be hoped for from an increasingly fractious Irish Parliamentary Party at Westminster, Parnell had become convinced of the political benefits of an alliance with the Fenian Clan na Gael movement in the US. The ‘new departure’ was given an immediate impetus by the disastrous harvest of 1879, which threatened imminent famine for vast numbers of the rural poor in the west of Ireland. The wording of the address reflects the contemporary anger and resolve in rural Ireland that ‘the fate which befell our famine slaughtered kindred’, ‘through the operation of an infamous land system’ by ‘felonious landlordism’, would never be repeated.

The late nineteenth century in Ireland saw a profound artistic reawakening of interest in Gaelic history, culture and art, and the Celtic designs employed by Lynch reflect standard imagery of the period, with edges of Celtic interlace, the use of cross patterns and the employment of zoomorphic symbolism, originating in fifth- to ninth-century Irish monastic art and rediscovered in the late nineteenth century as popular symbols of an ancient nation, new in its aspirations and resolve. The use of the shamrock, round towers, harps, wolfhounds and Gaelic maidens originated during this period, but Lynch’s employment of industrial furnaces blazing on the horizon in the bottom right-hand corner is far less typical of the genre. The text of the address places Ireland’s ‘poverty and humiliation’ within an international context, and the achievement of ‘the landlord banished portion of our people’ vowing for Ireland’s deliverance in ‘that Mighty Western Republic’ represented a recognition of the shared heritage of both nations and a direct appeal to Irish-Americans for their support. The clash of two civilisations—the Gall versus the Gael—infused popular motifs, and the lack of sophistication in some of the symbolism, such as the soldiers in the top corners, reflected art’s inherent function in resurrecting a unique sense of identity amongst a defeated people. Lynch’s use of images of the Great Famine was unusual, however, and reflected the importance of emigration and the role of the Irish diaspora to the success of the ‘new departure’ itself. The lack of folk history surrounding the Famine reflected the psychological trauma, shame and incomprehension that the tragedy evinced in later generations, and the significance of Lynch’s eviction scene would have been readily apparent.

The Parnell address is currently being conserved by the National Library, but a high-resolution image (and hundreds of others) can be viewed at www.flickr.com/photos/nlireland. Sign up to the Library’s Facebook site to receive automatic notification of all Library events, exhibitions and on-line resources. HI

were a standard feature of late nineteenth-century Irish nationalism and were generally presented by voluntary subscription in recognition of outstanding achievement. The National Library of Ireland is the custodian of a large collection of such addresses, one of the most remarkable of which is the ‘Illuminated Address to Charles Stewart Parnell from the Tenant Farmers of Ireland, 1880’. The parchment was presented to Parnell by the leadership of the Land League to commemorate the occasion of his address to the United States’ House of Representatives in February 1880. The manuscript was painted and designed by Thomas Lynch of Dublin, who specialised in illuminated addresses, and is heavily influenced by the motifs and emblems of the Celtic revival.

were a standard feature of late nineteenth-century Irish nationalism and were generally presented by voluntary subscription in recognition of outstanding achievement. The National Library of Ireland is the custodian of a large collection of such addresses, one of the most remarkable of which is the ‘Illuminated Address to Charles Stewart Parnell from the Tenant Farmers of Ireland, 1880’. The parchment was presented to Parnell by the leadership of the Land League to commemorate the occasion of his address to the United States’ House of Representatives in February 1880. The manuscript was painted and designed by Thomas Lynch of Dublin, who specialised in illuminated addresses, and is heavily influenced by the motifs and emblems of the Celtic revival.