How the Central Powers were defeated, July–November 1918

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2018), Volume 26, World War IBy high summer of 1918, German forces on the Western Front had been fought to a standstill. Having expended their reserves in a series of offensives collectively known as the Kaiserschlacht (‘Kaiser’s Battle’), the high command of the German Army nervously awaited the inevitable Allied counterstrokes.

By Mark Phelan

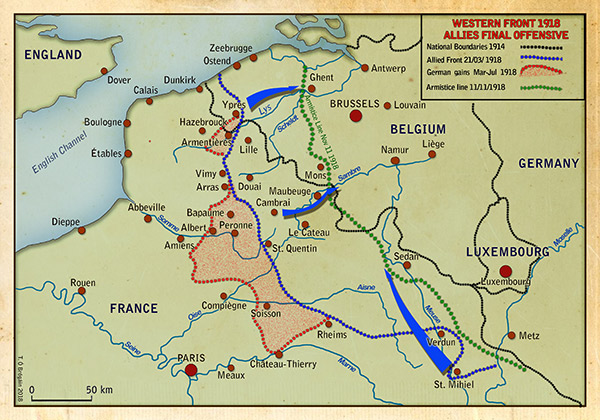

The Second Battle of the Marne (15 July–6 August 1918), which saw French arms, supported by British, American and Italian troops, repeat the feat of 1914 by turning back Germany’s best divisions within 100 miles of Paris, marked the irreversible turning of the tide in the western theatre. While each side suffered c. 130,000 casualties at the Marne, the cost bore heaviest on the exhausted Germans. Fed on promises of victory in the spring, the rank and file now succumbed to a fatalism mirrored by the German home front. Hopes of achieving a compromise peace sustained Germany’s leadership nonetheless, but the outcome of the Battle of Amiens (8–11 August 1918) cast a shadow over this prospect also. Innovative tactics defined the Amiens operation, which British Empire troops spearheaded. Learning from the costly attrition battles synonymous with the Somme (1916) and Passchendaele (1917), the attackers eschewed a preliminary bombardment, opting instead for a zero-hour ‘creeping’ barrage that kept pace with the first-wave assault. In addition, more than 500 tanks—a decisive weapon that the Germans neglected to develop—broke the enemy lines, neutralising wire obstacles and machine-gun positions. Local air superiority also played a key role, as did neat squad tactics on the part of well-drilled Australian and Canadian infantry. The ‘combined arms’ premise of the operation paid spectacular dividends, with the British and Dominion battalions punching a fifteen-mile gap in the German lines, and capturing more than 16,000 troops on the opening day of the offensive.

The Grand Offensive

Above: General Eric Ludendorff—notoriously described 8 August 1918 as ‘the black day of the German army’.

The end-game involved a three-pronged assault that exploited the Allies’ advantages in terms of manpower and matériel. Foch understood that committing his forces piecemeal would suit the weaker Germans: still in possession of excellent lateral railways, the enemy could fire-fight effectively by redistributing forces to and from critical sectors as these arose. To guard against this, Foch and his Anglo-American peers plotted simultaneous campaigns that would methodically destroy the understrength German field armies.

On 28 September 1918, the Groupe d’Armées des Flandres (GAF) drove north and east along the Belgian coastline. Incorporating six French, twelve Belgian and ten British divisions (including the 36th Ulster Division), this force overwhelmed the Germans in front of Ypres before grinding out victories at Ostend, Bruges and Courtrai. Although the GAF failed to reach its primary objective of Antwerp, it did tie down major German reserves and ultimately reached the Belgian–Dutch border in late October.

Further south, the same British and Dominion forces that had triumphed at Amiens smashed the much-feared Hindenburg Line. Once again Canadian and Australian units featured prominently, attacking fortified positions at the Canal du Nord and the St Quentin Canal respectively. As the centre-piece of the Grand Offensive, the assault on the Hindenburg Line commenced on 29 September, and by 10 October the strategically important town of Cambrai had fallen. The rapid capture of Cambrai reinforced the Allied belief that demoralisation now gripped the German rank and file. Even so, occasionally fierce German resistance meant that the British paid a high price during the subsequent pursuit to the rivers Selle and Sambre. In fact, before German discipline finally gave way in early November, total BEF casualties incurred from August 1918 surpassed 300,000. This sobering figure included the talented poet Wilfred Owen, who died at the Sambre–Oise Canal on 4 November.

A joint Franco-American assault formed the southern wing of the Grand Offensive. Advancing toward Sedan across the scarred Verdun terrain, French and American forces became stalled in the Argonne forest. Involving 22 US divisions, the battle for the Argonne became the largest enterprise undertaken by the Americans during the war. A combination of inexperience, poor leadership and almost suicidal bravado ensured that it was also the costliest: by the time the woodlands had been cleared in late October, US casualties exceeded 120,000, including some 26,000 men killed in action. Sedan itself remained in German hands until 6 November, when French forces retook the city and its vital rail-hub.

Breakup of the Central Powers

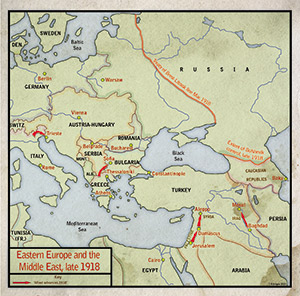

The critical situation on the Western Front demoralised Germany’s international partners. In rapid succession, Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary all sued for peace in autumn 1918. The war-weary Bulgarians faced a multinational army representing Serbia, France, Britain and Greece. Striking north from fixed positions on the Macedonia front in mid-September, coalition forces soon reached open country and forced the Bulgarians back on Sofia. Mutiny gripped the retreating army, which in turn sparked civil unrest in the capital. As royalist and republican forces battled for control, Bulgarian plenipotentiaries hurried to the Allied HQ in Thessalonica, where an armistice was agreed with effect from 29 September 1918.

The critical situation on the Western Front demoralised Germany’s international partners. In rapid succession, Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary all sued for peace in autumn 1918. The war-weary Bulgarians faced a multinational army representing Serbia, France, Britain and Greece. Striking north from fixed positions on the Macedonia front in mid-September, coalition forces soon reached open country and forced the Bulgarians back on Sofia. Mutiny gripped the retreating army, which in turn sparked civil unrest in the capital. As royalist and republican forces battled for control, Bulgarian plenipotentiaries hurried to the Allied HQ in Thessalonica, where an armistice was agreed with effect from 29 September 1918.

Crucially, Bulgaria’s defeat closed the intersection that linked Germany and Austria-Hungary to the Ottoman Empire. Panic now broke out in Constantinople, which had been left exposed by the folly of Turkish grand strategy. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution had created a power vacuum in the oil-rich Caucasus, which the Turks rushed to exploit. In so doing, however, they overextended themselves, and had insufficient troops available to shield Constantinople from the consequences of Bulgaria’s surrender. Equally, the Ottomans’ commitment to the Russian borderlands had denuded their garrisons in Transjordan. In this theatre British regulars, supported by Hashemite guerrillas under the stewardship of the celebrated Capt. T.E. Lawrence (‘Lawrence of Arabia’), captured Aleppo and Damascus with relative ease. These combined crises put paid to the unpopular dictatorship of the ‘Three Pashas’ and precipitated the harsh Peace of Mudros (30 October), which enabled the Allies to occupy Constantinople and begin the partitioning of Anatolia.

Turkey’s surrender narrowly anticipated the breakup of Austria-Hungary. From the outset of the war, the complexities of the Habsburg Empire had undermined its military performance. Severe casualties, blockade and a general political awakening impelled by the Russian revolutions and the much-heralded peace plan of US President Woodrow Wilson (the so-called ‘Fourteen Points’) stoked pre-existing tensions that revolved around class and national divisions. Disillusioned with the German alliance, Austria-Hungary unsurprisingly sought a way out of the war, even before the commencement of the Grand Offensive. Negotiations with Wilson’s emissaries progressed slowly, however, and were eventually overtaken by the Battle of Vittorio Veneto (24 October–2 November 1918). Breaking though across a wide front, rampant Italian divisions advanced on Trieste, prompting c. 300,000 Habsburg troops to surrender in short order. This crushing defeat resulted in the armistice of Villa Giusti (3 November 1918) and the formal breakup of the imperial Austro-Hungarian state, which was swept aside by popular insurgencies in Poland, Bohemia and the Balkans.

German peace feelers

Against this backdrop of international isolation and pending military collapse, Germany’s leaders frantically considered their options. On 28 September 1918, Ludendorff secretly conceded that the war was lost and called for an armistice on the basis of the aforementioned ‘Fourteen Points’. Of course, Ludendorff and the high command, who ruled Germany as a military dictatorship from 1916, did not want to be tarnished by the reality of military defeat. Conscious of the verdict of history, the generals thus decided to pass responsibility to the hitherto-toothless German parliament. Incidentally, the ulterior thinking of the military élite dovetailed with parallel plans hatching in the German Foreign Office. Paul von Hintze, who had a clear grasp of the competing war aims of Germany’s transatlantic enemies, then served as foreign minister. Hintze wished to pursue an ‘American peace’ in order to forestall the harsh terms that France and Britain could be expected to impose. Accordingly, Hintze lobbied for Germany to transition to a constitutional monarchy, even before Ludendorff confided that the army was beaten. Consulting independently of the Kaiser, both men accepted that Germany must embrace the optics of democracy in order to appeal to US opinion. Equally, both men feared the potential for a German sequel to the Bolshevik coup of 1917, and preferred to risk revolution ‘from above’ rather than passively await a more volatile revolution ‘from below’.

In early October 1918, therefore, the German parliament assumed greater powers, which enticed democratic socialists, Catholic centrists and other moderates into government. In turn, the changing of the guard triggered diplomatic exchanges between Berlin and Washington. Although these contacts highlighted the crisis atmosphere in the German capital, they did not produce the damage-limitation outcome that Ludendorff and Hintze hoped for. German diplomats negotiated in the belief that tensions between the US and its European partners could yield a favourable peace. In particular, they hoped to preserve the German military, which could provide leverage during the post-armistice negotiations and scotch any putative communist uprising. This calculation backfired, however. If anything, the peace feelers pushed Wilson, Clemenceau and Lloyd George closer together, with the ‘Big Three’ accepting the advice of their generals, who wanted to maintain the Grand Offensive until it broke German resistance completely. At the same time, the public appeal for peace undermined the coherence of German arms, accelerated the collapse of Germany’s partner powers and hastened the dreaded revolution, which overtook the diplomatic process in early November 1918.

November revolution and armistice

Above: The Allied high command—Pétain, Haig, Foch and Pershing. (Alamy)

By then, special envoys had also reached the French town of Compiègne, where they formalised Germany’s surrender by signing cease-fire terms that came into effect at 11.00 hours on 11 November 1918 (the much-quoted ‘eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month’). In the event, Germany accepted whatever conditions the Allies felt pleased to present. These included ceding the Rhineland to temporary Allied occupation, the internment of the German High Seas Fleet, the hand-over of hundreds of warplanes and the continuation of the naval blockade that had strangled the Central Powers from 1914. This humiliation meant that Germany was unable to resist the controversial peace subsequently imposed at Versailles in 1919, while it also provided context for the notorious ‘stab in the back’ thesis. According to this dangerous myth, the German army emerged from the war undefeated, only for Jews, Bolsheviks and other anti-national elements in Berlin to betray the fighting men. Chief exponents of this distortion included Ludendorff and Adolf Hitler, who marched shoulder to shoulder at the head of the abortive 1923 ‘Beer Hall Putsch’ that first brought the future dictator to international attention. Twenty years later, at the turning point of the Second World War, Nazi adherence to the fiction of a 1918 ‘betrayal’ justified the policy agreed by Churchill and Roosevelt at the Casablanca Conference. Determined that German nationalists should have no further opportunity to falsify history, the heads of the revived Allied coalition backed the ‘unconditional surrender’ policy that culminated in the unequivocal defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945.

Mark Phelan lectures in twentieth-century Irish and European history at NUI Galway.

FURTHER READING

N. Lloyd, Hundred days: the campaign that ended World War I (London, 2013).

D. Stevenson, 1914–1918: the history of the First World War (London, 2005).

T. Travers, How the war was won: command and technology in the British Army on the Western Front, 1917–18 (London & New York, 1992).