Hurling in Thurles and district before the GAA

Published in Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2020), Volume 28One form tended to be rough and sometimes led to serious injury.

By J.M. Tobin

When thirteen men gathered in Hayes’s Hotel, Thurles, on Saturday 1 November 1884 to establish the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), few could have envisaged the impact that their initiative would have on Irish sport, not least on the game of hurling. The GAA saved hurling from extinction and provided it with a new structure for a changing world. But what was the nature of the game in the pre-codified age?

Formerly both a field and a cross-country game

Writing in 1602, Richard Carew described the Cornish game of hurling, which, incidentally, bore similarities to modern-day rugby football: ‘Hurling taketh his denomination from throwing of the ball, and is of two sorts, in the east parts of Cornwall to goals, and in the west to the country’. Intriguingly, prior to the founding of the GAA, the stick-and-ball game of hurling that was played in Ireland was also of two distinct types: one a field game similar to the modern version and the other a largely unstructured, cross-country contest, known in Tipperary as ‘hurling home’ and in parts of Munster as ‘scoobeen’.

The former game was played within a clearly defined area, such as a field or green, between opposite goals. The goal could be an arch of willow, a gap in a wall or hedgerow, a corner of a field or, in fact, an entire wall or hedgerow. Teams were of equal number and could comprise sixteen, 21, 25, 27 or 30 players. Goalkeepers were not used, and participants were divided into three groups: backs, midfielders and forwards. A goal was the only score permitted, which, depending on customary practice or the period in question, was obtained in one of four main ways. The ball could be driven (i) under a bow of willow, (ii) through a narrow gap, (iii) into a corner of a field or (iv) against a hedge or wall. In general, the outcome of a game was decided by the first score. Return challenges were not uncommon, however, and in those instances victory was awarded to the team with the best winning record from a series of three meetings.

Hurling home usually began at the boundary between two counties, parishes or townlands. It occasionally featured as many as 500 players on each side, and the aim was to bring the ball back to a landmark in one’s own territory. Not surprisingly, hurling home tended to be rough and sometimes led to serious injury.

Hurling in Thurles and district

When Edward Wakefield visited Tipperary at the beginning of the nineteenth century he was greatly impressed by the athleticism of its inhabitants, observing that they ran, jumped and played hurling without shoes or stockings. The game and its lore were especially popular in the Thurles district.

Those from Moycarkey-Borris were familiar with the match held c. 1800 at Urlingford, where a Tipperary selection, comprising players from their parish, along with others from Gortnahoe and Glengoole, defeated Kilkenny. The victors on that occasion, aided by their womenfolk, won the ensuing fight and were known thenceforth as ‘the Tipperary stone-throwers’. They would have listened also to old people speak of the hurling home when the ball was brought from Kilkenny to the castle at Moycarkey. Turtulla natives were familiar with the Nicholson family of Turtulla House (now the clubhouse of Thurles Golf Club) and their team of hurlers, composed of tenants, workers and neighbours, which played against sides sponsored by other members of the landed gentry. There were memories, too, of the match played at Galbertstown, near Holycross, on 25 July 1769, involving ‘three baronies against all Ireland for 100 guineas a side, play or pay’. And on the outskirts of Thurles at Brittas, just a short walk through Pudding Lane, there had been an encounter ‘betwixt Upper and Lower Ormond boys, and those of Thurles and Kilnamanhery’, on 1 September 1770. The game was played ‘on a delightful green properly corded and cleared’, and was followed by ‘an elegant assembly’ in the town that evening, ‘for which the best music [was] engaged … to render [it] pleasing to the ladies’. Others were bearers of an older but nonetheless enduring tradition linking the aristocratic Mathew and Purcell families of Thurles and Loughmore to the patronage of hurling in their respective localities.

Patrick Fanning

All of the foregoing accounts refer to adult hurling. On the other hand, very little is known of the juvenile game, except for the occasional reference. The Young Ireland leader Michael Doheny (1806–63), who received part of his education in Thurles, recalled in his memoirs the hurling matches he played as a boy in his native Fethard.

Fortunately, a reference also exists linking a pupil of Thurles CBS to the game. A journalist recording the reminiscences of Patrick Fanning (1831–1916), a Main Street resident, wrote:

‘Mr Fanning says he was a boy of 13 years of age attending the Christian Brothers’ schools when Smith O’Brien was arrested at Thurles railway station … [Saturday 5 August] 1848. Mr Fanning and some other boys were hurling in a field by the side of the station when the ball was driven in on the platform. The station premises he says were very different then from what they are now and there were only two or three buildings there altogether. He and another boy went after the ball, and just as they reached the near platform from the town side the train from Dublin arrived … Mr Fanning explains … “There was one gentleman behind my back, and I didn’t know who he was … until I heard the guard say: ‘You’re Smith O’Brien, and I arrest you in the queen’s name’.” … Mr Fanning goes on to describe the sensational arrest of the great revolutionary leader, and how the streets were soon lined with military, and [how] Smith O’Brien was escorted to the soldiers’ quarters, where Mr Kirwan’s stores now stand in New Street [Parnell Street].’

Aftermath of the Famine

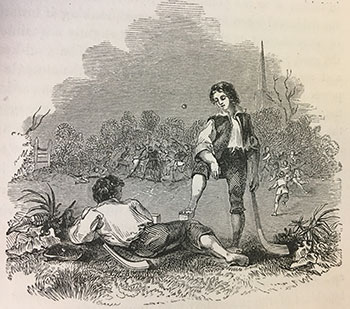

Above: A hurling match, c. 1840. Note the slender profile of the hurleys, the relatively large ball and the narrow, unmanned, goal in the corner of the playing area.

Hurling survived the dislocation of the Famine years and continued to be played in the hinterland of Thurles until at least the 1860s. For example, John Ryan and Edmund Hackett were bound to the peace at the assizes for the manslaughter of John Ryan at a game in Two-Mile-Borris on Sunday 14 September 1862. While at the Horse and Jockey, young John Manning of Ballymurreen, who was born in 1857, saw men play hurling from ‘ditch to ditch’. The ditch-to-ditch style was also popular about that time in both Templetuohy and Tubberadora, as recalled by Ned Davy and Mike Ryan respectively. Hurling homes also remained in vogue. Fr Philip Fogarty, the GAA historian, recorded in his notebook that one of the Quinlans of Forgestown, Horse and Jockey, had been involved in one such encounter. Fogarty was also aware of a hurling home between Leugh and Rahealty, two townlands in Thurles parish. The captains on that occasion were Callanan and Flynn respectively. The ball was thrown up in Cassestown and ‘the field of action’ was from the hill of Leugh on one side to the castle of Rahealty on the other. Similarly, Jack Maher of Glenreigh, Holycross, heard of pre-1884 cross-country contests between Holycross and Moycarkey. The meeting place was Paddy Maher’s three-cornered field, on the road from the village to the Yellow Lough, which was then on the boundary between the two parishes. Jim Hayes of Holycross village also heard of those clashes. His uncle Willie had been a participant on one occasion but was obliged to use a ‘crook’, as there was not a hurley available.

Conclusion

It was not surprising, therefore, that teams from traditional strongholds such as Thurles, Two-Mile-Borris, Tubberadora, Moycarkey and Holycross would feature prominently on the fixture lists of the Tipperary hurling championship in the early GAA era. Moreover, it was a Thurles combination, augmented by some others from outlying parishes, that brought back the inaugural national title of 1887 to Tipperary. Although the codification process had changed hurling irrevocably, it would appear that a significant number of the game’s practitioners continued to draw inspiration from a residual sporting culture.

J.M. Tobin is a Thurles-based sports historian.

FURTHER READING

J. Chynoweth, N. Orme & A. Walsham (eds), The Survey of Cornwall by Richard Carew (Exeter, 2004).

P. Fogarty, Tipperary’s GAA story (Thurles, 1960).

L.P. Ó Caithnia, Scéal na hIomána: Ó Thosach Ama go 1884 (Dublin, 1980).

K. Whelan, ‘The geography of hurling’, History Ireland 1 (1) (1993).