Languedoc in Laois: The Huguenots of Portarlington (3:1)

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 1 (Spring 1995), Volume 3John S. Powell

It was a sure sign that the Huguenot plantation of Portarlington in County Laois was dead when a historian turned it into an article (Sir Erasmus Borrowes in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology in 1855). Previously the town had seemed a curiosity of the Irish midlands, a hangover from seventeenth-century religious wars.

It was a sure sign that the Huguenot plantation of Portarlington in County Laois was dead when a historian turned it into an article (Sir Erasmus Borrowes in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology in 1855). Previously the town had seemed a curiosity of the Irish midlands, a hangover from seventeenth-century religious wars.

Since then the Huguenots have gone from good to better with a very high reputation, very different from any other immigrant group in Britain or Ireland. Indeed in the popular imagination it seems that every Huguenot was either a master weaver or a silversmith, skilled in the arts of France, and a blessing to which ever place they put down roots. This evocation of the Huguenots in the second half of the nineteenth century was due to writers like Samuel Smiles, whose book on the Huguenots went into seven editions between 1867 and 1894, David Agnew with his Protestant Exiles from France in 1866, plus the contributors and researchers of the Huguenot Society of London founded in 1885. The Huguenots were safe and useful examples in a period when English Protestantism was loosing its certainties in the present. In 1914 Peter Guilday wrote a history of English Catholic refugees in France, claiming ‘we have grown so accustomed to eulogies of Huguenot exiles’.

The Huguenot history of Portarlington is worth pursuing beyond the rosy glow put on it in the nineteenth century. Of the assertions made at that time, one is worth repeating, namely that for about fifty years there was a French-speaking town by the Bog of Allen, and that of all the Huguenot communities, Portarlington was the one where the French outnumbered all others, and integration came correspondingly later.

The scene of battle- a commonplace experience for nearly all of Portarlington’s Huguenots.

Lord Arlington

The town itself is not very old. It was the creation of Henry Bennett, Lord Arlington, in 1666 from lands seized from the O’Dempseys for their part in the Kilkenny Confederacy and not fully returned under the Act of Settlement. Some of the O’Dempseys fled to France and settled near Compiègne under the name of Odempse, thus predating Portarlington’s French connection by some forty years. Surrounding older settlements including the Norman castle of Lea which had guarded the Barrow crossing into the Pale, were subordinated to this new Protestant plantation.

Henri de Massue de Ruvigny,Earl of Galway – detail

(Courtesy of The owner)

It was given borough status like many other towns in the area and with its two MPs provided the landlord of the day with a voice in parliament. Lord Arlington was a member of Charles II’s cabal of ministers but in 1685 he sold all to Sir Patrick Trant. The town had not been a success in human or financial terms, and as Trant was a Jacobite his property was seized and confiscated in 1692.

de Ruvigny

The Huguenot presence was fortuitous. Henri Massue Marquis de Ruvigny had been the last Huguenot representative at the court of Versailles before the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 which effectively outlawed any expression of Protestantism in France. His was a sedate exodus, unlike many of Portarlington’s settlers, such as Madame de Champagné who, with her children, got away from La Rochelle hidden in wine casks bound for Falmouth. Her husband took a land route through Paris to Rotterdam which was already congested with refugees. De Ruvigny was allowed to retain his French property for income as long as he did not engage in military activities. This condition he and his brother broke, as they fought in the army of William of Orange in Ireland. Specific Huguenot regiments were created, and well known is the story of Schomberg shouting to his troops at the Boyne to see their Catholic countrymen in the army of James II and look on them as the real enemies, ‘Voilà vos persecuteurs!’ De Ruvigny fought at Aughrim, became ennobled as Lord Galway and in 1697 was appointed one of the Irish Lord Justices.

Military settlement

William of Orange gave de Ruvigny the Portarlington estate as a gift for war services. It cannot be judged whether de Ruvigny chose the role or was pushed into it, but the town became a centre for the settlement of retired soldiers and their families from these regiments. From 1692 to 1702 Huguenot soldiers came and went. Whatever occupations they had had in France, the military became a permanent life for many families. A high number were officers, and from the minor nobility of southern and western France. In many cases their title in France became their surname in Ireland. The Robillards were Sieurs de Champagné near La Rochelle, and in Ireland became known as Champagné. This image was puffed up by Borrowes who wrote:

The exiles formed a highly select society…of pure morals, and of gentle birth and manners. They were contented, cheerful and even gay. Traditions still exist of military refugees in their scarlet cloaks in groups under the old oaks in the market place, sipping tea out of their small china cups…

It is an enticing picture, augmented by reports of gardens, orchards, and families conversing in French living in houses of French style, and the Irish kept very much out. Only two or three of the settlers were rich enough to plan fine gardens and houses, and they did seek to maintain their Frenchness, but this experience was not shared by all. For many the military cloaks were probably sold, and instead of old battles talked over, it would be the dire consequences of late payment of pensions. There was no tea for Jean de Chizadour, an ensign in Belcastel’s regiment on a pension of one shilling and sixpence and ‘une très mauvaise cabine’. Several times the church had to step in with financial aid when pensions were delayed.

Housing was a problem. De Ruvigny financed—he had to—the erection of between 130 and 150 dwellings, and he established two schools, one for the French children and one for the English who had remained from Lord Arlington’s plantation. Then disaster struck.

Dean Arthur Champagne of Kildare(1714-1800), a man of many livings,and son of the family who fled La Rochelle in 1987. (Courtesy of The owner)

Act of Resumption

The gift of the land by William of Orange had been resented by parliament in London which sought all confiscated Irish land as a means of financing his wars. An Act of Resumption deprived de Ruvigny of his estate and threw into doubt all the leases he had granted. In fact there was equivocation over the Huguenots in Ireland. At first they were seen as foreigners taking land and capital, a drain on the English government, but their Protestantism, albeit non-Anglican at this stage, useful as a garrison class over the Irish, finally saved them. While pamphleteers wrote scathingly of King William who preferred Huguenots and Dutch, others wrote that ‘the French Protestants have many men of letters among them… ‘Tis not to be doubted that they, living…among the ruder Irish, will in time greatly help to improve them both in manners and religion’. By 1702 the Huguenots in Portarlington were saved, their leases were acknowledged, and in effect the Huguenot plantation was secured at a time when plantation in Ireland was no longer seen as necessary.

Church registers

In 1694 a church was established ‘à la forme ancienne de nos églises de France’, in other words Calvinist, and by a series of good fortunes the registers, written in French until 1816, have survived. These registers form the main source of information about the French town. They reveal places of origin in France, occupations both military and civil, and some of the dramas behind birth and death. Abraham Charles Courteille was born prematurely in December 1696 after an accident befell his mother at home. The father immediately set off to find the pasteur and ask for a home baptism ‘ne pouvant êtré transporter sans exposer sa vie au danger de la luy faire perdre’. The baptism was performed but the baby died eight days later. His body went to the cemetery in Lea, ‘dont l’âme etant allée à dieu’.

Conformity

In the church Pasteur Benjamin de Daillon celebrated his liturgy. Before his escape from France he had been on the run, imprisoned once in the Conciergerie de Paris, saying his services in secret rooms, hiding in the hills. Now the local Catholic clergy were condemed to a similar predicament but fate had a final twist in store for de Daillon. In 1702 as part of the Act recognising de Ruvigny’s leases, control of revenue was vested with Bishop Moreton of Kildare, and he insisted that de Daillon be re-ordained and follow the rites of the Church of Ireland. The Huguenot Calvinists throughout Ireland proved much easier to bring into conformity than the Scots. De Daillon, though, would not have it, and left with a small following of mostly the non-noble population.

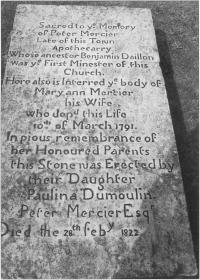

Grave of Peter Mercier in Portarlington.

A French town?

The Frenchness of Huguenot Portarlington is a matter of debate. As with the German Palatines in County Limerick, French language and culture slipped away after the first generation, only to be retained as a badge of identity for formal occasions. Many writers have mistaken this formal usage for a living language, and what may have died in the vernacular in the 1730s lived on in honoured moments until the 1820s. The second generation of Champagnés had to get help with their written French from old Pasteur Caillard. The town clerk, Micheau, wrote in English at corporation meetings but across the road in the vestry accounts used French. Taking the Anglican rites assisted this integration, and often the richer families of French Portarlington had gone by the fourth and fifth generation to good marriages and careers elsewhere.

In 1750 John Wesley preached in English to the townspeople but saw a stilted French service in the church. In 1795 Count Joseph Boruwlaski, better known as the Polish Dwarf, whose income was from his height of thirty-eight inches and pianoforte recitals at concerts, toured Ireland and was genuinely surprised to find a French connection. With an eye to his patrons he claimed that he felt himself to be in the middle of France by the charm and civility shown him. Government commissioners, however, who came to Portarlington in 1831 to mark its parliamentary constituency—where only fifteen men had the vote—noted that apart from a few surnames the refugee families ‘are now scarcely to be distinguished from the other inhabitants’. The one surviving French gravestone is a deliberate anachronism of 1804 sculpted for Antoine Fleury, descendant of Waterford Huguenots, who was a curate nearby.

The economy of Portarlington was not sound. A dependency on military pensions for an elderly population did not auger well, and in retrospect it seems that, however refined and genteel some of them were, an almost ‘poor white’ attitude is reflected by their exclusion from the society of the landed English families around them. When they had not left for the army or the church, the Huguenots were in small trades and education. Contrary to many hopes there were no weavers or silversmiths in the town.

Fine schools

The Huguenots did create however a reputation for fine schools, a number of which were offering the classics, French and ‘finishing’ activities by the 1780s. Unproven is the legend that the Duke of Wellington spent schooldays here and hated them. Feargus O’Connor, nephew of United Irishman Arthur O’Connor, and later Chartist revolutionary, tried to elope with his headmaster’s daughter, and Edward Carson too was sent to school in the town in the 1860s. Some though did not survive like ‘Walter Baker, jeune garçon a l’école de Mde. Bonafous’ who died in 1811. Some of the schools, now thoroughly anglicised, survived until the 1880s, by which time assimilation into the Irish way of life was virtually complete.

Unlike other continental Protestant groups the Huguenots of Portarlington never attempted a theocracy, a community of the good and godly. Where France was recreated in parts, it was the France of social and class divisions which was the paradigm. Two Huguenot names survive to this day, one of them having origins in the Alpine region of the Franco-Italian border. French festivals are held in Portarlington and it is La Douce France of Charles Trenet’s song, a touch of the Languedoc in Laois, and not religious wars, which is evoked, and why not?

John S. Powell works at York Minster Library.

Further reading:

J. S. Powell, Portarlington, Huguenots, Planters (York 1990).

S.J. Knox, Ireland’s Debt to the Huguenots (Dublin 1959).

C.E.J. Caldicott, H. Gough & J.P. Pittion (eds.), The Huguenots and Ireland: anatomy of an emigration (Dun Laoghaire 1987).

R. Vigne, ‘“Le Project d’Irlande”: Huguenot migration in the 1690s’ in History Ireland (Summer 1994).